The myth of the mob: How crowds really work

- Published

Is our growing understanding of the psychology of crowds feeding in to how we police them?

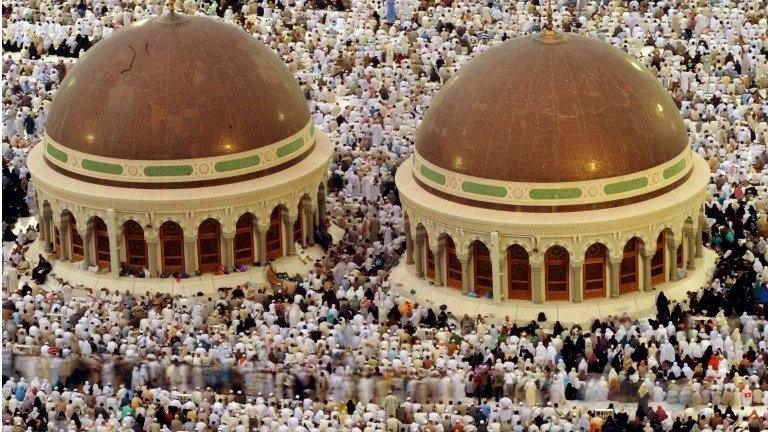

Crowds are complex. Some people fear they may turn violent, with individual personalities becoming submerged in the group mentality.

But some leading social psychologists who research crowds believe that this old picture is mistaken.

"The danger with this view of crowds as inherently violent isn't just that it's wrong, it's that it might become true. It might lead us to treat crowds in ways that will enrage them," says psychologist Professor Steve Reicher.

Of course crowds are not all the same - there are different types of crowd and controlling them requires different approaches.

The violent crowd

There are violent crowds, of course. Some sporting crowds become violent. For example, British football stadiums in the 1970s and 1980s became notorious as arenas for hooliganism between rival sets of fans.

There were tense and sometimes violent clashes in Ferguson after the police shot an unarmed 18-year-old man in August 2014

Political rallies can also become violent, although they often begin peacefully enough. Then there are spontaneous riots, usually sparked by a particular incident such as a police killing. Unrest in the St Louis suburb of Ferguson in the American mid-West in August 2014 began after the fatal police shooting of Michael Brown.

In Britain, in August 2011, a police killing of Mark Duggan in north London set off a wave of violence across the nation. Even when there are outbreaks of violence, the targets are not random: in that sense, it's an error to regard them as crazy, or without reason.

The benign crowd

Despite the popular conception of the dangerous crowd, Keele University's Clifford Stott also rejects the view that they are inherently threatening.

"The language of pathology that we use about the crowd, the idea that people become bestial in crowds, robs people of the meaningful nature of that behaviour," he argues.

Some crowds are remarkably non-violent even when baited. A good example is the civil rights movement in the United States in the 1950s and 1960s, where protestors usually remained calm in the face of provocation from the police. "Non-violence" was part of the movement's ideology.

In fact, not only are most crowds peaceful, but we positively seek them out, because we enjoy being among them. Watching a football match in a half-empty stadium is a dispiriting experience.

Much of the joy of being at a music festival is hearing the musical acts while surrounded by other devotees.

The 'non-crowd'

Of course, all this raises the question of what counts as a crowd.

Compare sitting at a crowded sports event with fellow enthusiasts and sitting in a train packed with commuters. The former is exhilarating, the latter can be uncomfortable.

Commuters crossing Tokyo's famous Shibuya crossing share no psychological connection

That is partly because there is no psychological connection between commuters - they don't feel any sense of shared identity. Now imagine that the train stutters to a halt in a tunnel and the driver announces on the tannoy that, because of a technical fault, there will be an indefinite delay. What will happen?

Well, people might begin to talk to each other and might even share their sandwiches. There is now a psychological connection between them, they are part of a group whose lives have been inconvenienced by the train company.

Having a sense of identity with others can influence us in myriad ways. Prof Reicher, from St Andrews University, ran a test involving sweaty T-shirts,, external the results of which were published earlier this year.

A group of 135 students were asked to smell the T-shirts. For one group, the shirt had a logo with which they could identify (that of their university). The other group had no connection with the shirt. They sniffed it for a shorter period and washed their hands with more soap afterwards.

The study authors inferred from this that the level of disgust was greater when there was no connection to the clothing.

On a packed train, we often find being squashed up against other human bodies repugnant, but not so when we are at a music festival.

Sense of identity

The study of crowds has many practical implications. One is how crowds should be policed. In the past, the British police have used a tactic which they call containment, but which is popularly known as kettling.

During a political demonstration, they may cordon off a crowd, preventing protestors from leaving for a period of time until it is deemed safe to disperse them. After a challenge, the practice was ruled lawful by the European Court of Human Rights.

Lawful, perhaps, but Prof Reicher believes it is a terrible way of dealing with the threat of disorder. When enclosed together, the sense of identity among the demonstrators becomes reinforced - just as it does with commuters stuck on a faulty train.

Former Met Police Commander Bob Broadhurst accepts 'kettling' has been used too crudely in the past

When demonstrators are kettled, they are forced to share the same fate which can forge a common identity. They may believe their legitimate rights have been trampled on and those within the group who advocate conflict with the police can become more influential.

It is often precisely those who had set out to express their legitimate grievances in a peaceful manner who can become most outraged by harsh policing.

"Every group has notions of right and wrong and it is always possible to enrage people by trampling on their notions of legitimacy," argues Prof Reicher.

"When there is kettling, the irony is that often the activists don't like it but they're used to it. It's people who've never experienced it before - and who suddenly find themselves being treated as if they're the sort of people their mothers warned them against - who are absolutely outraged."

The police often fear the influence of a few violent people, but by treating the crowd in an undifferentiated way, they risk magnifying the very influence they want to curb.

'Blunt tool'

Crowd psychologists like Prof Stott believe a better response is for the police to see their role as supporting lawful gatherings rather than impeding them.

"The best way to manage these problems is through facilitation of legitimate behaviour, not necessarily a focus on the control of illegitimate behaviour," he says.

There is some indication that the police are beginning to take the academic work on crowds seriously. For many years, retired commander Bob Broadhurst was responsible for public order in the Metropolitan Police.

Among many important public events, he oversaw the police operation during the G20 demonstrations in London in 2009, when demonstrators were kettled.

He still defends kettling as a legitimate tactic, but now concedes that "it was used as too much of a blunt tool".

During those G20 demonstrations, newspaper vendor Ian Tomlinson was struck by a police baton and later died. Since then, police forces up and down the country have deployed what are called Police Liaison Officers (PLOs).

Their job is not to arrest, but to talk and de-escalate tension when it emerges. Mr Broadhurst says that even when crowds are forcibly contained, lessons have been learned from past, often unpleasant experiences.

"You need to let the crowd know why you're doing it," he says. "And you need to target as best you can, those individuals who are the problem. The PLOs, by talking to protestors in the planning stage, are helping."

The evidence is beginning to pile up that this different approach to policing - not just at demonstrations, but at sports events too - would reduce violence, tension and police costs.

Good news for the police. And good news too for those who enjoy the thrill, the collective action and the sense of belonging that comes with being in the crowd.

David Edmonds presents Analysis: The Myth of Mobs on BBC Radio 4 on Monday at 20:30 BST. You can listen online or download the programme podcast.

- Published13 April 2016

- Published24 October 2013

- Published19 July 2012

- Published15 March 2012