Ian Brady letters: Inside the mind of the Moors Murderer

- Published

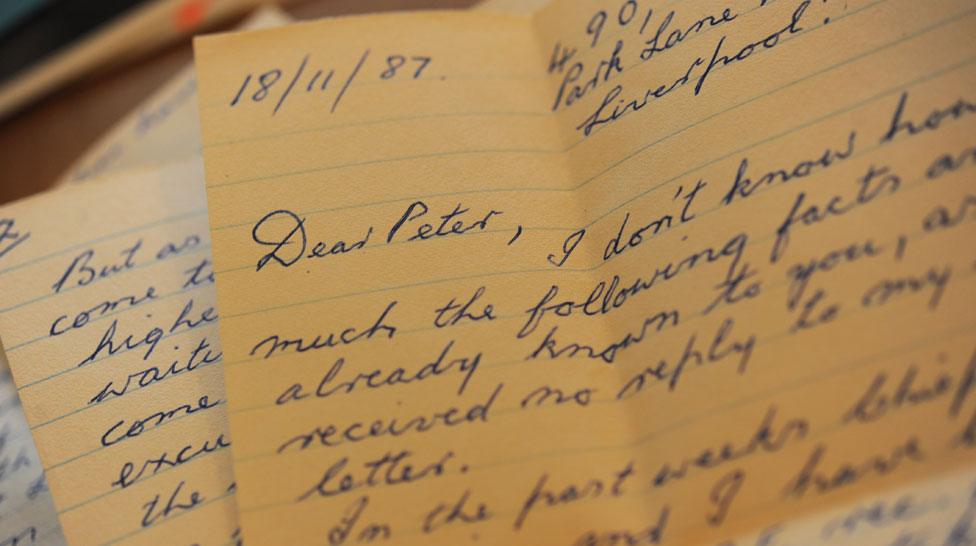

My correspondence with Ian Brady began with a simple question: are you going to apply for parole?

Given that he and Myra Hindley had committed the most shocking crimes of modern times, it was hard to imagine either of them would ever be released.

The public would surely never accept that they were reformed characters who had paid their debt to society.

Yet by 1985, the Moors Murderers had been behind bars for almost 20 years. Time was passing, and perhaps memories would start to fade.

So the question of parole was not an idle enquiry. The families of the children they killed were becoming anxious about the possibility that one day they might be free to walk the streets again.

Myra Hindley had already begun a long and ultimately futile attempt to win her freedom. She tried in vain to persuade a disbelieving world that she had been coerced into the crimes by Brady.

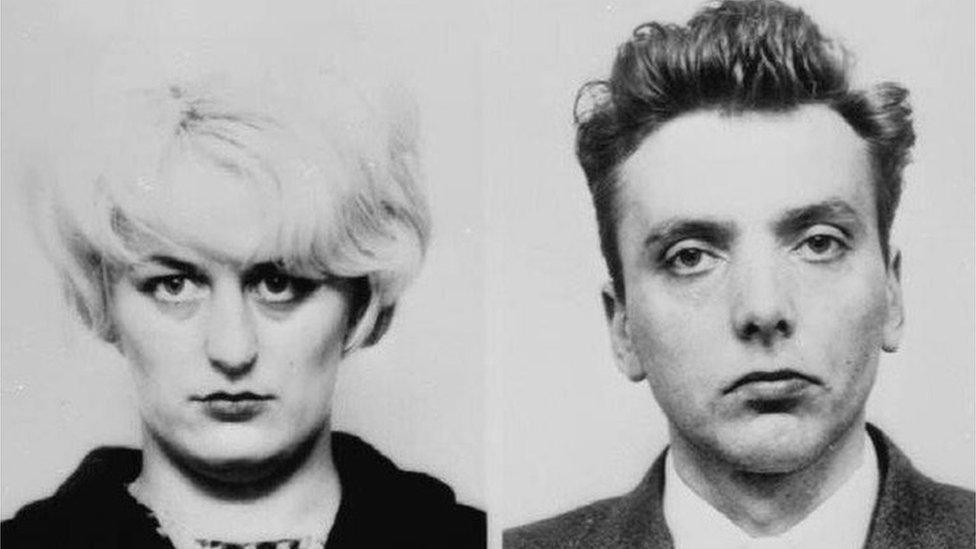

The sullen face of the peroxide blonde, captured in the famous police photograph, continued to stare out from the pages of the tabloid newspapers as each twist of the story was reported.

Brady's accomplice Myra Hindley died in 2002

"She is a good woman," Lord Longford told me more than once, as he tried to advance her case for release. A more unpopular cause to champion, it would be hard to imagine.

She was without doubt the most hated woman in Britain. Hindley died in prison in 2002, still dreaming of freedom. But back in 1985, little had been heard from Brady, and we could only guess at his intentions. Intrigued, I wrote to him and asked him if he was planning to apply for parole.

I did not expect a reply, so the arrival of a letter from Gartree Prison, from prisoner number 605217, came as a shock. As I held it in my hands, unopened, all my memories of the Moors Murders came flooding back.

Police searching on Saddleworth Moor in 1965

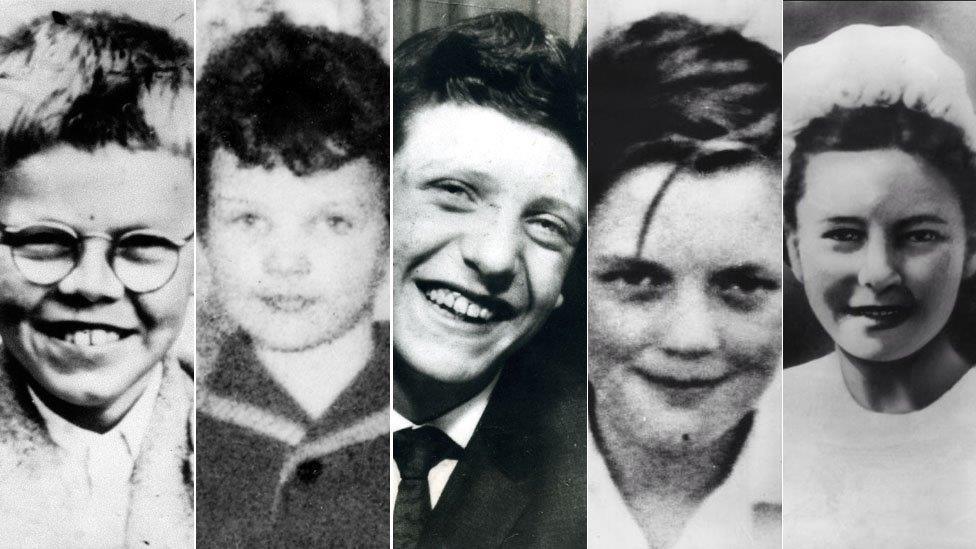

Merely to mention Brady's name was enough to make anyone alive in the 1960s shudder with horror. He and Hindley abducted and killed their young victims and buried four of them on the bleak moors, high above Manchester.

I began my career as a journalist in the North West around that time, and needed no reminding of the story.

The sight of police officers digging, searching for bodies, became an indelible memory for my generation. Along with the smiling faces of the children, captured in family snapshots, and the black and white police photographs of their killers - these images were burned into our minds.

Few crimes have caused such revulsion, or cast such a long shadow. To many people, Ian Brady was the epitome of evil, a sadist who killed without conscience. If anything, his accomplice Myra Hindley was judged even more harshly, simply because she was a woman.

So with all this in my mind, I felt uneasy as I opened the letter. It was short and came straight to the point:

"My position on parole has not altered. I take no part in the annual circus and never shall. It has always been my intention to choose the time and manner of my own death in prison. All I have sought in my twenty years in prison is an active, positive life - unsuccessfully."

Brady later told me he had been given a form to apply for parole, but had refused to sign it. When members of the parole review committee asked to see him, he said he would not talk to them. Brady thought the process was "a political farce", but it showed that parole was indeed a possibility.

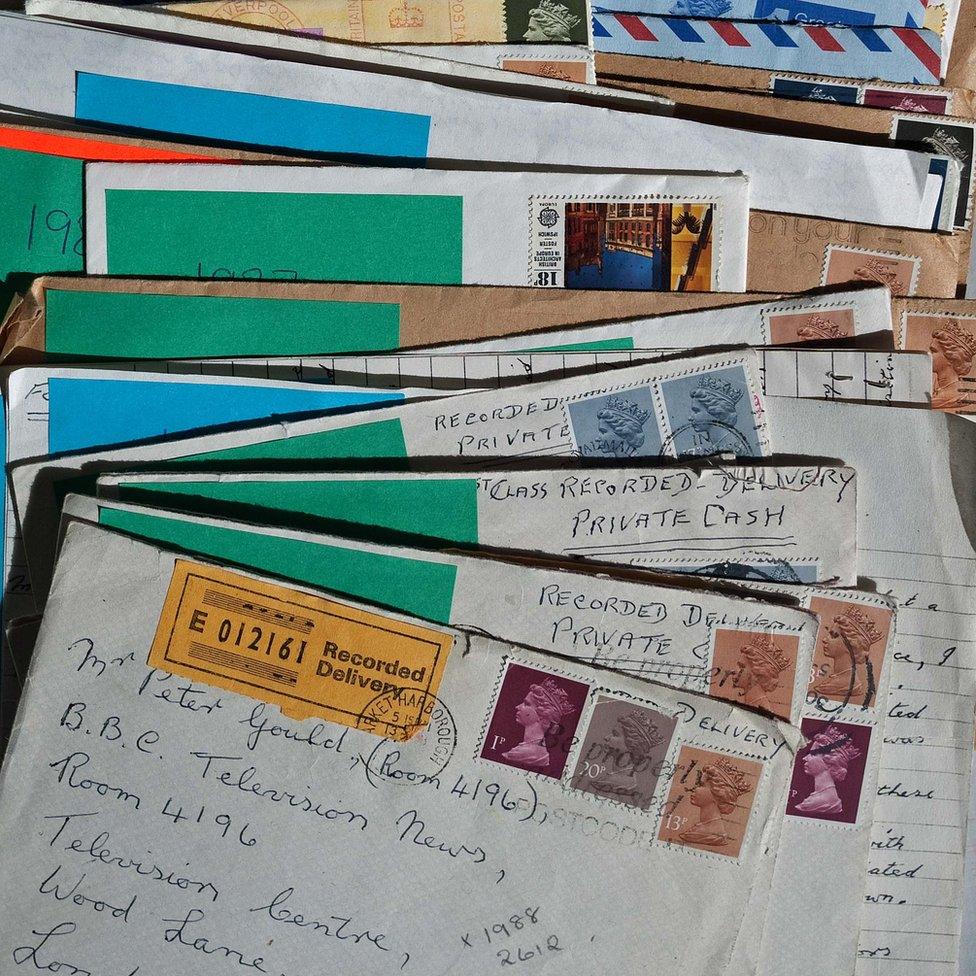

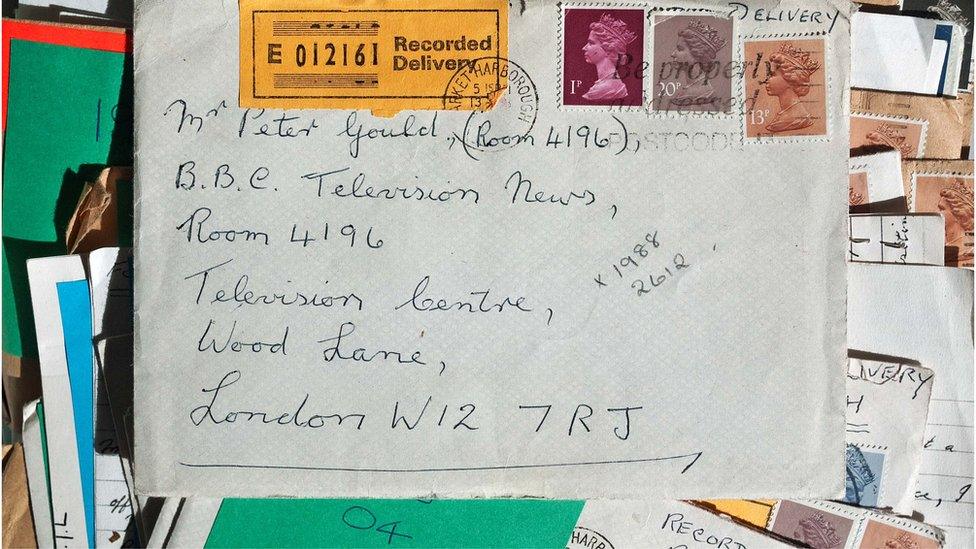

My story appeared on the BBC, and was followed up by the newspapers. And that was the end of it... or so I thought. Little did I know that Brady's brief note was to be the start of a correspondence that was to last more than 30 years.

Every few weeks, a new letter would arrive. As the pile grew, they started to give me an insight into the mind of the writer. But ultimately they prompted more questions than answers. From beginning to end, Ian Brady told me only what he wanted me to know.

I have often been asked how I could write to such a man. I had vivid memories of the crimes and I suppose I was curious to know more about Brady and what had driven him to kill.

As a journalist, I was able to approach the correspondence with a degree of detachment, but at the same time, I could not forget who he was, or what he had done.

I was clear in my own mind that he and Hindley should never be released. After Brady's initial letter, I assumed the correspondence would quickly come to an end.

But he continued to write to me from his prison cell, letters that were sometimes written in a shaky hand. He seemed under stress, mentally and physically. Despite being a man who was 6ft (1.83m) tall, his weight had fallen to around 8st (50kg).

That year, doctors concluded Brady was mentally ill and he was transferred from Gartree Prison - "the garbage can" as he described it - to Ashworth high security hospital on Merseyside, where he remained until his death.

He was soon receiving drugs as part of his treatment, and his letters became more lucid and more legible.

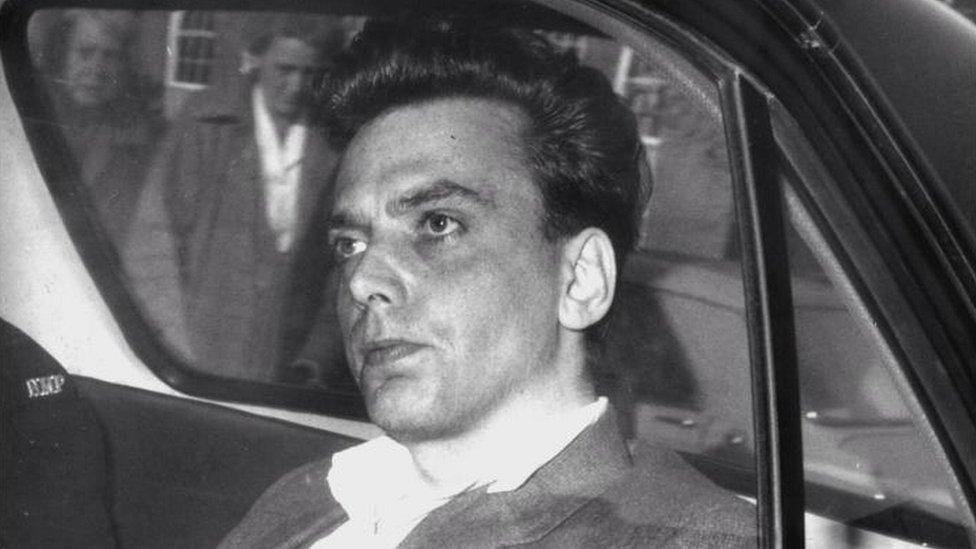

Ian Brady was jailed for three murders in 1966

They ran to many pages, initially on prison notepaper, then sheets of lined A4, the kind with very narrow spacing. They were always written with a ballpoint pen in a very neat hand, words precisely on the lines, with good grammar and correct spelling.

He did at least have the benefit of going through the Scottish education system at a time when mastering the three Rs mattered.

As I discovered, he was an avid letter-writer, with a wide circle of correspondents, although he wrote to few journalists on a regular basis.

I think it helped that I worked for the BBC, rather than one of the tabloid newspapers that wrote endless accounts of his life behind bars. Brady catalogued their inventive efforts:

"The national media allege I organised a Christmas party for the ward. I organised no such party. I ate nothing whatsoever on Christmas Day. There was a ward barbecue this afternoon, hordes of strangers waiting to gawp at the performing monkey, but I didn't take the stage. Several national newspapers allege I invited the Yorkshire Ripper, who is even not in this hospital but Broadmoor. A newspaper falsely states that I go on trips outside. I am in my cell night and day and go nowhere at all."

Yet for all his hatred of the media, it was clear that he was very aware of his status as a high-profile prisoner, and I think he enjoyed the notoriety, and being the centre of attention.

So while he railed against the stories about him that appeared on a regular basis in the tabloids, it became part of his wider battle against all those with power over his life.

In writing his letters, he certainly knew that what he said was liable to be reported, and he chose his words carefully, with an eye to publication. His relentless character assassination of Myra Hindley undoubtedly caused her great damage as she campaigned for parole.

What else did he write about? In large part his letters were a litany of complaints about his treatment at Ashworth - Trashworth in Brady's lexicon. It would not be fair on the staff to repeat his splenetic observations and unsubstantiated allegations, which covered page after page of A4.

Writing about life behind bars, he displayed a deep anger, but also an acerbic humour. It was as if he had a special dictionary in his head, reserved for pouring scorn on all those in authority whom he hated.

Peter Gould with some of Brady's letters

I soon got the impression that battling against the authorities - whoever they happened to be - was an important part of his mechanism for coping with his loss of freedom and life within a highly-regulated institution.

But the letters were more than just the paranoid rantings of a madman. I quickly discovered that he did not fit the popular stereotype of the sub-human monster, an image that most of us recognise instantly from crime thrillers on TV, and find strangely reassuring.

We do not expect serial killers to live anything approaching normal lives when they are not committing their crimes. They are certainly not supposed to display intelligence or humour.

So it was more than a little unsettling to discover that Brady was articulate and surprisingly well read, with a preference for classic literature rather than popular fiction.

The Russian writer Dostoevsky, with his explorations of human psychology, was a particular favourite.

Brady's letters were sprinkled with literary references that would send me searching through my bookshelves. His knowledge was nothing if not a testament to the education provided by prison libraries.

He made sharp observations about politics and current affairs, revealing a close interest in the world outside, a world he knew he would never see again.

He had nothing but contempt for the establishment in general, and politicians in particular:

"The Gulf - the Bore War. Thirty countries, including the most powerful in the world, against a third world Arab state, and they call it a victory. Politically, the UK is now to America what Italy was to the Germans; a servile lackey willing to bomb any country the Americans choose. The election... a non-event only of synthetic interest to the media in generating an appearance of democracy and choice, between two Tory parties."

He claimed not to be interested in reading newspapers, but little that was written about him escaped his notice. He also listened to radio news bulletins, and watched television. Several times he told me he had seen me reporting for TV news. Once, I was even talking about him.

Fortunately, perhaps, he did not have access to the internet, as he would undoubtedly have seen it as a platform. A lot of the time, he just stayed in his room, read books, and continued his writing. Somewhere, waiting to surface, there is a memoir of his life.

He once wrote a book, published in the US, intended to take the reader inside the mind of a serial killer. But significantly, it did not include any discussion of his own crimes. And in his letters to me, he was always reluctant to delve too deeply into the past, unless it was to confirm Hindley's active involvement in the murders.

It was as if he was hiding behind a mask that prevented you getting into his head. But there were times when the mask slipped, and you saw hints of an inner turmoil.

The Moors Murders victims were left to right, Keith Bennett, Lesley Ann Downey, Edward Evans, John Kilbride and Pauline Reade

In 1986, following my correspondence with Brady, the mothers of two of his victims wrote to him. His reaction on receiving their letters was revealing:

"Although I've been given them, I've not been able to bring myself to read them yet. I'm afraid to read them, understand? I have to keep the mental blocks tightly shut and keep control."

The mother of Lesley Ann Downey wanted to visit him in prison. Her request was refused by the authorities, so Brady suggested I pass on a personal message.

I was uncomfortably aware that I was becoming a go-between, a part of the story I was reporting:

"You can inform her of what I've told you. Remorse in this and other matters is axiomatic and painfully deep but I despise useless empty words and prefer positive action to balance part of the past."

To my knowledge, it was the only time he ever publicly expressed any regret for what he had done.

Perhaps, as he suggests, it was just too difficult for him to confront the reality of his crimes. But he seemed to resent being put in a position where he was expected to express remorse. He was not going to jump through any hoops for the press.

The "positive action" he refers to was his work in transcribing books into Braille for a school for the blind, something he did for many years.

A small act of contrition, perhaps, but one you may not have read about in the papers.

Brady and Hindley belatedly confessed to killing two additional children who disappeared in the 60s, and whose bodies had never been found.

In 1987, the two killers were taken back to the moors, separately, to help the police to try to find their bodies. Brady found himself back in the media spotlight.

"We stepped onto the moor at dawn. Helicopters and private planes kept circling us and the police seemed determined they would not get any photos. Police kept surrounding me when a low-flying helicopter came at us. Of all hated papers, the Sun got a full-length one, sharp and clear! The moors had changed a lot in my eyes over the 20-odd years that had passed. Many of the changes were real, some imaginary. It was weird seeing the place again, all that space and vastness."

Eventually, the police managed to find the remains of Pauline Reade but, despite many hours of searching, the body of Keith Bennett is still lost on the moors.

Was Brady genuine in his desire to help Winnie Johnson find her son? In his letters to me at the time, he seemed anxious for another chance to go back to Saddleworth and complete the search.

After a second visit to the moors, in the depths of winter, he insisted that he could have found the boy's grave, given more time:

"The convoy reached the moor around 9am. It was five degrees below zero and covered in frost and ice. The police let me lead the way and go to any spots I wished. After an hour, I discovered the junction of streams I had been searching for. I felt relief and exhilaration, and we all stopped for another hot drink and a smoke. As daylight began to fade, I felt a deep instinct that I was close to something important, some aspect I had overlooked. The search area has now been greatly reduced to an area between a sheep pen and a junction of two streams. I felt a great relief and vindication that I had rectified the crucial mistake. I kept underlining that I know beyond doubt that I've found the area. I'd like to see 40 or 50 police searching the area I've pinpointed. Within 48 hours, the instinctive feeling experienced on the moor in fading light became concrete. I was lying on top of the bed in the dark. An image came into my mind. All along I had been searching purely for a triangular site. But now I was seeing something I had forgotten. I saw Myra walking out of the triangle, but when she reached the apex, she did not climb over it but turned to the right into a curved horn of earth which led upwards. I now have the full image of the site vividly in my head. I do not enjoy struggling through sub-zero wasteland, nor being made a spectacle for the media. The police owe me one last visit there. I owe it to the family involved; it is a debt. I have nothing to gain except inner peace, for the media will crucify me whether I succeed or fail."

Police searching Saddleworth Moor for Keith Bennett's body in 1986

Keith Bennett's mother, Winnie Johnson, travelled to the moors many times before her death in 2012, enjoying the peace and solitude.

I went with her on one occasion. Looking out across the bleak moorland, she told me that to be there made her feel close to her lost son.

It was heartbreaking to watch as she waited, year after year, hoping he would be found.

But in the end, the details provided by Brady had not been sufficiently precise to locate the burial place.

Did he really know? Winnie Johnson was convinced that he did. Hindley was clearly hoping the search would advance her campaign for parole, by demonstrating her contrition. Her lawyers would later go to the High Court to challenge the power of the home secretary to keep her locked up indefinitely.

She did all she could to distance herself from the killings, claiming that she had been forced by Brady into becoming his accomplice.

Few people were convinced. The truth is, she had ample opportunity to go to the police and inform on Brady back in the 60s but failed to do so.

The case against her was always damning. She drove the car that she and Brady used to abduct children from the streets, and the vehicle was used to transport them to the moors for burial.

Even back in the 60s, children were warned by their parents not to go off with strangers. But the presence of Hindley in the car with Brady when they stopped to offer the youngsters a lift must have seemed reassuring. A nice young couple, smiling and joking. Nothing to worry about.

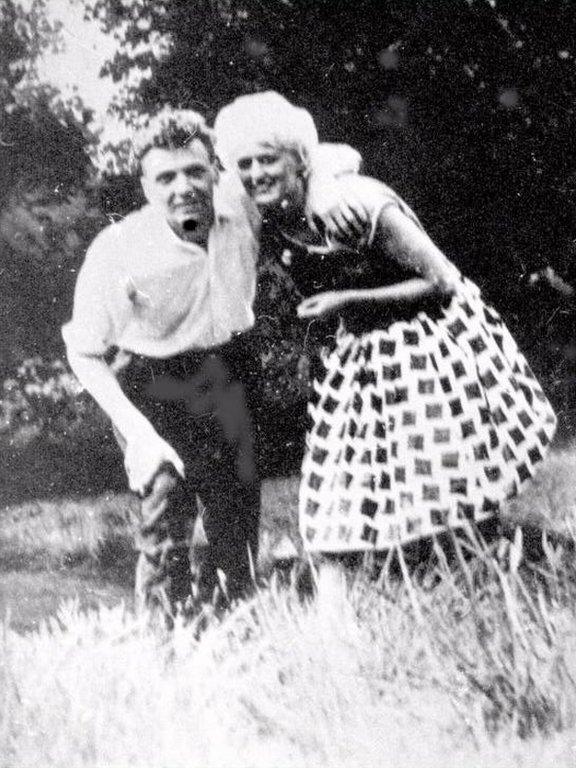

Myra Hindley on the Moors in a photograph taken by Ian Brady

Criminologists have always been fascinated by the dynamics of the relationship between Brady and Hindley. If they had not met would the crimes have happened, committed by Brady alone?

Some have suggested their relationship was a classic folie a deux, a shared psychosis in which a delusional belief is transferred from one person to another.

What is clear is that there was some terrible chemistry, involving sex and sadism, that made it work.

At their trial in 1966, Brady had seemed to be trying to protect Hindley from the full weight of the law. For several years, they wrote to each other from their prison cells. But the more Hindley tried to minimise her role in the killings in an effort to win her freedom, the more resentful he became.

He challenged her claim that she had only taken part in the murders because she was afraid of him. His analysis of their partnership was devastating:

"Myra Hindley and I once loved each other. We were a unified force, not two conflicting entities. The relationship was not based on the delusional concept of folie a deux but on a conscious/subconscious emotional and psychological affinity. She regarded periodic homicides as rituals of reciprocal innervation, marriage ceremonies theoretically binding us ever closer. We experimented with the concept of total possibility. Instead of the requisite Lady Macbeth, I got Messalina. Apart, our futures would have taken radically divergent courses."

For those unfamiliar with ancient history, Messalina became the most powerful woman in the Roman Empire, notorious for her promiscuity, who plotted against her husband, the emperor Claudius.

By casting Hindley in this role, Brady gives a clue to the bitterness he came to feel towards his former lover. He regarded himself and Hindley as equal partners in the murders, but she betrayed him and the secret life they had shared.

He ridiculed her claims that she was an unwilling accomplice:

"Hindley has crafted a Victorian melodrama in which she portrays herself as being forced to murder serially. We both habitually carried revolvers and went for target practice on the moors. If I were mistreating her, she could have shot me dead at any time. For 30 years she said she was acting out of love for me; now she maintains she killed because she hated me - a completely irrational hypothesis. In character, she is essentially a chameleon, adopting whatever camouflage will suit and voicing whatever she believes the individual wishes to hear. She can kill, both in cold blood or in a rage."

Despite my contact with Brady, the families of the murdered children always received me with courtesy and kindness.

Encouraged by my correspondence, some had begun writing to Brady themselves. They saw him as a means of keeping Hindley behind bars.

Like so many others, they could not understand how a woman could have helped to abduct and murder children. And in fact, female serial killers are extremely rare.

So the families of the children, and the man who killed them, came to form a strange alliance. The families also wanted Brady's help in finding the bodies of the children still missing.

I urged him to help the police locate the graves, to allow the families the comfort of a proper burial. The police knew Brady was writing to me but did nothing to hinder the correspondence, perhaps hoping that the letters would reveal useful information.

The detective in charge of the case told me: "He trusts you." Brady himself said he appreciated reporting that was "balanced and unsensational", although I must admit it was sometimes difficult to remain dispassionate.

At around the time he was being taken back to the moors by the police, Brady told me that he was responsible for another five murders, or "happenings" as he called them.

This was tantamount to a confession to a series of hitherto unknown crimes, so I passed the information to the police. With only sketchy details to go on, they were unable to confirm his claims. Did they really happen? Or were they just part of his fantasy world? It was yet another part of the story where the truth would never be known.

The trips back to the moors were the only break from the monotony of Brady's daily life in Ashworth Hospital. But there was always something for him to complain about. In 1999, when he was moved to a new ward, he went on hunger strike.

He recounted his daily existence:

"I've sat in my room, going nowhere, never having exercised in the open air for 25 years, using every available "normal channel" to right matters here these past 15 years, and throughout my 35 years of captivity. I've been taking only sugarless, milk-less tea or coffee, no food. I have no TV or radio and don't read newspapers, though I've been told of some reports. I simply sit writing or reading books most of the time."

When he continued to refuse food, the doctors fed him against his wishes, through a nasal tube. So he went to court, hoping to establish a legal right to end his life.

In 2000, a hearing was held in Liverpool, behind closed doors. The tight security meant that the waiting media did not even get a glimpse of him as he enjoyed his day in court. But he got his story out.

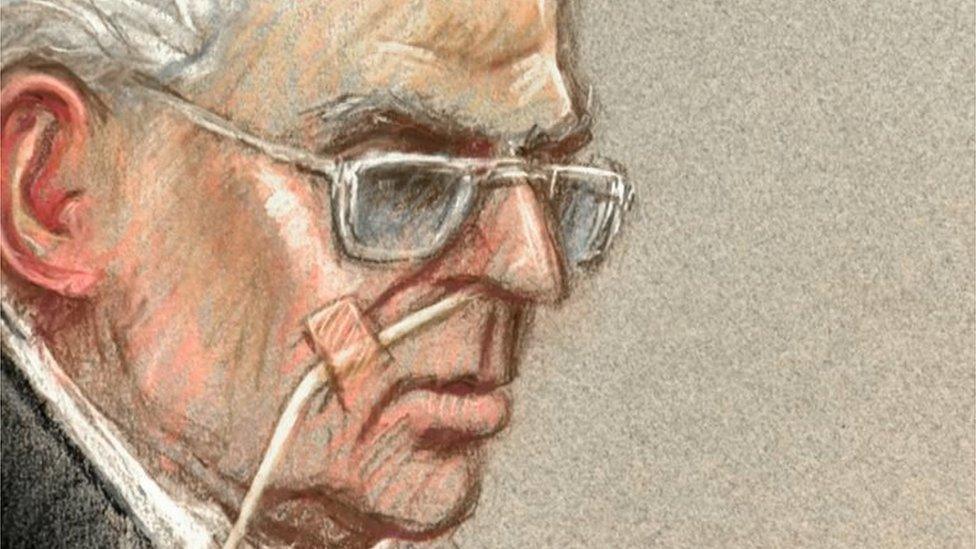

Brady was taken to Liverpool Crown Court for his 2000 right-to-die hearing

Knowing the hearing would be held in private, he had sent me a 5,000-word document, setting out his case.

Once again, Brady was the centre of attention, taking on the system. But his arguments failed to convince the judge, and the hospital was told it could continue to feed him, to keep him alive.

Then in 2013, Brady finally got the public platform he craved. The media were able to observe him via a television relay as he gave evidence to a mental health tribunal at Ashworth.

The picture that emerged was of a man who was paranoid and narcissistic. He wanted to be sent back to prison, where he might have been able to complete his hunger strike without medical intervention.

Brady seemed to relish the occasion. He was back in the spotlight, back in the headlines. But once again the decision went against him. The panel ruled that he was mentally ill, and would have to remain in a secure hospital where his condition could be treated.

Court sketch of Brady appearing at a mental health tribunal in 2013

During the hearing, Brady refused to answer a direct question about whether he would in fact kill himself if was sent back to prison.

In his letters to me, however, he said his life had become meaningless and all he wanted was the opportunity to bring it to an end:

"I have had enough. My objective is to die and release myself from this once and for all. I am not interested in being kept alive artificially by force feeding. My death strike is rational and pragmatic. I am eager to leave this cesspit in a coffin."

Brady considered himself to possess superior intelligence. He found it difficult being surrounded by other patients who were all mentally ill, rather than being able to mix with the diverse characters he had encountered in the penal system:

"In prison I had intelligent company - train robbers, IRA and Arab terrorists, financiers, counterfeiters, gun-runners, drug lords, East End gangsters, ex-government ministers. I played John Stonehouse in the chess final at Wormwood Scrubs. Having spent the past years in the company of criminals and madmen, I have a very unusual circle of friends out there in the free world."

Did Brady ever look back over his life and contemplate how things might have been different?

A few years ago, he let me see a letter he had written to his mother. To my surprise, it was a wistful memoir of the happy times they had spent together in his youth.

It described in lyrical terms holidays spent in the Scottish Highlands, the sentiments quite at odds with his reputation as a tough kid from the Gorbals:

"When I close my eyes, I re-live childhood holidays in fascinating detail, many forgotten memories surfacing. Remember the low ceilings and oil lamps in the whitewashed Dunning cottage and the late-night cups of Oxo? The honking geese in the courtyard of the farm we stayed at in Tobermory? The red deer standing in the deep green gloom of the deciduous forest; the wildcat I surprised in the high heather hills behind the farm; the wooden bridge in the meadow beside the farm? Naturally I also bring to mind all the other holidays. The many tours up to Scotland by car, the vast spaces and bracing air of the Highlands... enough."

Enough, says Brady. After giving us a tantalising glimpse of happy days during his childhood, he firmly closes the door to the past. He ends the letter with a request to his mother to send me a copy.

She was then aged about 90 and living in relative anonymity in Longsight, near the centre of Manchester. Surprisingly, perhaps, she never moved away from the city where her son committed his dreadful crimes.

This unexpected glimpse into their life together was startling. Stories about Brady's childhood had painted a picture of a troubled boy who had grown up in a single-parent home, never knowing his real father.

As Brady acknowledged himself, the reality of his childhood years seemed to contradict a widely-held view about the roots of violent crime, especially sexual crime:

"It is fashionable nowadays to blame one's faults on abuse as a child. I had a happy childhood."

Why had Brady wanted me to see the letter to his mother? Was he trying to show he was a man with human emotions like everyone else? It inevitably prompts the question of how someone capable of such feelings could become a cold-blooded predator who enticed children away from their homes and families, and then killed them with his bare hands.

Saddleworth Moor

The happy childhood did not last. As a delinquent youth, Brady got into scrapes with the law, before finding a job as an office clerk. It appeared to offer reasonable prospects, and perhaps the hope of a decent life. But fate took a hand.

Working in the same office was a young typist called Myra Hindley. We will never know if things might have been different had they not met, but together they were deadly.

Perhaps it was memories of his childhood holidays that drew him to the bleak moorland above Manchester. Just as the Scottish Highlands may have been a welcome relief from the tenements of Glasgow, so the empty landscape of Saddleworth may have offered an escape from the terraced houses and factories of industrial Manchester.

Judging by the snapshots Brady took of himself and Hindley on the moors, it was somewhere that he felt happy.

But it was also a place made special by the terrible secrets it held, secrets that bound the two of them together.

Seeing them posing for the camera, they look like any other young couple who are in love. Until you realise that they include a shot of Hindley standing on the grave of one of their victims.

This was the woman who would later claim that she was Brady's unwilling accomplice. The photographs, and a horrific tape recording of their victim Lesley Ann Downey, tell a different story.

Given his love of open spaces, how much of a punishment was it for Brady to be confined within the walls of a prison or a high security hospital for so many years?

At Ashworth, he refused his right to take exercise in the open air for many years. Another contradiction.

Our lengthy correspondence has finally been ended by his death. It is easy to dismiss Brady as an evil monster, who does not deserve an ounce of pity.

I have met the families of the children he killed, and seen how he shattered so many lives. They spent years living with the consequences of his crimes. As the mother of Lesley Ann Downey once told me, the families are the ones serving a life sentence.

Lesley Ann Downey

For nearly 50 years, Brady tormented them. His own life was effectively over when he was convicted at the age of just 28.

It was only the abolition of the death penalty just before his trial that saved him from the hangman's noose. He survived, but it turned out to be a living death.

I am left with a box full of letters, but I am still little the wiser about what drove him to kill.

Ian Brady has finally gone to his grave, having found the death he craved for so long. Many of his secrets have gone with him. He remains the personification of dark forces that we struggle to understand.