MRI pioneer and Nobel laureate Sir Peter Mansfield dies

- Published

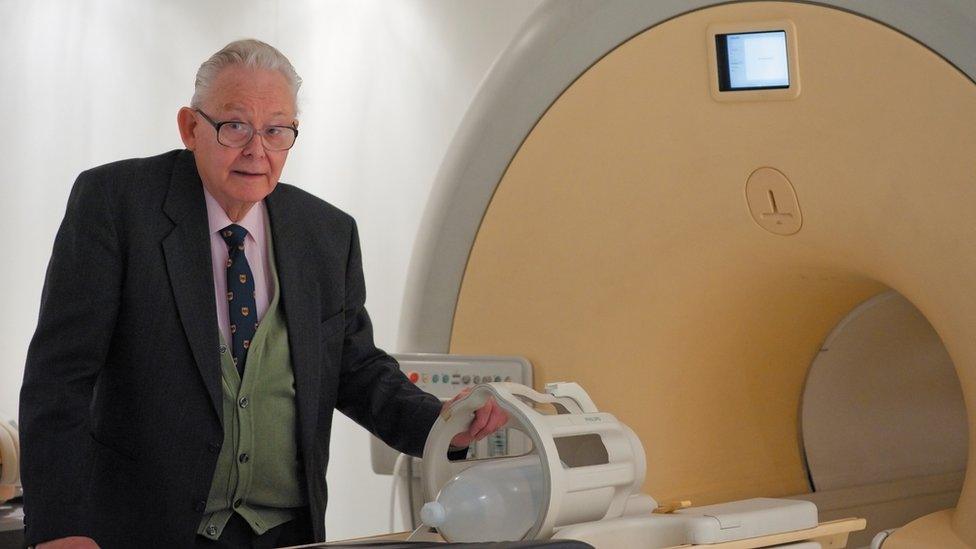

Professor Sir Peter Mansfield pioneered MRI technology

A Nobel laureate who failed his school exams before going on to pioneer body scanning technology has died aged 83.

Sir Peter Mansfield led a team in the 1970s that developed Magnetic Resonance Imaging, one of the most important breakthroughs in modern medicine.

The son of a gas fitter, he left school at the age of 15 before embarking on a career at the University of Nottingham.

Vice-chancellor Professor Sir David Greenaway said his work "changed our world for the better".

Rocketry

MRI scans generate 3D images of the body's internal organs without potentially harmful X-rays by utilising strong magnetic fields and radio waves.

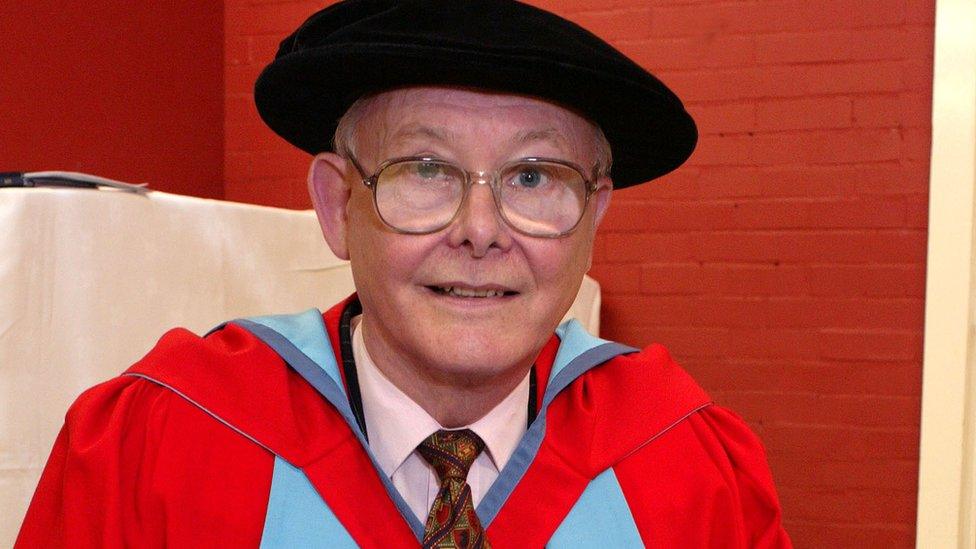

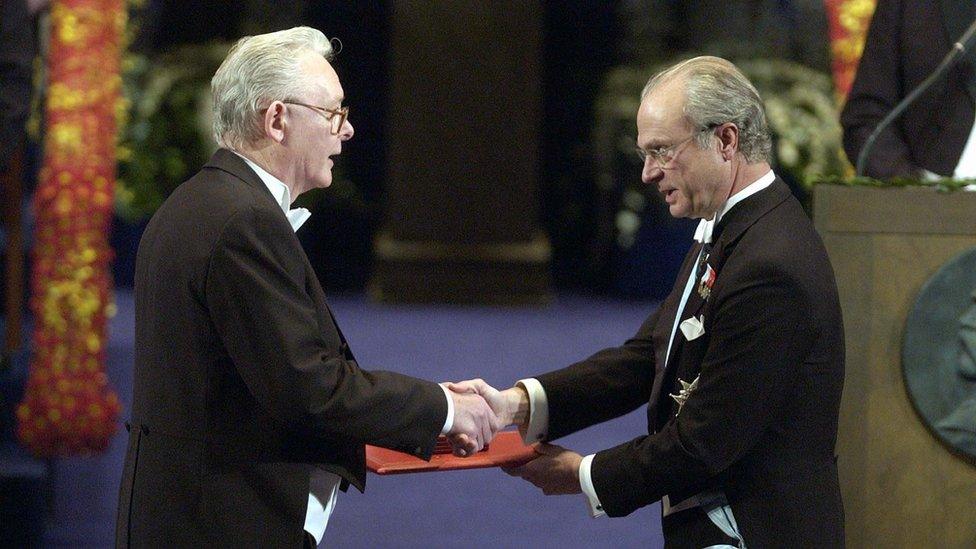

Sir Peter shared the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine in 2003 with the inventor of the technique, US chemist Professor Paul Lauterbur.

He is credited with further developing the technology, showing it can be mathematically analysed and interpreted, creating scans that take seconds rather than hours and generating much clearer images.

In his own biography on the Nobel Prize website, external, Sir Peter recalls growing up in Lambeth, south London, and being evacuated during World War Two.

He failed his 11-plus exam and attended a central school and a secondary modern school.

Sir Peter then worked as a printer's assistant until an interest in rocketry helped him secure a job at the government's rocket propulsion department in Westcott, Buckinghamshire.

He completed national service and at the age of 21, studied for A-levels part time and obtained a degree in physics at Queen Mary College, University of London.

He joined the University of Nottingham as a physics lecturer in 1964 and remained there until his retirement 30 years later.

Defining influence

In a statement issued through the university, Sir Peter's family said: "As well as being an eminent scientist and pioneer in his field, he was also a loving and devoted husband, father and grandfather who will be hugely missed."

In 1978, Sir Peter ignored warnings he could be putting himself in danger and became the first person to step inside a whole-body MRI scanner so that it could be tested on a human subject.

And only last month, he joined former colleagues to celebrate the 25th anniversary of the opening of the Sir Peter Mansfield Imaging Centre at the University of Nottingham.

Sir David said: "Few people can look back on a career and conclude that they have changed the world. In pioneering MRI, that is exactly what Sir Peter Mansfield has done."

There was also a tribute from Sir Peter's friend, Prof Peter Morris, who was a young PhD student when he first worked with Sir Peter in the 1970s.

Prof Morris, who still works at the university's school of physics and astronomy, said: "MRI has lost the rock on which it was founded.

"Sir Peter's pioneering research has revolutionised diagnostic medicine and all of us have felt its benefits.

"He has been the defining influence on my life as supervisor, colleague and friend. We will not see his like again."

The university said Sir Peter's invention of the fast scanning technique, known as echo-planar imaging, underpins the most sophisticated MRI applications in clinical use.

It said Sir Peter's work "transformed neuroscience and physiology research by opening windows on the working brain and body" - helping doctors to detect cancer and look for subtle abnormalities in brain activity in patients with attention deficit hyperactivity disorder, schizophrenia and Alzheimer's disease.

Sir Peter was joint recipient of the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine 2003

- Published26 May 2013