National Archives: Thatcher's poll tax miscalculation

- Published

It was Margaret Thatcher's biggest political misjudgement - and brought her career as prime minister to an ignominious end.

The poll tax (or community charge) was supposed to make local council finance fairer and more accountable. Instead it triggered civil disobedience and riots and a rebellion in the Conservative Party.

Cabinet papers for 1989 and 1990, released today at the National Archives in Kew, reveal the reaction to the crisis at the heart of government. They show how involved the prime minister herself was.

And they pinpoint the moment it dawned on her that her flagship policy had turned into a political disaster which was hitting, not Labour local councils, but her natural supporters.

The size of the files alone - there are nine thick manila folders compiled over 18 months - are evidence of how far the poll tax dominated government thinking. Mark Dunton, a specialist in modern records at the National Archives, calls it a "juggernaut".

Though simple in principle the tax proved to be immensely complex in practice. The files are full of highly technical papers - many of them annotated by Mrs Thatcher.

One of the National Archives' specialists says the poll tax files are a "juggernaut"

They also include a warning from April 1989 that she risked a fine if she didn't complete her own registration form on time.

But the technical challenges of introducing the tax paled beside the political problems it threw up.

The government had expected opposition to a measure specifically targeted at high-spending, mainly Labour-controlled, councils. What they hadn't expected was the reaction from their own supporters, as the April 1990 date for its introduction in England and Wales drew near.

In September the previous year her environment secretary, Chris Patten noted "a good deal of pressure developing" and Nigel Lawson, who was to resign as chancellor the following month, told Mrs Thatcher: "We are faced with a potentially difficult Parliamentary situation."

By January, Patten was telling her there could be as many as 83 rebel MPs on the Tory benches. And she got a powerful sense of the anger among formerly loyal Conservative voters in March when a constituent of the Norfolk MP Ralph Howell wrote to her.

Mr WE Jones and his wife were in their 70s, living on modest pensions, and under the poll tax would be paying more than twice what they paid under the old system of rates, while better-off people in large houses would be paying less. He accused the prime minister of being uncaring.

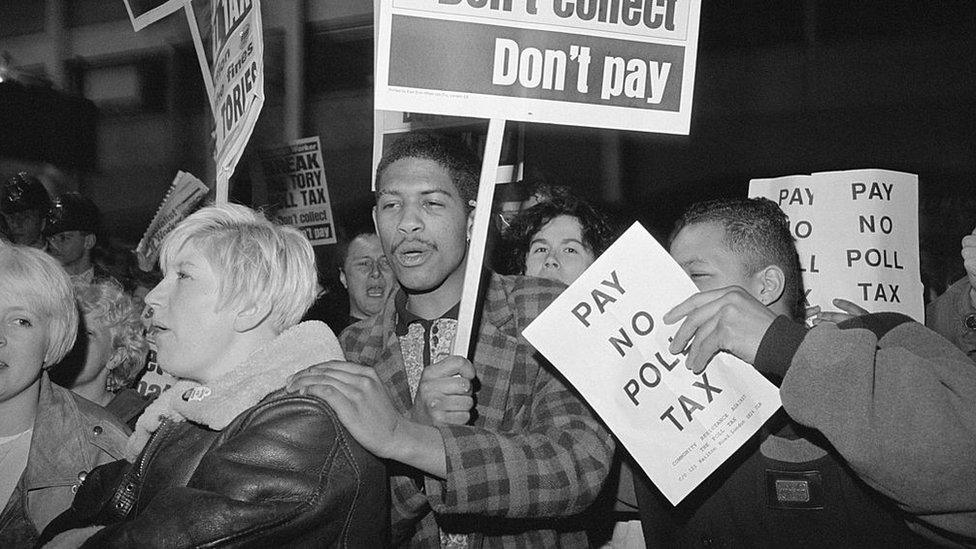

A major poll tax demonstration in London in March 1990 ended in violence

"You have taken advantage of your position to impose your will upon us to the point where you are now virtually a Dictator riding roughshod over anyone who opposes you," he wrote on 3 March.

In the files released today the couple's address has been redacted, though a later memo reveals they lived in a house called Dream of Delight in the village of Great Snoring.

Howell asked for a meeting. The prime minister's adviser Mark Lennox-Boyd suggested he should be granted an audience: "The meeting will be a waste of time, but I am afraid she will have to do it to keep his frustration at bay."

Yet the files suggest it may not have been a waste of time, for this was the point when Mrs Thatcher finally realised that something must be done.

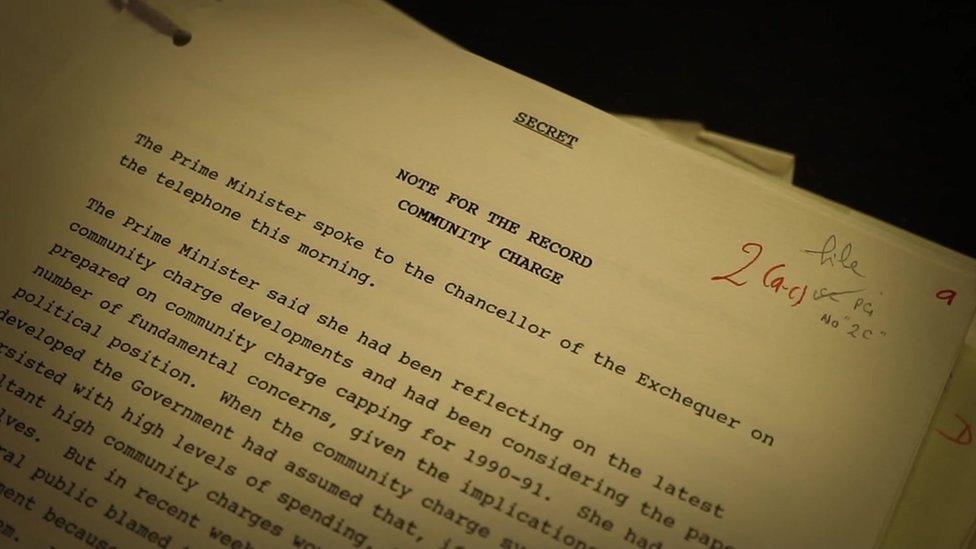

She turned not to her environment secretary Chris Patten, who had the job of bringing in the new tax, but to her recently-appointed chancellor, John Major. On 25 March (six days before an enormous demonstration against the poll tax in London which developed into serious rioting) the files contain a "note for the record" of a phone conversation between the two.

Environment secretary Chris Patten (r) was charged with introducing the poll tax

Instead of the tax shining a spotlight on spendthrift local councils, she said, the government was getting the blame for high charges, and the impact was falling on those in middle income groups, what she called the "conscientious middle".

Major agreed with the need for what he called a "radical review" to find a way to cap charges and give local authorities more money, but without increasing overall public expenditure.

Over the next two months the files reveal a succession of crisis meetings as ministers desperately tried to find a way out of their predicament, including the perceived unfairness of a system in which "Dukes and dustmen" both paid the same.

One idea was to raise more money. Should councils be allowed to use cash from the sale of council houses to subsidise the poll tax? Or should people on higher incomes pay more? That idea was floated by the prime minister herself in an unusual signed "personal minute" to Major on 9 April.

And she had another idea: putting an extra penny on a gallon of petrol and distributing the proceeds to councils. She wrote in the suggestion by hand three times on a memo of 10 April listing options. But none of her colleagues seems to have paid any attention and the idea went nowhere.

Michael Portillo says he and Chris Patten wanted to "take the guts out" of the poll tax

Meanwhile there was a growing split. Patten and the local government minister Michael Portillo wanted to increase central government grants to local authorities. Mrs Thatcher wasn't having it. "No," she wrote firmly in the margin on one occasion.

Then she and Major, without apparently consulting Patten, came up with an idea for allowing local councils to levy a higher poll tax than stipulated by central government, provided they first put it to a local referendum (a "poll tax poll").

Patten was opposed, believing the necessary legislation would be "massive in its political significance" and difficult to get through Parliament. One of Mrs Thatcher's private secretaries, Barry Potter, suggested that Patten was feeling "bruised" at being ignored.

By the end of June Potter told the prime minister that Patten and Portillo, still arguing for more government funds, were now "isolated".

Today Michael Portillo says he and Chris Patten really wanted to find a way effectively to abolish the poll tax: "We wanted to take the guts out of it, take the bits that were hurting out of it… but we recognised for her sensitivity that it would still have to be called the poll tax."

Margaret Thatcher resigned as prime minister in November 1990

They also believed the problem would take central government money to resolve. "It's worth remembering that when the poll tax was eventually replaced by the council tax, it cost about £6bn in money of the day - an enormous amount. And I'm pretty sure that Chris Patten and I were asking for only a fraction of that," says Mr Portillo.

As to the lessons to be learnt from the debacle, he draws a parallel between the decision to introduce the poll tax "without thinking it through" and David Cameron's decision to hold a referendum on Europe without thinking through the consequences.

"The lesson ought to be, think carefully before you do things. But the chances of prime ministers learning that are, I think, slim."

But nothing worked. The practical difficulties and the political pressures were too great and Mrs Thatcher's career was foundering. In November Michael Heseltine, an outspoken critic of the poll tax, triggered a leadership contest from which John Major emerged the winner.

He appointed Heseltine as environment secretary, increased VAT to generate extra cash for councils and announced the abolition of the community charge, and its replacement by council tax, in March 1991.

- Published20 July 2015