London attack: What security chiefs have long been preparing for

- Published

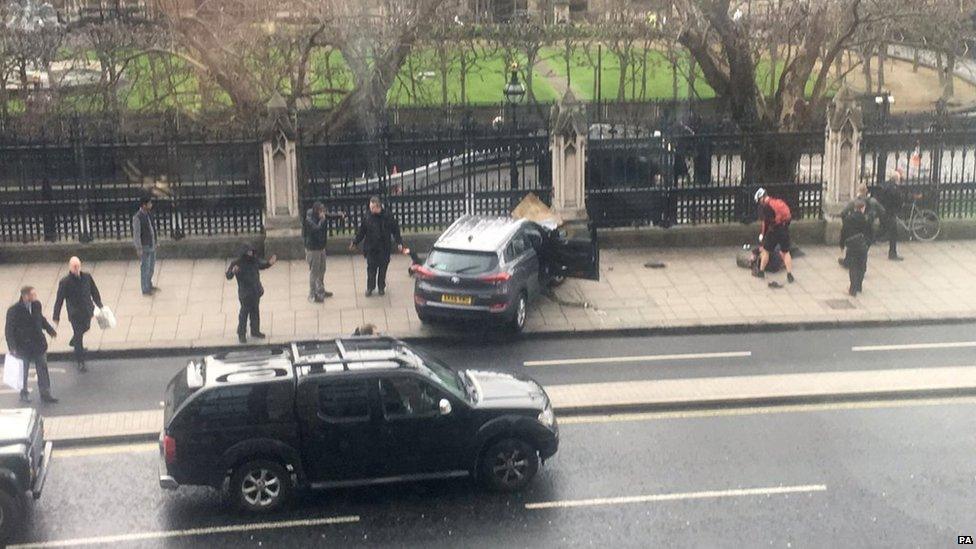

The carnage on Westminster Bridge and inside the grounds of Parliament is the attack that security chiefs here in the UK have long been preparing for.

Terrorism looks not just to kill and maim - but to create panic and such a sense of disorder that it rocks a city or nation to its foundations.

The days when terrorism meant large, complex bombs and months of planning are gone

And this attacker sought to do so in as low-tech way as is possible.

The days when terrorism exclusively meant large, complex bombs and months of planning are largely gone: western security agencies - particularly MI5 and its partner agencies - are very, very good at identifying those plots and disrupting them.

The longer it takes to plan such an attack, the more people who are involved, the more chances there will be for security services to learn what is going on.

Since the 2005 suicide attacks, the police have trained and trained and trained for how they would manage a repeat of that atrocity.

Those plans have been repeatedly refined - most particularly in the wake of the marauding attacks on Mumbai in 2008 and the horrifying scenes in Paris, Nice and elsewhere.

Part of that training has been how to deal with the attacker himself - and some of it has been about how to manage a city; to keep it moving, living and breathing.

And that's why the prime minister was able to say Londoners will carry on as normal.

Electronic trail

The attack began with the assailant driving into people on Westminster Bridge.

It's a method of attack that has been repeatedly encouraged by groups including al-Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP) and the self-styled Islamic State group.

It's been promoted online in both organisations' English language magazines.

A man believed to be the suspect received medical treatment, while two knives lie on the ground

And over countless counter-terrorism trials at the Old Bailey, I have heard evidence of British suspects having this information in their possession.

Why choose this method?

Because it's simple and, potentially, undetectable until it happens.

Of the 13 foiled plots since 2013, by my reckoning around half of them contained one element or other of this attacker's methodology - either an attack involving a vehicle, or a bladed weapon and a determination to act on foot.

The two men who murdered Fusilier Lee Rigby in 2013 drove right at the soldier and then got out to hack him to death. Others with similar ideas have been stopped before they could put their plans into action.

So why did this one get through?

We now know that he was British. Prime Minister Theresa May said that "some years ago" he was once investigated in relation to concerns about violent extremism. "He was a peripheral figure," she said.

Critically, even if he had been on their radar, we don't know if he had said or done anything that merited him being prioritised over other severe threats.

The prime minister told the Commons that the case he was involved in was "historic" and he was "not part of the current intelligence picture".

Since the attack, the police have been trying to work out whether this attacker worked alone or was part of a broader network.

The likelihood is that he knows other people with the same mindset - but that doesn't mean they were part of the plan.

They will not discount the possibility that there are others out there until they have run all those investigative lines into the ground.

There have been arrests - and officers will have been analysing the electronic trail left by the attacker's car as it passed through the city's automatic number plate recognition cameras.

They will be pulling every available piece of CCTV to look for further clues - particularly the individual's starting point and last physical meetings with others.

Experts will triangulate his mobile phone's movements and look at who he was speaking to and when.

They may get a ping that puts him in the same location as a known suspect - it's happened before.

We'll never hear about it, but analysts inside MI5 and GCHQ may turn to far more intrusive techniques to hack into his online accounts to see what that will yield.

The police have trained and trained for how they would manage a repeat of the 2005 London bombings

And finally, detectives will hope that some good, old-fashioned policing will turn up a vital clue - perhaps an anonymous call to the anti-terrorist hotline or a quiet word from a neighbour to a local officer.

There are some very long hours and days ahead for investigators.

Out across the capital, the Metropolitan Police will step up its presence.

There will be more armed officers on the streets - but also more beat patrols to reassure communities.

Crucially, there will be increased monitoring for community tensions and a hate crime backlash.

There is one final question. There is a ring of steel around the Palace of Westminster - but the attacker was able to enter Parliament's grounds through the gates to New Palace Yard, which is below Big Ben.

The entrance is guarded by armed officers but, unlike other parts of Parliament, there is no elaborate chicane.

There will be inevitable questions about whether this entrance was appropriately protected - but given the rudimentary nature of this man's murderous plan, it would not have stopped him trying.