What the Farage ambassador row could mean for UK-US relations

- Published

At Number 3100 Massachusetts Avenue in Washington, high enough up the hill to catch a breeze in this most airless of cities, lies a small corner of a foreign field that in theory is forever England.

For it is here that one finds the British embassy and one of the finest ambassador's residences in the world.

To walk through the marbled grandeur of this, the only building designed by Sir Edwin Lutyens in North America, is to understand how architecture can itself be an act of diplomacy.

And if you stroll through the grounds and inspect the fine collection of orchids, and ignore the car horns and springy tropical grass, you can imagine yourself in a rather grand English garden.

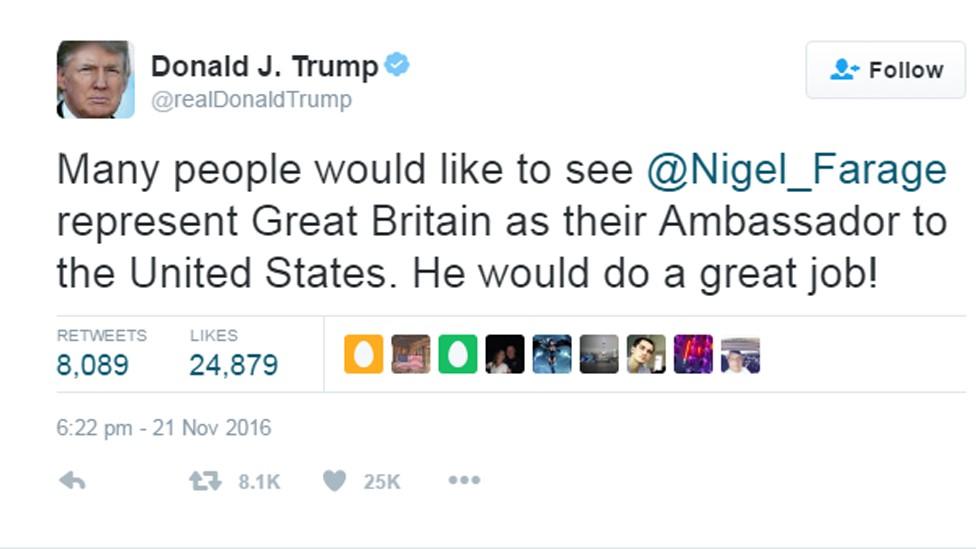

It is here, Donald Trump has said, that many people would like UKIP's interim leader, Nigel Farage, to live and work.

The sheer chutzpah and breach of diplomatic protocol in a future head of state telling the Queen whom she should appoint as her ambassador to the United States has understandably raised hackles across Whitehall.

But before we work ourselves into too much of a lather of indignation, we should be aware that there is a precedent for this.

It is widely understood that President John F Kennedy suggested to Harold Macmillan in 1961 that he might like to appoint the Conservative politician Sir David Ormsby-Gore as Britain's ambassador.

They had met and become friends when JFK's father was ambassador to London.

John F Kennedy wanted Sir David Ormsby-Gore to be the UK ambassador during his presidency

As The Chicago Tribune reported on 18 December 1967, "[Ormsby-Gore] was among the first persons to be invited to lunch by the president-elect, and their meeting in the Carlyle Hotel in New York City was portentous.

"In fact, Jack Kennedy handpicked his old friend, though the British would never admit it.

"David's position as ambassador was doubtless discussed at the Carlyle lunch. And later when Prime Minister Macmillan brought up Ormsby-Gore's name, Kennedy leapt at the chance to say how pleased he would be by the appointment."

Of course, that appointment was based on personal, family links, not political endorsement.

So close were the families that Kennedy arranged for Ormsby-Gore and his wife and children to be given a place in the presidential nuclear bunker.

But the point stands: the president expressed a preference and the UK government acquiesced, albeit for very good reasons as Ormsby-Gore was a closer adviser to Kennedy than many of his cabinet.

Even in normal times, the White House would have a say over our man in Washington.

The Foreign Office recommends a candidate to the Palace, a name that has been signed off by Number 10.

The Queen agrees, Washington is informed, and the government then seeks formal consent.

So in theory, Mr Trump could veto the appointment.

But it very rarely happens.

And, whisper it quietly, there is occasionally the odd sounding taken.

One former diplomat told me: "Normal procedure is that the government chooses someone as ambassador and then privately proposes the name to the host country, which has to agree.

"It is all done privately.

"And it is very rare for a candidate to be turned down, in my experience."

But all this is a world away from the US actually suggesting a nominee, as Mr Trump has just done.

Much of the reaction I have heard from diplomats is not printable.

"Truly bizarre" is perhaps the least expletive-ridden summary I can give you.

As a class, British diplomats oppose political appointees, because they take top jobs from the professionals.

They did not like James Callaghan appointing his journalist son-in-law, Peter Jay, as ambassador in Washington.

And they tolerated David Cameron sending his chief of staff, Ed Llewellyn, to Paris only because he had a past life as a de facto diplomat in Hong Kong and Bosnia.

But their real concern is that this Twitter diplomacy might endanger UK-US relations.

The government, they say, will have no alternative but to reject the Trump suggestion.

The UK embassy in Washington plays a key role in maintaining UK-US relations, as with this meeting between Gordon Brown and Barack Obama

One former senior diplomat said: "A Farage appointment would be completely unacceptable to British cabinet ministers, including the foreign secretary, who would have a vainglorious and uncontrollable political opponent as their envoy to the president."

In many ways, the Trump suggestion makes the current ambassador, Sir Kim Darroch, even safer in his job.

Sir Kim is highly rated but has taken some flak for failing, along with everyone else, to predict the Trump victory.

But if Theresa May chose to replace him - he was of course appointed by her predecessor whom he served as national security adviser - she would face accusations of doing Mr Trump's bidding.

She cannot be seen to capitulate.

The real difficultly, say diplomats, is that it appears to show that the Trump administration thinks that diplomacy is a bit of a laugh, something for a fun Twitter exchange rather than serious business.

Nigel Farage backed Donald Trump throughout his presidential campaign

Only a day after Downing Street confirmed it was exploring offering a state visit to Mr Trump next year, he responds by pushing the UK into public disagreement.

"My wider and bigger concern is how we are going to manage our diplomacy with US and Europe," one former FCO official said.

"This sort of thing makes it harder."

It certainly makes it harder for either the foreign secretary or the prime minister to organise an early visit to Washington, as is being planned.

The questions that ensue from Mr Trump's Twitter diplomacy matter and are hard to answer.

What must the UK do to bridge the huge divide between it and the new administration?

How much further discourtesy will Theresa May tolerate?

And, perhaps most vexing of all for the government, might it just have to exploit Mr Farage's contacts, however disagreeable that might be?

But let us return to the British residence in Washington that Mr Trump wants Friend Farage to inhabit.

It was built in the 1920s at a time of poor Anglo-US relations, a building designed to show the growing economic power that the British Empire was still a force to be reckoned with.

In November 1928, the Foreign Office's most senior diplomat on America, Robert Craigie, wrote that war between the UK and the US was "not unthinkable".

For all Mr Trump's tweets, relations are not quite that bad - for now.

- Published22 November 2016

- Published22 November 2016

- Published22 November 2016

- Published13 November 2016