What is the Article 50 case all about?

- Published

The UK's biggest constitutional case in decades - on how the government can begin the process of the UK leaving the European Union - is being decided at the Supreme Court. What is it all about?

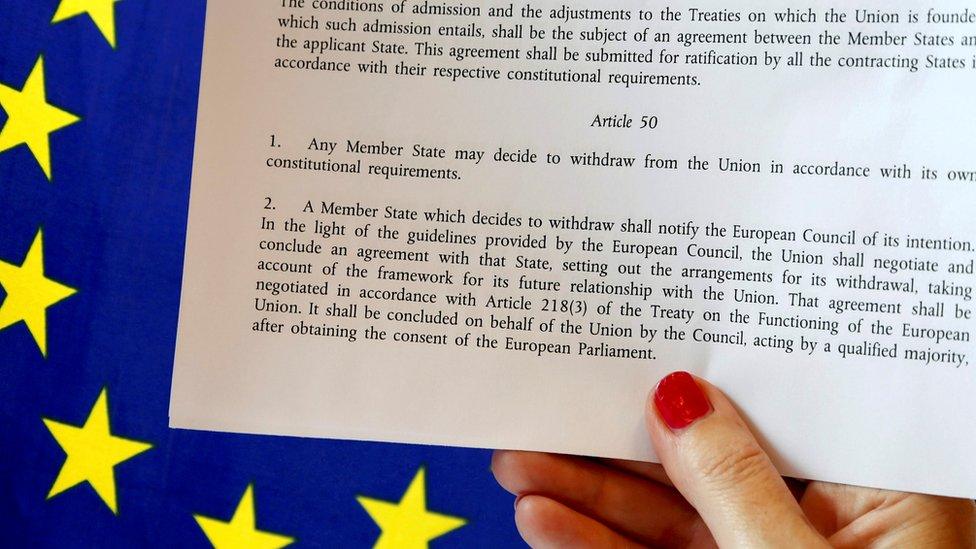

The UK's highest court is determining how the government can trigger Article 50 of the Lisbon Treaty - the document which sets out the constitutional basis of the European Union - in order to leave.

The government says it can do so without an act of Parliament, using executive powers. Its opponents in court say it cannot.

If the government loses and has to introduce a bill in Parliament, both its timetable for Brexit and its desire to keep its plans under wraps could be blown off course.

The case is not about the merits of whether the UK should leave the EU. That was decided in the referendum in June. It is about determining the lawful process under the British constitution for leaving.

Why is the case taking place?

On 3 November, three senior High Court judges, including the Lord Chief Justice Lord Thomas, head of the judiciary, ruled that the government did not have the power to trigger Article 50 using what is known as "prerogative powers".

For the first time, all 11 Supreme Court judges will hear a case together

These are a collection of executive powers - those not needing the authority of Parliament - derived from the Crown from medieval times.

Once exercised by all-powerful kings and queens, they have been dramatically reduced over centuries and the remainder are now vested in the hands of ministers.

Exercising them can be controversial because they have the effect of bypassing Parliament. But it is accepted that the government can legitimately use prerogative powers to enter into and depart from international treaties.

That is permissible because usually the exercise of these powers internationally has no effect on statutory rights in domestic law.

Thus, there is no collision with parliamentary legislation, and parliamentary sovereignty is not affected.

Who brought the case?

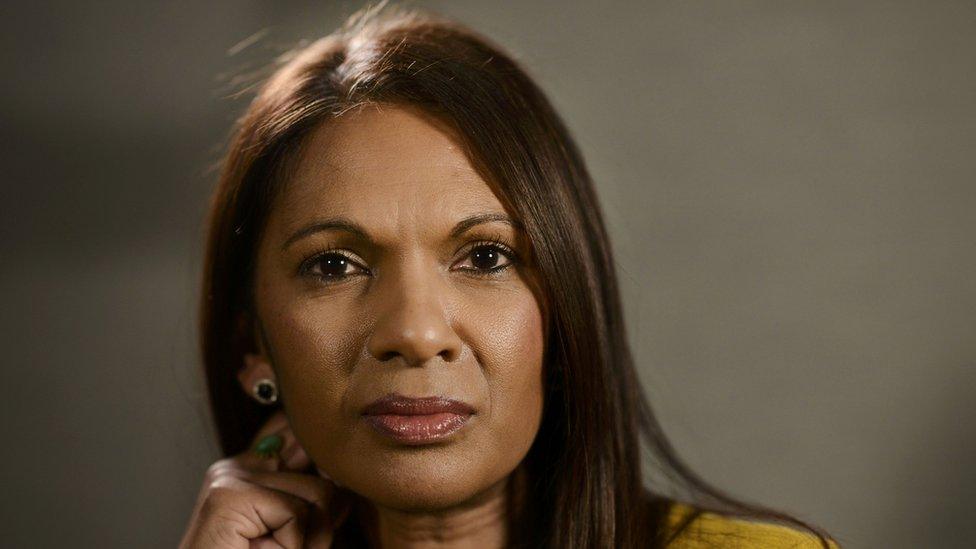

The case was brought, and won in the High Court, by two claimants. The investment manager Gina Miller and hairdresser Dier Dos Santos argued that Parliament is sovereign and the government cannot use executive powers to over-ride rights enshrined in domestic law by statute.

Gina Miller is one of two individuals who brought, and won, the initial case

They argued that such rights were brought into domestic law by the European Communities Act 1972. It is the act that took the UK into what is now the EU. In effect, they were saying that only legislation can over-ride legislation, and that therefore Article 50 can only be triggered with the authority of an act of Parliament.

The government has appealed the High Court ruling to the Supreme Court.

Who will decide the case?

It is a mark of the significance of the case that for the first time, all 11 current Supreme Court judges will sit and decide the case. This is unprecedented. It has not happened since 1876 when the court's predecessor, the Judicial Committee of the House of Lords - which sat in Parliament - was established. The case is listed to last four days with judgement expected early in the new year.

What is the government's argument and has it changed since the High Court?

The government is basically sticking with its High Court case. It argues the use of prerogative power is appropriate to give effect to the will of the British people in respect of the wholly democratic referendum result.

The government indeed says that using prerogative powers to trigger Article 50 was a "classic exercise of the royal prerogative".

If Parliament had not wanted it used, the government argued, it would have said so in the 2015 European Union Referendum Act - the law that allowed the Brexit vote.

However, there is an important change of emphasis revealed in its written case - a kind of "skeleton" argument which all sides have to provide to the court and which has been published.

The government argues that the 1972 Act is a "conduit" - simply a vehicle by which rights and obligations arrive in UK law.

Those rights and obligations are created, and changed, over time by EU treaties entered into by the UK government using the royal prerogative.

Part of the case revolves around the 1972 European Communities Act

In enacting the vehicle - the 1972 Act - Parliament was not intending to prevent the government from exercising its prerogative in the future to make or unmake treaties at the international level.

Rights and obligations having effect in domestic law through the 1972 Act could still be created, altered or removed through use of the prerogative.

And so the government concludes, contrary to the High Court ruling, it is not the case that EU rights and obligations may only be altered or removed with the prior authorisation of an act of Parliament.

How does Gina Miller's side respond to that?

Ms Miller's written case stresses the exceptional constitutional significance of the 1972 Act. It maintains that it cannot have been Parliament's intention when bringing in that act, to allow the government to use prerogative powers in international affairs to "take action to defeat or frustrate the rights Parliament had created".

It says that the principle of parliamentary sovereignty would simply not allow that. Only an act of Parliament would suffice to give the government the power to take away the rights brought into domestic law by the 1972 Act. "Clear statutory authority is needed" and "there is no such authority".

Mr Dos Santos's case supports that, stressing that what the government is proposing to do undermines parliamentary sovereignty. "Once treaty obligations are committed in domestic law. These laws cannot be removed simply by withdrawing from the treaty," it says.

What about Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland?

The Scottish and Welsh governments have been given permission to "intervene" in the case. This has been granted because they represent large constituencies of those affected by the court's decision.

The Scottish and Welsh governments have been given permission to "intervene" in the case

Scotland and Wales have devolved governments. They have responsibilities over a range of things, including health and education.

Both governments are focusing their legal arguments on something called the Sewel Convention. A convention is a generally accepted rule of behaviour. This one recognises that the UK Parliament in Westminster will not usually legislate on devolved matters without the consent of the devolved parliament. It is now part of the Scotland Act 1998, so has statutory force in Scotland.

Both the Scottish and Welsh governments argue that the UK government cannot trigger Article 50 using prerogative powers alone, and that an act of Parliament is needed. That act will affect devolved matters and so the consent of the devolved governments is required.

Consent is a particularly politically contentious issue in Scotland, where 62% voted to remain in the EU.

The Northern Ireland government has become involved as a result of a Brexit challenge by local campaigners and politicians.

They argued that Article 50 could not be lawfully triggered without a vote in Parliament. The Northern Ireland government supports the UK government's position that an act of Parliament is not required to trigger Article 50. The Supreme Court will consider both sides of the argument as it affects Northern Ireland.

Additional issues

The court will also consider issues relating to the rights of particular groups of people, including British ex-pats abroad, foreign workers in the UK and children, who face losing rights when the UK leaves the EU. These points have been raised by a variety of groups.

Will this case mark the end of the legal process?

Attorney General Jeremy Wright will lead the government's appeal

Yes, on the issue of the authority to trigger Article 50. However, there is a potentially important caveat. All sides acknowledge that once triggered, Article 50 is irrevocable.

But Article 50 itself does not specifically address this issue. Some lawyers and legal academics believe it can be revoked. If the Supreme Court feels that it needs clarification on the meaning of Article 50 and its "revocability" in order to decide the case, then it is bound to refer the matter to the European Court of Justice, in effect, the EU's Supreme Court.

That would take months and would cause political ructions. The irony of the EU's highest court having any kind of role and influence in determining how the UK exits the EU would be a very bitter one for those who voted Leave.

Which lawyers will fight the case?

The case will provide an opportunity to see and hear some of the finest lawyers in the land, some might even say "legal royalty". The government is represented by the Attorney General Jeremy Wright QC and James Eadie QC, who as First Treasury Counsel or "treasury devil", is the government's go-to independent barrister on legal issues of national importance.

Up against them for Gina Miller is Lord Pannick QC, generally acknowledged as the outstanding barrister of his generation in cases of public law. Lord Pannick and James Eadie belong to the same barristers' chambers, but there will be no quarter given in their exchanges.

A glittering array of QCs will represent Dier Dos Santos, the Welsh government and a range of others granted the status of "interested parties". Not to mention the Lord Advocate of Scotland, W James Wolffe QC and the Attorney General of Northern Ireland John F Larkin QC.

- Published3 November 2016

- Published31 October 2016

- Published25 September 2019