The child abuse scandal of the British children sent abroad

- Published

Buildings at Bindoon were constructed by migrant children

For several decades, the UK sent children across the world to new lives in institutions where many were abused and used as forced labour. It's a scandal that is still having repercussions now.

Imagine the 1950s, in the years before air travel became commonplace or the internet dominated our lives. Imagine being a child of those times, barely aware of life even in the next town. An orphan perhaps, living in a British children's home.

Now imagine being told that shortly you would board a ship for somewhere called Australia, to begin a new life in a sunlit wonderland. For good. No choice.

It happened to thousands of British children in the decades immediately following World War Two, and they had little understanding of how it would shape their lives.

The astonishing scandal of the British child migrants will be the first subject for which the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse will hold full public hearings. It's first because the migrants are now nearing the end of their lives.

Clifford Walsh stands in the port of Fremantle near Perth in Western Australia.

He is now 72. Fremantle is where, in 1954, aged nine, he stepped off the ship from London, looking for the sheep he'd been told outnumbered people in Australia 100 to one.

He ended up at a place called Bindoon.

The Catholic institution known at one point as Bindoon Boys Town is now notorious. Based around an imposing stone mansion in the Australian countryside, 49 miles north of Perth, are buildings Walsh and his fellow child migrants were forced to build, barefoot, starting work the day after they arrived.

The Christian Brothers ruled the place with the aim of upholding order and a moral code. Within two days of arriving he says he received his first punishment at the hands of one of the brothers.

"He punched us, he kicked us, smashed us in the face, back-handed us and everything, and he then sat us on his knee to tell us that he doesn't like to hurt children, but we had been bad boys.

"I was sobbing uncontrollably for hours."

His story is deeply distressing. He tells it with a particularly Australian directness. He is furious.

A teacher reads to a group of children in Stevenage who are about to be sent to the Fairbridge school in Molong

He describes one brother luring him into his room with the promise he could have some sweet molasses - normally fed, not to the boys, but the cows. The man sexually abused him.

He claims another brother raped him, and a third beat him mercilessly after falsely accusing him of having sex with another boy.

"We had no parents, we had no relatives, there was nowhere we could go, these brothers - these paedophiles - must have thought they were in hog heaven."

He has accused the brothers at the Australian Royal Commission into Institutional Responses to Child Sexual Abuse, the first time he has fully disclosed his experiences.

At the time he says: "I was too terrified to report the abuse. I knew no other life.

"I've lived 60 odd years with this hate, I can't have a normal sexual relationship because I don't like to hold people," says Walsh. "My own wife, I couldn't hug."

He was troubled by all the memories.

"I couldn't show any affection. Stuff like that only reminded me of what the brothers would do all the time."

Britain is perhaps the only country in the world to have exported vast numbers of its children. An estimated 150,000 children were sent over a 350-year period to Virginia, Australia, New Zealand, Canada, and what was then Southern Rhodesia, now Zimbabwe.

Australia was the main destination in the final wave between 1945 and 1974.

There were twin purposes - to ease the population of orphanages in the UK and to boost the population of the colonies.

The children were recruited by religious institutions from both the Anglican and Catholic churches, or well-meaning charities including Barnardo's and the Fairbridge Society. Their motivation was to give "lost" children a new life, and it would be wrong to say that every one of Britain's exported children suffered.

But for too many, the dream became a nightmare. Hundreds of migrant children have given accounts of poor education, hard labour, physical beatings and sexual abuse.

A demonstration of boxing at the Fairbridge school in Pinjarra, Western Australia

Attempts were made to recreate a happy home life. At the Fairbridge Farm School in Molong, four hours outside Sydney, children lived in cottages, each with a "house mother".

Fairbridge was not a religious order, like the Christian Brothers, and some of its former children have praised the start it gave them.

But not Derek Moriarty. He was at Molong for eight years, one of hundreds of children to have endured poor food, inadequate education and physical labour. His life has been deeply affected by his Fairbridge upbringing.

He suffered at the hands of the then-principal of the school, Frederick Woods, a man he says kept 10 canes, and to the horror of the children, a hockey stick - which he used to beat the boys.

Boys play football at the Fairbridge school at Pinjarra

Perhaps inevitably, Moriarty alleges sexual abuse - by a member of staff who took his clothes off and touched him.

"I was nine or 10," he says, "and I didn't understand it." He eventually ran away from Molong, attempted suicide at the age of 18 and has always suffered from depression, not helped by the years it took to discover the details of his family back in the UK.

In 2009 the Australian government apologised for the cruelty shown to the child migrants. Britain also made an apology in 2010.

The pressure for answers and reparations had been growing. Questions might never have been asked, had it not been for two seekers of the truth.

In the early 1980s a Nottingham social worker, Margaret Humphreys, came across Australian former migrants who had suddenly started to realise they might have living relatives in the UK.

Many had been told, as children, their parents were dead. It wasn't true. "It was about identity," she says, "being stripped of it and being robbed of it."

Her life's work has been about reuniting "lost children" with their lost relatives. Having reinstated their sense of identity, she went on to build a lifelong bond with many former migrants, and they began to disclose the physical and sexual abuse they had suffered.

"As you go along, you're learning more and more about the degrees and the awfulness of the abuse. That's been incremental because people can really only talk about it over a longer period of time when there is trust. There's a lot of trauma involved here."

David Hill sailed out of Tilbury bound for a Fairbridge farm school

Further revelations about the Fairbridge homes were uncovered by one of their own.

David Hill was shipped out from Britain with his brothers to the Fairbridge farm at Molong in 1959. He was one of the lucky ones. His mother followed him later, providing him with a stable future.

He became a highly successful public figure in Australia. He was chairman and managing director of the Australian Broadcasting Corporation, and is a keen historian. Hill brought together the Fairbridge boys and girls to tell him their stories. Like those from the west of Australia - they were dominated by beatings and abuse.

Derek Moriarty was among those who unburdened themselves for the first time to Hill, as part of the research for his 2007 book The Forgotten Children and a 2009 ABC television documentary.

"I felt a weight lifted off my shoulders when I told him," Moriarty says. "But my abuse paled into insignificance compared to some others."

David Hill's work triggered claim after claim from men and women about their experiences as children.

Children gather at the Fairbridge school at Molong

They wrote and told him of a litany of sexual abuse. There was no sexual education at the school and, failing to understand what was happening, they were left traumatised.

Hill makes the astonishing claim that 60% of the children at Fairbridge Molong allege they were sexually abused, based on more than 100 interviews.

The Australian law firm Slater and Gordon successfully claimed compensation on behalf of 215 former Fairbridge children, of whom 129 said they had been sexually abused.

For the Christian Brothers the figures are even higher. The Australian Royal Commission on child abuse recently revealed 853 people had accused members of the order.

Hill is one of the expert witnesses who will give evidence to the UK Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse (IICSA). The inquiry has been bitterly criticised since its creation - and some have questioned its huge scope.

Is there any point in it considering the history of child migration, dating back so far?

Children at Pinjarra hear a speech by the Duke of Gloucester

The Australian Royal commission is examining child migration closely. In 1998 the UK's Health Select Committee also held hearings, in which the Child Migrants Trust described the Christian Brothers institutions as "almost the full realisation of a paedophile's dream".

But the committee did not get to the bottom of it, concluding: "The Christian Brothers were very insistent that the abuses were not known to those who controlled these institutions. We cannot accept this."

Sources close to the current public inquiry have told the BBC it will produce new and startling revelations about the scale of sexual abuse abroad, and attempts by British and Australian institutions to cover it up.

This will include an examination of the claims of some child migrants that they were sent abroad weeks after reporting sexual abuse at their children's home in the UK. The allegation is that they were hand-picked. Either to get them out of the way, or because they were of interest to paedophiles.

Three former Fairbridge boys have claimed that the then-Australian Governor General, Lord Slim, sexually molested them during rides in his chauffeur-driven Rolls Royce while visiting the home. It is understood these allegations could be considered by the inquiry.

The inquiry could also definitively answer a crucial historical question. Did the British government know it was sending children to be mistreated in a foreign country?

Margaret Humphreys is adamant: "We want to know what happened, we want to know who did it, and we want to know who covered it up for so long."

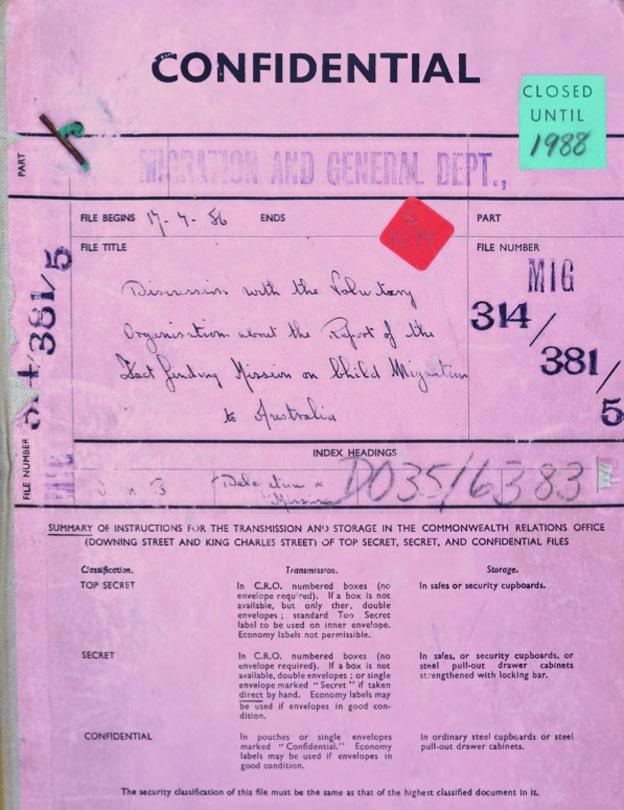

In fact, government files reveal that there was a time when the migration programme could have been stopped. It came in 1956 when three officials went to Australia to inspect 26 institutions which took child migrants.

There was enough warning of this "fact-finding mission" to allow a Fairbridge official to warn the manager of the Molong farm: "It would be advisable to see (the children) wore their socks and shoes." Even in a land where it was easy to encounter poisonous wildlife, that wasn't standard practice at many of the institutions.

The resulting report, delivered back to the British government, was fairly critical. It identified a general lack of expertise in child care and worried that children were living in institutions in remote rural areas, whereas the trend in Britain was towards fostering them into urban families.

However the report had a second "secret" section, never published, which went a little further.

This named names - including those of five institutions which were not up to standard. When the UK's Home Office saw the report, it wanted five more added to create what became an infamous blacklist - places which should not receive more children because of poor standards of care. Fairbridge Molong and Bindoon were both on the list.

St Joseph's orphanage, Sydney

Dhurringile Rural Training Farm, Victoria

St Joseph's, Neerkol, nr Rockhampton, Queensland

Salvation Army Training Farm, Riverview, Queensland

Methodist Home, Magill, Adelaide

St Vincent's Orphanage, Castledare

St Joseph's Farm School, Bindoon, Western Australia

St John Bosco Boys' Town, Glenorchy, Hobart

Fairbridge Farm School, Pinjarra, Western Australia

Fairbridge Farm School, Molong, New South Wales

But the report had barely scratched the surface. It made no mention of sexual or physical abuse.

Given the length of time it took for the child migrants to tell their stories, this is perhaps unsurprising.

But during the post-war years, sexual accusations were made against three principals of the Fairbridge Farm School at Molong.

David Hill has revealed they included a claim that Frederick Woods - the man who beat boys with a hockey stick - was "sexually perverted" and had abused a girl resident. An internal investigation exonerated him.

This does not appear to have been disclosed by the Fairbridge Society either to the public or the 1956 inspectors. They had a schedule to keep to, and their visits to institutions spread across a vast country were fleeting.

Like the UK, there has been outrage in Australia over historical child abuse

Similarly, at the Christian Brothers' homes in Western Australia, children were terrified of criticising the brothers.

Former Bindoon resident Clifford Walsh was there during the fact-finding mission. He doesn't remember it, but says speaking out would have resulted in an extremely severe, possibly even life-threatening, beating.

The truth is that neither the institutions, nor the inspectors, came close to creating the sort of atmosphere where children could tell them their darkest secrets and be taken seriously. If that had happened, not just in Australia, but throughout modern British history, we might not have needed the current public inquiry.

It might have missed the crimes being committed in the institutions, but when the 1956 report hit the desks of Britain's bureaucrats it created quite a stir.

Something strongly resembling a cover-up began. Files held at the National Archive set out the response of government officials. One wrote in 1957 that the Overseas Migration Board, which advised the government, was "sorry the mission was sent at all".

After a series of changes at the top, Alexis Jay is now the head of the British inquiry

Some on the board "urged very strongly that the report should not be published."

The government archives record that at a meeting with the organisations running the migrant programmes, Lord John Hope, under-secretary of state for Commonwealth relations, discussed what would be disclosed to parliament from the report.

"I think you can rely upon us to do what we can in as much as we shall pick out all the good bits," he said. "I shall not be in the least critical in Parliament."

The UK Fairbridge Society piled on its own pressure - its president was the Duke of Gloucester, uncle to the Queen. Officials discussed the "immediate parliamentary repercussions" which could result from holding up the migrant programme.

Sir Colin Anderson, the director of the Orient Line, which benefited from the business of shipping the children, appealed for the report not to be made public because of the controversy it might cause.

The Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse

The inquiry into historical child sex abuse in England and Wales is to examine claims made against local authorities, religious organisations, the armed forces and public and private institutions

Momentum for the inquiry started with the Jimmy Savile scandal

The inquiry is expected to take about five years to complete

The first phase of the inquiry will consist of 13 separate investigations

In a sympathetic phone call, a senior official from the Overseas Migration Board responded that the Fairbridge Society was an "extremely fine endeavour for which everyone felt the highest praise".

And what did the government do? Files at the National Archive show officials squirmed in institutional discomfort at the idea of taking any meaningful action.

In June 1957 the Commonwealth Relations Office sent a secret telegram to the UK High Commission in Australia - "we do not want to withhold approval", it said, for more children to to be sent from the UK.

After more pressure from the Fairbridge Society, 16 children waiting to travel were sent on their way.

The key recommendation of the inspectors, that the British home secretary agree each and every decision to send a child, was quietly shelved.

The Fairbridge Society continued to ship out children, though concentrated on those whose mothers intended to join them later.

David Hill's response is anger, even today. With tears in his eyes he says: "I'm surprised how vulnerable it has made me feel - that it could happen and happen to the extent that it did.

"The British government not only continued to approve children to be sent, but they financially subsidised for them to go. To institutions they had put on a blacklist unfit for children, condemned."

Molong Farm School finally closed in 1973. The Fairbridge Society is now part of the Prince's Trust and still runs activity holidays for children.

The Prince's Trust said it had never been involved in child migration, "but we do hold the archive of the former Fairbridge Society. We are cooperating fully with this important inquiry."

Bindoon remained open until 1966. It is now used as a Catholic college.

The Australian Royal Commission recently estimated that 7% of the country's Catholic priests were involved in child abuse.

And such is the scope of sexual abuse allegations in the Catholic and Anglican churches in the UK that entire strands of the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse are dedicated to them.

The IICSA investigation will be able to seize the records, not just of the British government but also the migration institutions themselves - including the archives of the Fairbridge society.

Sixty years later, former Bindoon boy Clifford Walsh strongly believes this inquiry can help answer some of his questions about the culpability of the government and British institutions.

"They sent us to a place that was a living hell. How come they didn't know that? Why didn't they investigate? And if they investigated, then they were incompetent or there was a cover-up."

The child migration programme will also provide ample evidence for the UK's effort to consider the long-term effect of child sexual abuse. Something which may turn out to be a central theme of the inquiry.

Historian and Fairbridge boy David Hill estimates it took victims he interviewed 22 years on average before they felt able to disclose what happened.

But it will also provide a final chance for Britain's lost children to return to the land of their birth and tell their stories. The anger has not gone away, and their childhoods have left invisible scars which have lasted a lifetime.

One of the child migrants we spoke to asked us not to name him, after he returned to Bindoon armed with a sledgehammer.

His target? The ostentatious burial place of Brother Paul Keaney the institution's founder. By the time he'd finished, enough damage had been done to the marble grave slab that Bindoon's current owners, a Catholic college, were forced to remove what remained.

It was one man's small blow against a history of child cruelty.

Have you been affected by abuse?

The Child Migrants Trust, external attempts to reunite children sent abroad with their families

NSPCC, external specialises in child protection

National Association for People Abused in Childhood, external offers support, advice and guidance to adult survivors of any form of childhood abuse

Survivor Scotland, external offers help to improve the lives of survivors of childhood abuse in Scotland

Childline, external is a private and confidential service for children and young people up to the age of 19

The Children's Society, external works to support vulnerable children in England and Wales

Stop It Now!, external supports adults worried about child abuse, including survivors, professionals, those with a concern about their own thoughts or behaviour towards children and friends and relatives of people arrested for sexual offending