Orgreave: The battle that's not over

- Published

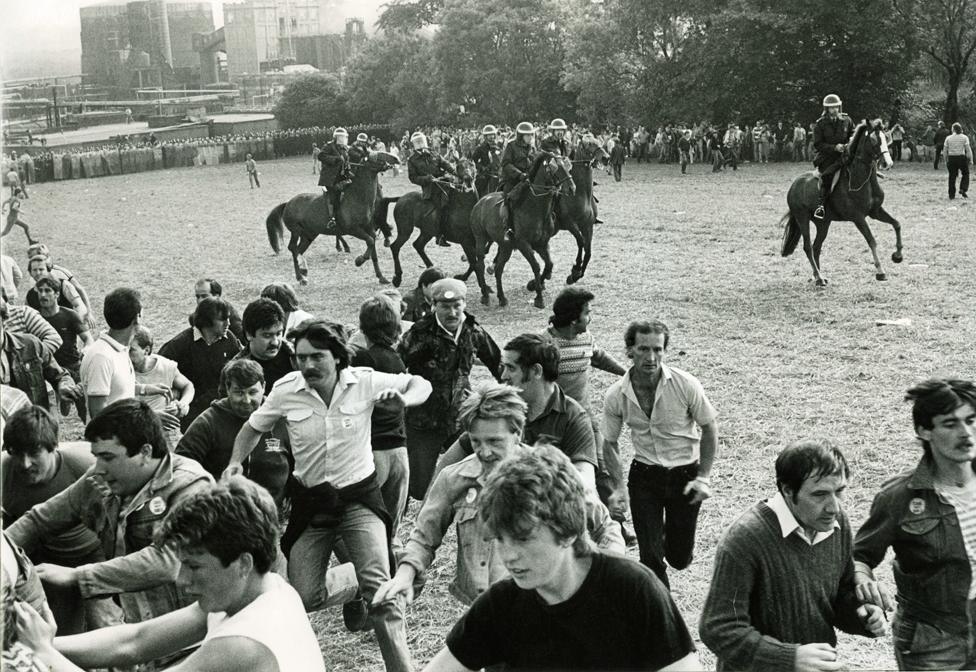

In 1984 police and striking miners clashed violently at Orgreave in South Yorkshire. But now there is growing pressure for an inquiry to investigate what went on that day.

Orgreave is an ugly word. Stubbornly linked with one of the most violent episodes in British industrial history.

Even the developers transforming the place are trying to change it. "We are Waverley," declare the signs. "A vibrant new community providing leading-edge jobs and desirable new homes."

It's a place Stefan Wysocki will never forget and yet he's struggling to recognise it.

Former miner Stefan Wysocki alleges police brutality at Orgreave in 1984

This is the first time he's been back in 32 years and a lot has changed. "Ah," says the retired miner in a gruff north Midlands accent, "that's where I got arrested, just in front of that bungalow there. I'd been chased up the field and over this bridge by the police. I needed to sit down and get my breath back. Then I heard one of them say, 'Get that big bastard there with the white shirt on'."

Stefan's fingers tremble as he describes his arrest. The police officer was right about Stefan's size. He is stocky, taller than most miners. He walks with a limp after a roof collapsed underground crushing his foot. He's used to hard work and the hard knocks of a dangerous industry with a macho culture.

But Orgreave's not an easy place to return to; the memories aren't pleasant to recall. "They marched me back down the hill to the line of police officers with shields and bounced me off them. The line opened up and they knocked ten bells of crap out of me. I was punched and kicked… I walked in and I was carried out."

The Battle Of Orgreave

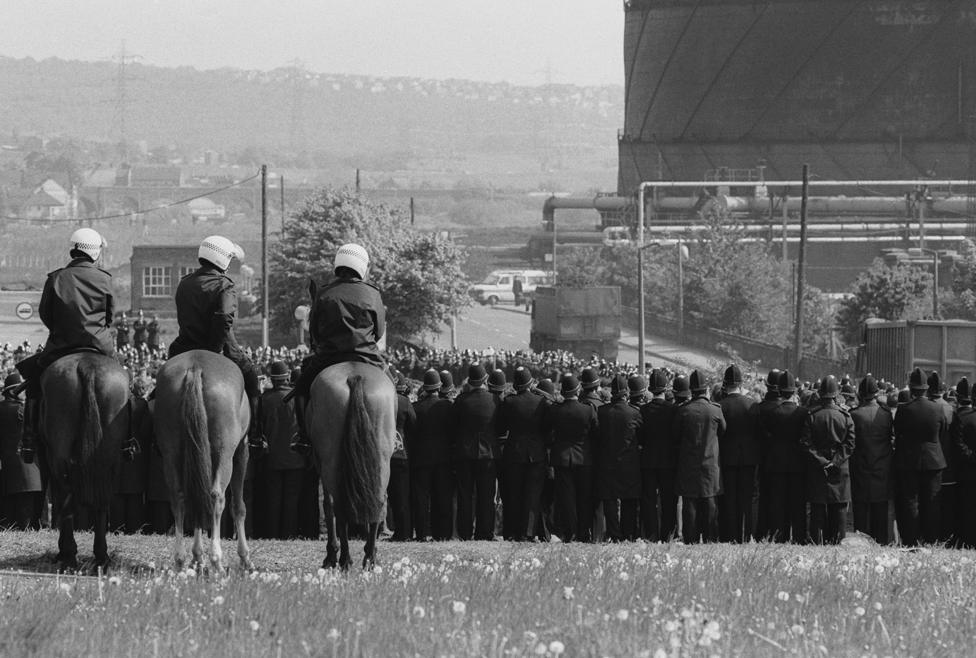

He was one of thousands who flocked to Orgreave on that hot summer Monday - 18 June 1984, three months into the dispute. The striking miners wanted to stop lorries carrying coke to fuel the Scunthorpe steel furnaces. They thought disrupting production would help win their fight against pit closures and job losses.

The day was to become one of the pivotal moments of the year-long strike, a bloody battle that saw nearly a hundred miners arrested and even more injuries between police and pickets. At stake for the miners was the future of their industry, and livelihoods built on coal. The government saw a threat to law and order that the police had to resist.

As usual, there had been a "push", the miners pressing up against the police shields. But Stefan is firm in his view that the decision to charge at the crowd with horses and truncheons was over the top, and even showed a deliberate attempt to give a clear message that the miners would not succeed.

Stefan admits stones were thrown at the lines of police officers in riot gear who'd been bussed in from around the country. He's adamant he never threw anything but the police said he did.

Paul was one of those told to charge - a young police constable from Merseyside called into South Yorkshire to bolster the numbers. Paul isn't his real name. He too finds it difficult to talk about Orgreave and fears the consequences of speaking out. But he is prepared to give evidence if there is any inquiry.

His unit was on duty at 05:00 to make sure the lorries could leave. He was among 6,000 officers along with police horses and dogs. But Paul claims their orders - which came from senior South Yorkshire Police officers - went much further.

"They anticipated a lot of trouble," he says. "They told us if there was any trouble at all we needed to stamp it out straight away and use as much force as possible."

Paul had policed other picket lines during the strike but says Orgreave felt different. "[South Yorkshire Police] were anticipating trouble and in some ways relishing it and looking forward to it. It was a licence to do what we wanted which I didn't think was right because we didn't know what was going to happen."

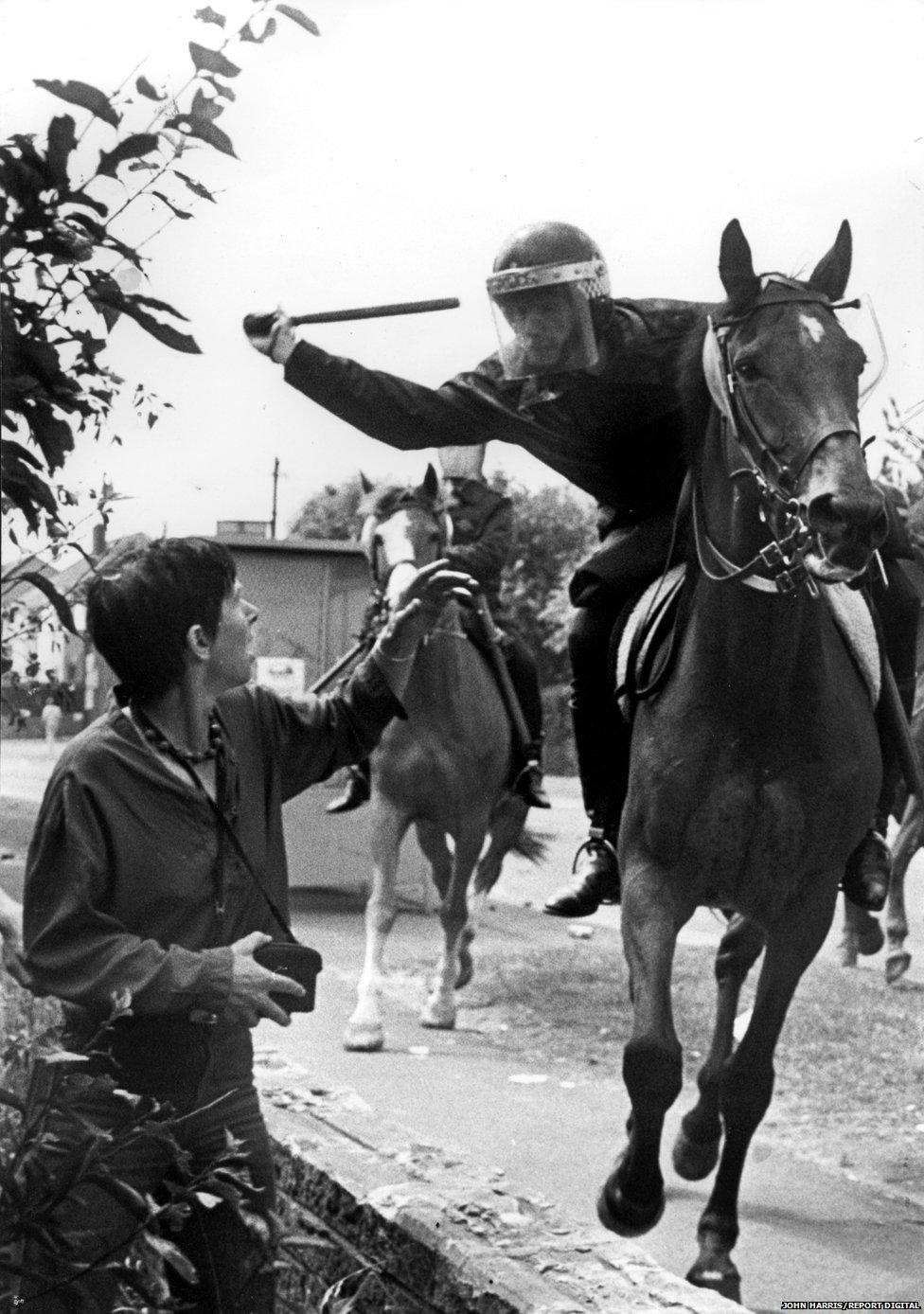

When the order came to draw their truncheons and charge at the crowd of miners, Paul and a few of his colleagues were uneasy.

"Some of us stood saying 'they're actually doing nothing here' so a few of us held our line and then officers with short shields came from behind and just charged these miners who were virtually doing nothing.

"And the next thing is there were running battles and miners were falling over and police officers were batoning them."

It was the first time police in the UK used "short shield" tactics. Previously they stood behind long, tall shields, defensively holding a line.

Now instead, officers with small, round shields and truncheons drawn went on the offensive, breaking up the crowd and making arrests.

On the video the police themselves recorded, a senior officer is heard giving instructions to use force: "No heads, bodies only." That was an order to incapacitate but not seriously injure - an order that didn't reach everyone.

There were injuries on both sides but more miners needed treatment. There was shock at the level of violence captured in TV pictures - police officers and pickets in hand to hand fighting. One miner was hit so hard the officer broke his truncheon.

Exactly what happened has been argued over for a generation. The BBC's television report on the evening news that night was criticised by the miners and their supporters for giving a misleading impression. The assistant director general conceded later that some coverage "might not have been wholly impartial".

But the key question in the lasting dispute of Orgreave is who was responsible for escalating the violence?

The police say they were being hit by rocks and bottles and had to react to protect themselves. The miners say they were peacefully protesting when the police charged and attacked them. And it's not just brutality the police stand accused of.

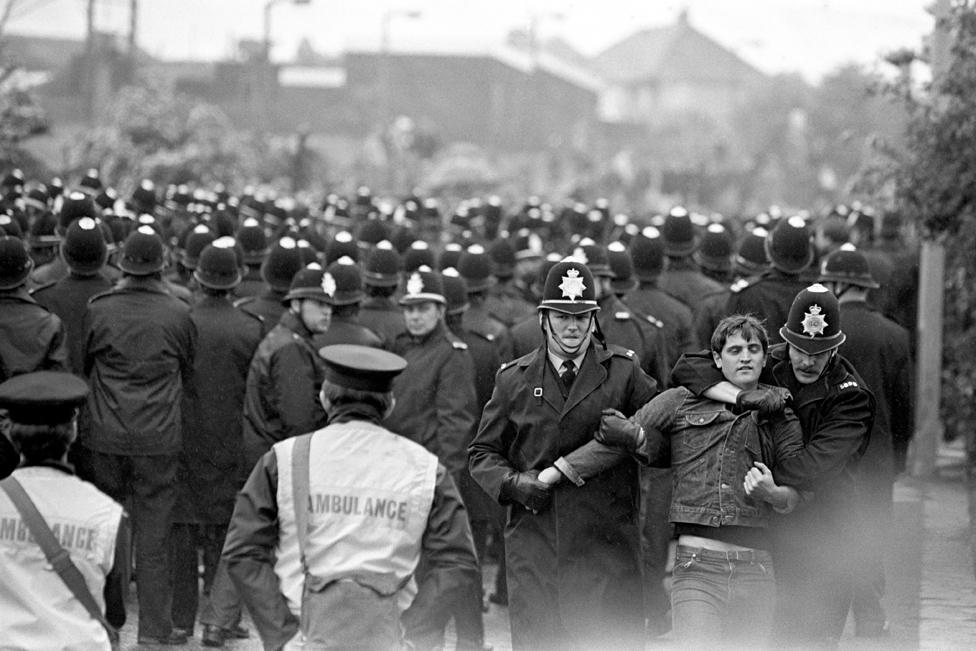

Miners who'd been arrested - 95 of them - were taken to an old office block opposite the coking works that served as the police command centre. Prisoners were processed before being taken to a police station and eventually put before magistrates. Their details were noted and their photograph was taken with the officers who had arrested them.

An injured policeman is led to safety

Some of those officers have described how they went upstairs to a room - like a school classroom - with desks where they could write their statements, a formal account of why they'd made the arrest.

But many of those officers had come from across the country in the dark in the early hours of the morning. They didn't really know where they were. They'd lost track of time and didn't know the local road names - the sorts of details that would be needed.

They didn't have to worry - a team of South Yorkshire Police detectives was on hand to help. But it's alleged that what happened in that classroom went far beyond assistance with times and place names.

South Yorkshire Police has been accused of dictating chunks of statements in a co-ordinated attempt to prove the arrested miners were guilty of more serious offences.

Four years ago the BBC got hold of hundreds of police statements that had been mouldering away in a garage.

They revealed that dozens of officers - from different police forces, involved in separate arrests - had written the same phrases, again and again, virtually word-for-word.

The suggestion is that by controlling the narrative and exaggerating the extent of the violence from the miners, the police could provide evidence of more serious offences, evidence that could mean longer prison sentences.

Soon after this was broadcast in 2012, South Yorkshire Police referred the matter to the Independent Police Complaints Commission. Around the same time a group of ex-miners and their supporters got together to call for a public inquiry into the actions of the police - the Orgreave Truth & Justice Campaign was born.

Documents released since then reveal that the officers who oversaw the gathering of statements were detectives from South Yorkshire's Serious Crime Squad.

The team was led by Detective Inspector Derek Smith. Working with him on 18 June 1984 was Detective Sergeant Glynn Connor and Detective Constables John Hudson, Keith McSloy and Stephen Wyatt. Their names appear as witnesses on dozens of police statements.

Derek Smith's own statement lays out how the operation was run. "Our duties consisted of collating evidence relating to demonstrators arrested at that location."

But things changed. "From the first person arrested it was utter chaos due to the volume of police officers involved. I established from them what had taken place and instructed them that I would dictate the opening paragraphs of their statements, which would contain their location and an agreed account of what had taken place generally."

Mr Smith notes in his statement that he couldn't see the demonstrators or the front line officers from the command post. He made it "clear that if there was anything they (the arresting officers) disagreed with they must make their statements accordingly".

When he was approached recently he said officers from other forces weren't under his command therefore he had no control over what they wrote in their statements.

Mr Smith told the BBC his team didn't deal with arrests by any South Yorkshire officers, even though some of the statements suggest they did.

Some officers, including South Yorkshire constables, named Smith and members of his team when they were asked in court about their statement being dictated.

Mr Wyatt denied any collusion over the statements. He said: "I am keen to answer any questions that [an] inquiry may ask of me but, in that context, I feel it would be inappropriate at this time for me to comment further."

Mr Smith said: "Arrests were made by officers from other forces who had their own chain of command. Neither I nor my officers had any control over them or the contents of their statements of evidence."

Mr McSloy said: "I will be more than willing to answer any questions, asked by yourselves or a review panel, to the best of my ability at the appropriate time." But he added he could not comment before any review.

The other two former detectives approached for comment did not respond to the request.

Mr Smith and his officers were following the orders of the Chief Constable of South Yorkshire, Peter Wright. He'd come to the job from Merseyside where as deputy chief constable he'd been in command during the Toxteth riots of 1981. Many of his former officers were in the police lines at Orgreave. After the strike, Wright explained the evidence gathering operation to the Police Committee, the group of local councillors overseeing his force.

The confrontation at Orgreave didn't come out of the blue. Picketing miners had been gathering there in growing numbers through May and June of 1984. The level of violence had been increasing too.

The Sun's front page headline on 30 May was "Charge: Mounties rout miners".

The chief constable decided that instead of the usual charge of disorderly conduct more serious charges of unlawful assembly and riot would be pressed, according to a document from September 1985.

A chief superintendent was appointed to "organise the collection and collation of evidence". It was this chief superintendent who oversaw Smith and his team.

Ninety-five miners from Orgreave were charged with unlawful assembly or riot. Stefan Wysocki faced a riot conviction which could have meant 25 years in prison.

The case took almost a year to come to court. "It was a horrendous year and it was horrendous in court," he says.

For 48 days the miners listened to the evidence that could put them behind bars. But cracks started appearing in the accounts of the police officers.

A miner accused of throwing a stone had actually been photographed holding a pork pie. Officers who claimed to be in certain locations at specific times were proven to be elsewhere. Some admitted to the court that parts of their statements had been dictated by detectives.

Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher with Leon Brittan, the home secretary at the time of Orgreave

One officer was questioned about the signature of the colleague who had witnessed his statement.

It didn't look like the signature on the constable's own statement. He denied forging it and one of the defence barristers asked for the opinion of a handwriting expert.

During the break for lunch the statement inexplicably disappeared from the courtroom - "a most extraordinary thing", noted the judge.

There was, however, a photocopy which was sent for analysis. When the expert's report came back the prosecution suddenly and dramatically dropped the case against the miner arrested by those two officers.

Within 10 days, the whole trial had collapsed and the other miners awaiting a court date were told they had no case to answer. It was an embarrassing climb-down.

There were celebrations among the miners, and questions about the conduct of the police. But there's no evidence anyone was disciplined or held to account.

Government papers released last month show the Home Secretary Leon Brittan and the Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher discussed speeding up prosecutions and giving greater publicity to convictions and sentences.

The then home secretary made it clear to the South Yorkshire Police Authority that proposals to phase out police horses and dogs were unacceptable.

"I think it was all set up from start to finish. I think Mrs Thatcher wanted to prove a point," says Stefan Wysocki. "She wanted it to end her way, to put us down and make us look like thugs. But we weren't. To be treated like that - it was disgusting. It's still disgusting."

Orgreave today - a housing estate now stands where the coke plant once stood

Lord Tebbit was secretary of state for trade and industry at the time - he was present at many of the top level meetings involving the prime minister and home secretary - and he believed the action taken to stop pickets blocking a plant was entirely reasonable.

"The British police is not some sort of stormtrooper group like Hitler's National Socialist German Workers Party or anything like that. They were there to preserve the peace. Had the pickets obeyed the law all would have been well. They chose to use physical force to try to stop men going back and forth on their legitimate path to work so the police had no option but to prevent that from happening."

Orgreave stands as a turning point in the miners' strike, in policing tactics and industrial relations. There was no more mass picketing there after 18 June.

Within weeks the first miners began returning to work. Though many clung on until March 1985, ultimately they were beaten. Many would argue it showed once mighty trade unions had been weakened, as state owned industries were privatised. Kellingley Colliery, Britain's last deep coal mine, closed at the end of last year.

The Independent Police Complaints Commission spent almost three years weighing up the evidence. In 2015, it concluded there were issues worthy of investigation but it wasn't in the public interest.

The miners' strike 1984-85

Thoresby mine during the 1984 miners' strike - it closed in July this year

Year-long industrial action by National Union of Mineworkers, led by Arthur Scargill, in protest at Conservative plans to close 20 pits, with the lay-off of 20,000 workers

The biggest strike in the post-war era (at its height, 142,000 mineworkers were involved), it was also one of the bitterest industrial disputes in British history

The strike ended on 3 March 1985 with the NUM having failed to achieve concessions from the government

South Yorkshire Police would not address the specific points that have now been raised, saying it is mindful of a possible review. But the force says it is "acutely aware of the impact such long-standing unanswered questions can have". It has vowed to participate fully in any inquiry.

It is the current Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, who must now decide what happens. She has promised an announcement before the end of October. There are voices urging her to resist launching an inquiry, like Lord Tebbit.

"It would be a waste of time and of money. The facts are absolutely clear, they are well-known. We don't need to rehearse it at great benefit to the legal profession who will make millions out of it - to what end? These are events of 30 years ago, the facts are known."

But for many the facts are still to emerge. There is a relentless rumble of unease about Orgreave, from those who say they're still waiting for the truth.

Additional reporting by Dominic Hurst

Join the conversation - find us on Facebook, external, Instagram, external, Snapchat , externaland Twitter, external.

All images subject to copyright