The DNA detective helping to reunite families

- Published

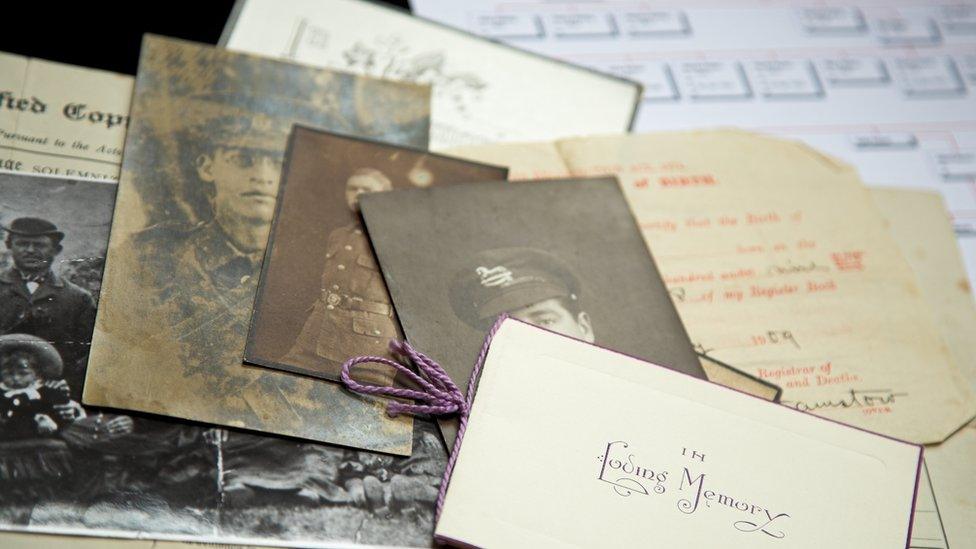

Julia Bell has no genetics background but has an extensive knowledge of how to analyse data

A man left abandoned as a baby in a cinema toilet 61 years ago has tracked down his siblings with the help of a so-called "DNA detective". But what do they do?

"There's an analogy I like to use: I can crack any safe, some will just take longer than others," Julia Bell tells the Victoria Derbyshire programme.

She helps people - many of whom have no knowledge of who their parents or siblings are - track down their long-lost relatives.

Julia recently helped Robert Weston, who was found in a ladies toilet in an Odeon cinema in Birmingham in 1956, find his half-brothers and sister for the first time.

Many of her cases involve American soldiers, or GIs, who were stationed in the UK during World War Two, she says.

Indeed, Julia says she is approached by someone who has discovered their father was in fact an American GI about once a month.

"More children were fathered by American servicemen than many people imagine," she says.

Julia is also currently helping a woman who, as a baby, was left in a box at London's Kings Cross railway station, while another case involves a baby left on a train in 1928.

So how does it work?

'Searching for 44 years'

"It starts with a spit test, a DNA test, which I get people to do," Julia says. "That's sent away for testing."

She then uses uses three direct-to-consumer DNA databases to cross-reference the data and then the detective work begins.

Julia - who currently is not charging clients - says she begins looking at patterns within the database to try and establish matches.

She then uses contacts around the world to try to identify relatives - however distant they may be.

Tommy Chalmers (left), Pat McBain (centre) and Robert Weston (right) outside the house where their father lived

When Robert Weston contacted her - 61 years after being abandoned in a cinema - he said he "had been searching for a long, long time - 44 years or so" without success.

Julia asked him to provide a DNA saliva test and searched on the database in the hope of finding a distant relative.

"There will be somebody on there - fourth cousins or something - for nearly everyone out there," she explains.

Initially there were more distant matches, but Julia was able to find and test a second cousin.

"I asked her if she had any male cousins and she said 'Tommy'," Robert explains. "He agreed to be tested and he turned out to be my half-brother."

But he says: "You need a huge dollop of luck with all this."

The Birmingham Evening Despatch carried the story of Robert being found on its front page in 1956

On occasion, it is possible to trace relatives even further back.

The Salvation Army's family tracing service has reunited relatives who have been out of touch for more than 80 years.

It says it reunites 10 people every single working day, with an 89% success rate.

It also protects the privacy of the person being sought by promising it will not pass on personal details unless permission is granted.

Julia says while most cases can eventually be solved, a small number will permanently draw a blank.

Even then, she says a person can get some information, including an estimate about their ethnicity. But she says as DNA databases increase in size, the odds of closer matches get better all the time.

'Very sensitive cases'

Julia has no genetics background, saying you instead need to be "smart and logical" and know how to work with data.

"I have a knowledge of science but my background was in teaching in Singapore," she says.

"My mother didn't know who her father was and that's how I got into this, helping to look for her dad."

She adds: "I found someone in the states [US] who works in ancestry who helped show me how to do this.

"She helped me with seeing the patterns and using my intuition. She put the pieces together and I realised I was good at this.

"[My mum] found her father had died four years earlier. But she had a sister and now she's in touch with her family in the south of the US."

Where there is a success, she says third parties are "generally" positive when they find out they have relatives they never knew - although cases of abandoned babies can be "very sensitive".

"I might not always be the one to break the news, sometimes it could be a social worker."

A running theme, however, is that many long-lost relatives - despite their different upbringings - often share habits or interests.

"One set of people I matched turned out to both be astrophysicists," she says.

Robert Weston and his half-bother Tommy share the same sense of humour, she adds.

"It's like they've known each other their whole life."

Watch the Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

- Published17 May 2017