Secret German peacemaker in Northern Ireland's Troubles

- Published

Eberhard Spiecker's secret peace negotiations went back to the 1970s

Eberhard Spiecker remains an enigma in Northern Ireland's peace process.

He died in Germany in May and much of his far-reaching involvement in the labyrinthine politics of the Troubles is likely to go with him to the grave.

His work stretched over several decades, almost entirely unseen, holding meetings between people who refused to meet in public and exchanging messages between people who could deny that they had ever been in contact.

It seems to have included two undisclosed IRA ceasefires and three peace talks, only one of which has ever been fully revealed.

If you find a public reference to Dr Spiecker, it's usually as a "shadowy clergyman", who staged secret peace talks in Duisburg, in the old West Germany, in 1988 between deadlocked unionist and nationalist parties.

The outsider

This was seen as a symbolically important piece of bridge building across the political permafrost - but it also seemed a strangely isolated event.

Who was this German Lutheran who had pulled off such an unlikely meeting between representatives of the DUP, the UUP and the SDLP with a go-between for Sinn Fein, a decade before the Good Friday Agreement?

What is now apparent is that this was far from a one-off involvement.

Dr Spiecker, born in Duisburg in the last days of the Weimar Republic, had been involved in peace initiatives in Northern Ireland since the early 1970s.

Following a meeting of senior Northern Irish Catholic and Protestant church leaders in Germany, Dr Spiecker was given the role of building contacts in Northern Ireland, in an attempt to resolve the conflict and loss of life.

He was an outsider, a neutral figure, who tapped into a network of religious leaders working across Northern Ireland's divide.

Among his early contacts was Canon Bill Arlow, a Church of Ireland minister who controversially arranged a secret meeting between Protestant church representatives and IRA leaders in 1974, with the aim of establishing a ceasefire.

This meeting ended when the location was raided by the Irish police.

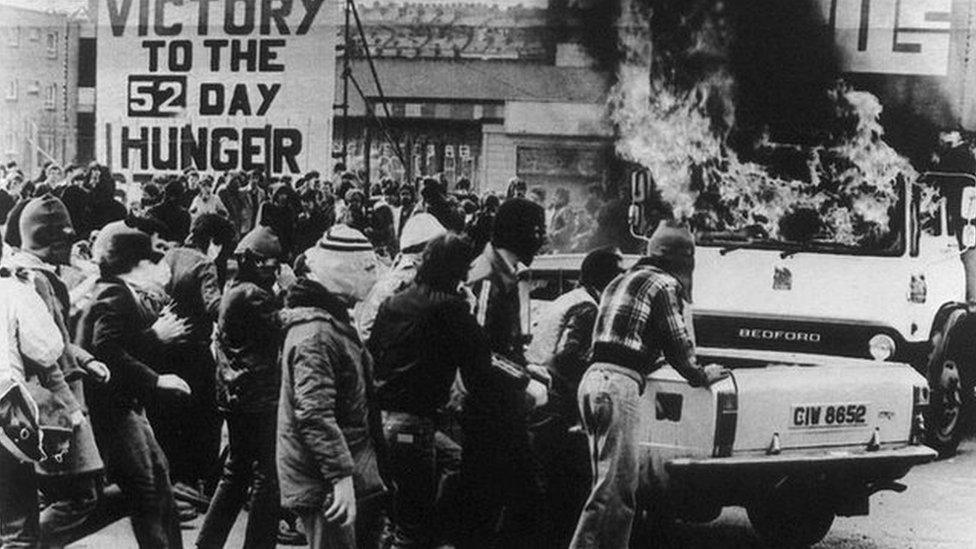

During the republican hunger strikes of 1980 and 1981, Dr Spiecker put together a plan to reverse out of the impasse, with contacts that included the Archbishop of Canterbury, Robert Runcie, the head of the Catholic church in Ireland, Cardinal Tomas O'Fiaich, Irish prime minister Garret FitzGerald and Gaston Thorn, president of the EU Commission.

Secret meetings in Germany

This was unsuccessful - and Dr Spiecker, writing a few months before his death, said the hunger strikes left a huge "chasm".

His response was to try to build an understanding between politicians across the sectarian divide - through secret meetings held in Germany, which would move from trust building to concrete proposals.

He described a "relaxed meeting" between unionists and nationalists in the town of Boppard on the Rhine in 1985.

The hunger strikes left a political "chasm" that Dr Spiecker wanted to bridge

It was designed to be convivial and away from the violent backdrop of Northern Ireland, where even admitting to such meetings would have been politically impossible.

Later in the same year the signing of the Anglo-Irish Agreement between Margaret Thatcher and Mr FitzGerald prompted a mass resignation of unionist MPs.

Dr Spiecker said that at his private talks in Germany the "rapprochement was successful".

There were more undisclosed cross-party talks in May 1987, bringing together politicians from the Ulster Unionist Party, Social and Democratic Labour Party and the Alliance Party.

Dr Spiecker brought opposing sides away from the violence to talk secretly in Duisburg

This meeting took place in Essen in a Catholic seminary where Pope John Paul II had stayed a couple of weeks before.

"The participants were no longer only well-known personalities, but also representatives of political and social life," wrote Dr Spiecker.

"As an example, Martin Smyth can be mentioned, the then Grand Master of the Orange Order, who probably took part in negotiations in the rooms of a Catholic seminary for the first time."

Organisers of the Essen meeting identified another very prominent unionist politician who attended.

Building bridges

The talks focused on familiar territory for Northern Irish negotiations - the possible shape of self-government, the roles of the Westminster and Dublin governments, responsibility and cross-community support for policing and the engagement in talks of Sinn Fein.

Further talks followed the next year in a hotel in Duisburg - with Peter Robinson from the DUP joining Austin Currie from the SDLP and representatives of the UUP and Alliance.

Dr Spiecker (right), a campaigner for links between churches, in a meeting with Joseph Ratzinger, later Pope Benedict

And significantly they were joined by Father Alec Reid, a priest who acted as a go-between with the "republican movement".

"Eberhard Spiecker's special qualities were shown," according to assistants in Germany who were at the talks.

"He brought people together who, until then, had never sat around one table. He succeeded in getting these people to work on the resolution of the conflict in a constructive and convinced way, in spite of all the differences."

Even if in secret, politicians were engaging with each other - and a door was being opened to Sinn Fein, if there was an end to violence.

"The 1988 talks were significant and part of the 'bridge building' process," says Peter Taylor, documentary maker and author who followed the inside story of the peace process.

"They were around the time of the Hume/Adams talks facilitated by Father Alec Reid of the Clonard Monastery in Belfast. Those talks helped build the ideological platform for the declaration that Britain had no 'selfish or strategic interest' in Northern Ireland."

German ceasefire

While the talks in Boppard and Essen remained confidential, the Duisburg meeting was leaked - making international headline news in 1989.

According to the team in Germany who put together the talks, this breach of confidentiality, and the exposure of such secret exchanges, was the "end of the matter" for this strand of negotiations.

Dr Spiecker put forward unionist and nationalist contacts during the Drumcree stand-off

But Dr Spiecker's work continued - this time in his own country.

He held talks with leading republicans, regarding a wave of lethal attacks on British military personnel based in Germany.

According to Dr Spiecker's assistants, an agreement for an IRA ceasefire was reached in 1990, specific to Germany. This was a "Waffenstillstand" or "weapons stand still".

IRA activity moved to neighbouring countries, with the Netherlands being mentioned, before a ceasefire for mainland Europe was agreed two years later.

Although these localised ceasefires would later be breached, these suspensions of violence were seen as part of the "confidence building" during wider negotiations.

No records

But is there any evidence for such ceasefires?

There are sources, close to the peace process, who say they have heard rumours of such unpublicised ceasefires.

Tony Blair responding to the IRA ceasefire in July 1997

There are unlikely to be any official records - and more risks than reward for any of the participating parties to talk about such controversial deals.

Another interpretation has been that a "ceasefire" could have been a cover for what was a forced withdrawal after a failed terror campaign.

Ed Moloney, author and historian of the Troubles and the peace process, says he had "heard about the German and European ceasefires, but not whether Spiecker was involved".

He says the deal had to be approved by the German authorities.

But the German government's political archive says there are no records of such an exchange.

It would not have been unheard of, because in later secret exchanges between Sinn Fein and the British government, ahead of the 1994 IRA ceasefire, there were references to unpublicised temporary suspensions in violence.

But there is more speculation than certainty about such events and more long silences than explanations.

'Back channel' secret contacts

Another curiosity is that Dr Spiecker - invariably recorded as a "clergyman" - was not actually a religious minister.

He was an elder in the Lutheran church and chaired church committees, and deeply involved in ecumenical causes, but by profession he was a lawyer.

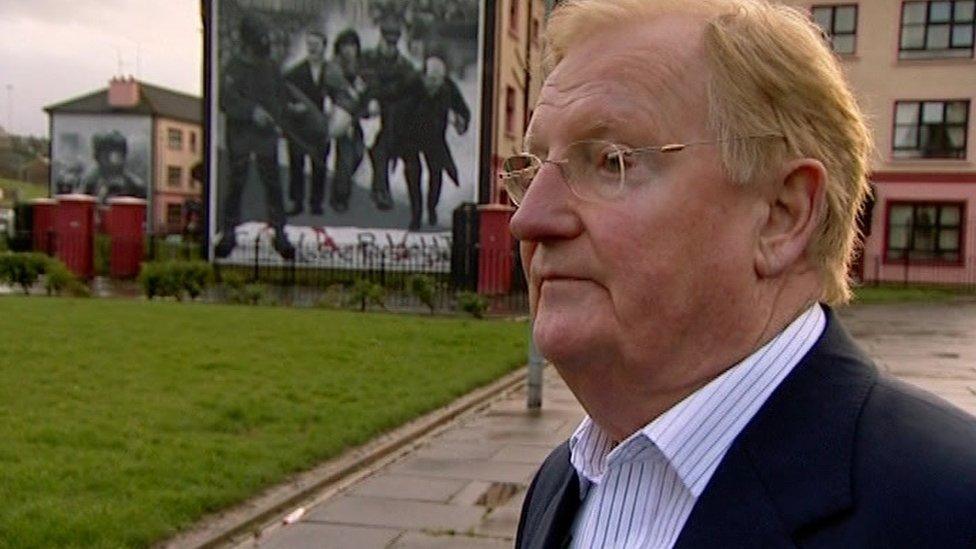

Brendan Duddy, the contact between the British government and the IRA, was also in communication with Dr Spiecker

Dr Spiecker's role might raise other questions.

He acted in secret - and was valued for his unshowy trustworthiness - but his work seems to have overlapped with other "secret peacemakers".

Brendan Duddy, who died recently, was the secret "back channel" contact between the IRA and the British government, from the 1970s to the 1990s.

In Mr Duddy's archive of letters there are references to faxes he exchanged with Dr Spiecker.

There were messages from 1997 exchanged about defusing the violent stand-off over the Orange Order march at Drumcree, with Dr Spiecker putting forward representatives of unionists and republicans for talks, with the offer of hosting negotiations in Germany.

There were also confidential messages to the former Irish prime minister, Albert Reynolds, before a round of peace process negotiations in 1997. Dr Spiecker set out unresolved areas for an IRA ceasefire, such as policing, decommissioning of weapons and prisoner release.

He seemed to have had access across the landscape of Northern Ireland politics, meeting with unionists Peter Robinson, Jim Molyneaux and Martin Smyth; the SDLP's John Hume and Austin Currie and senior figures from Sinn Fein.

Christmas prayer and truces

How much official support was there in the background for his undertakings? How were his freelance efforts linked to wider negotiations?

His assistants remember a man of deep conviction whose "absolute discretion enabled people and groups to trust him".

Ian Paisley and Martin McGuinness became symbols of the power sharing agreement

They describe his part in Christmas truces.

"Eberhard was often involved in bringing about ceasefires on Christmas Eve.

"He would come to eat with us that day, then we would go to church and the rest of the day was spent on the phone or by his fax machine in communication with various places."

Those "various places" are likely to remain unknown.

This was a lifetime spent getting distrustful opponents to talk to each other, working out of sight to stop the murderous violence.

With his death, more of the secret efforts of this German peacemaker are being revealed.

- Published15 May 2017