Divisions persist about who should regulate UK press

- Published

The "recognition" of Impress means the UK finally has a press regulator that has signed up to all the standards laid out in the Leveson report.

The problem is that it represents only a tiny corner of the press. Impress has so far not had to deal with a single complaint.

Its membership is made up of smaller community papers, websites and hyper-local news operations, among them the Brixton Bugle, Shetland News and the Scottish investigative website, the Ferret.

Thorny issue of recognition

Three years on from the signing of the Royal Charter on self-regulation of the press, Britain's main newspapers are all still refusing to sign up to the Leveson system.

The principle that unites them all in their opposition is the belief that "recognition" is tantamount to "state regulation".

Ipso, which represents most of Britain's main national and regional newspapers (the Guardian, Financial Times and Independent all chose to go their own way) is not seeking recognition.

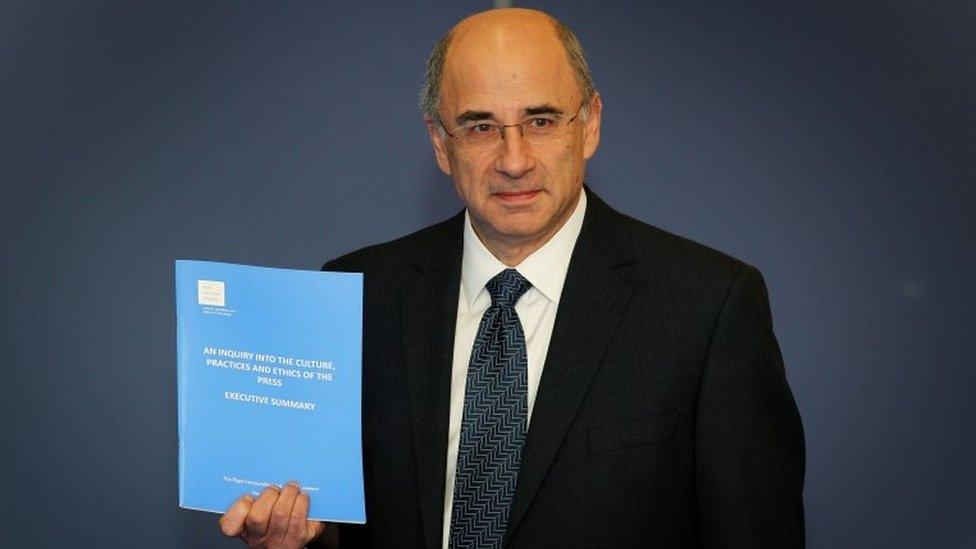

Lord Justice Leveson's report recommended self-regulation backed by legislation

That means that although Ipso says it has taken on board the recommendations of Lord Leveson, it is not interested in having an independent body, the Press Recognition Panel (PRP), check that it is actually complying with the 29 rules and standards laid out in the Leveson report.

The newspapers' argument is that the PRP is, despite its claims of being independent, an arm of the state.

Arbitration option

This was foreseen by Lord Leveson which is why there are legal incentives to encourage the press to sign up. The main stick to prod the papers is Section 40 of the 2013 Crime and Courts Act.

To understand it you have to look at one of the key recommendations of Lord Leveson - arbitration. Anyone who feels their reputation has been unfairly damaged by a newspaper article has at the moment only one legal route for compensation, the libel court.

For most people this is simply too expensive and too risky to contemplate. Arbitration is a low-cost and quicker alternative to going to the High Court.

Section 40 says if either newspaper or complainant refuses to take the option of arbitration they will have to pay costs in a High Court case even if they win. Britain's main newspaper owners have been resisting this being signed into law.

Culture Secretary Karen Bradley said she was in no rush to sign off Section 40

It has been passed by Parliament but is awaiting a final signature from Culture Secretary Karen Bradley. Facing questions from MPs, she said she has concerns about the effect it would have on newspapers but has not made up her mind.

Some newspapers are reporting they have been told privately she will not sign Section 40. However, even if she does not sign it remains on the statute book and if there is some future press scandal then it will be there as a possible option.

Newspaper opposition to Section 40 is focussed on the fear that if they do not offer an approved arbitration scheme they could face libel claims in which claimants face no risk of paying costs.

The economics of news are tough at the moment - this looks like a catastrophic extra financial risk for anyone who wants to resist signing up to a "recognised" regulator.

Insurance for investigations?

So why have Impress's members signed up to such a system? The answer is the rarely discussed "carrot". Section 40 works two ways.

If a rich and powerful individual or organisation threatens a journalist with a libel writ then arbitration offers a low-cost escape route from a ruinously expensive court case.

The highest settlement in Impress's scheme is £3,000. High Court actions usually cost £150,000 at a minimum. If that individual ignores arbitration and presses on with a libel action then the High Court can force them to pay costs even if they win.

Arbitration offers a new insurance policy for investigative journalism and for websites and news organisations wanting to do stories about people with expensive lawyers. This is one reason why websites such as Byline and the Ferret have signed up to Impress.

Libel cases against English newspapers are heard at the High Court

Had arbitration existed in the past perhaps parts of the press would have had a little more nerve with stories about highly litigious individuals such as Robert Maxwell and Jimmy Savile.

However, there is also a wider point in all of this. The argument about "state regulation" and a "free press" is not as clear as it might appear.

The Royal Charter system of press regulation is still self-regulation. Ipso is funded and overseen by the newspapers. Impress is funded by a mix of charitable trusts and foundations.

Among the donors to those funders are the former boss of Formula 1, Max Mosley, and JK Rowling, neither of whom has a say over any decision-making process.

Newspapers' fears

The Press Recognition Panel is independently appointed and would merely give self-regulation a warrant of approval that it was meeting the Leveson standards.

However, large parts of the British media are regulated by an arm of the state. Sky News, ITV, TalkSport, the BBC amongst many others are all subject to regulation by Ofcom.

However, only TV and radio broadcasts are subject to their rules for accuracy and impartiality. Articles on their websites are not included.

If you want to complain that an online video by a broadcaster is not accurate or fair then it would depend if it was on a media player, TV or a website.

It is complicated and far from clear to the public. It is not even clear yet whether the BBC News website will be subject to Ofcom regulation when the BBC Trust is replaced next year.

The old dividing lines between broadcast and print and who regulates what is breaking down. Ipso will take complaints about videos on news websites, Ofcom will not.

So, in conclusion, the "recognition" of Impress does not change much. However, if Section 40 were to be signed then the presence of Impress, an approved regulator, would change everything for Ipso.

The editorials and campaigning by the newspapers reflect a real fear that a single signature could make it almost impossible to continue to resist press regulation as envisaged by Lord Leveson.

- Published25 October 2016