London attack: What we have learned

- Published

Run, Hide: Police used prepared tactic to clear area

Three terror attacks on the UK in 75 days. Thirty-four people dead, many, many more injured. The five attackers all dead too.

By my calculations, this is the most sustained and bloody series of attacks outside of Northern Ireland since the IRA's 1974 winter bombing campaign - although there have been bigger individual attacks, such as the 7/7 London bombings in 2005.

While the motive and aim has been the same, each appalling incident has differed significantly from the last.

These differences reveal the challenges faced by the security services in intercepting them before it is too late.

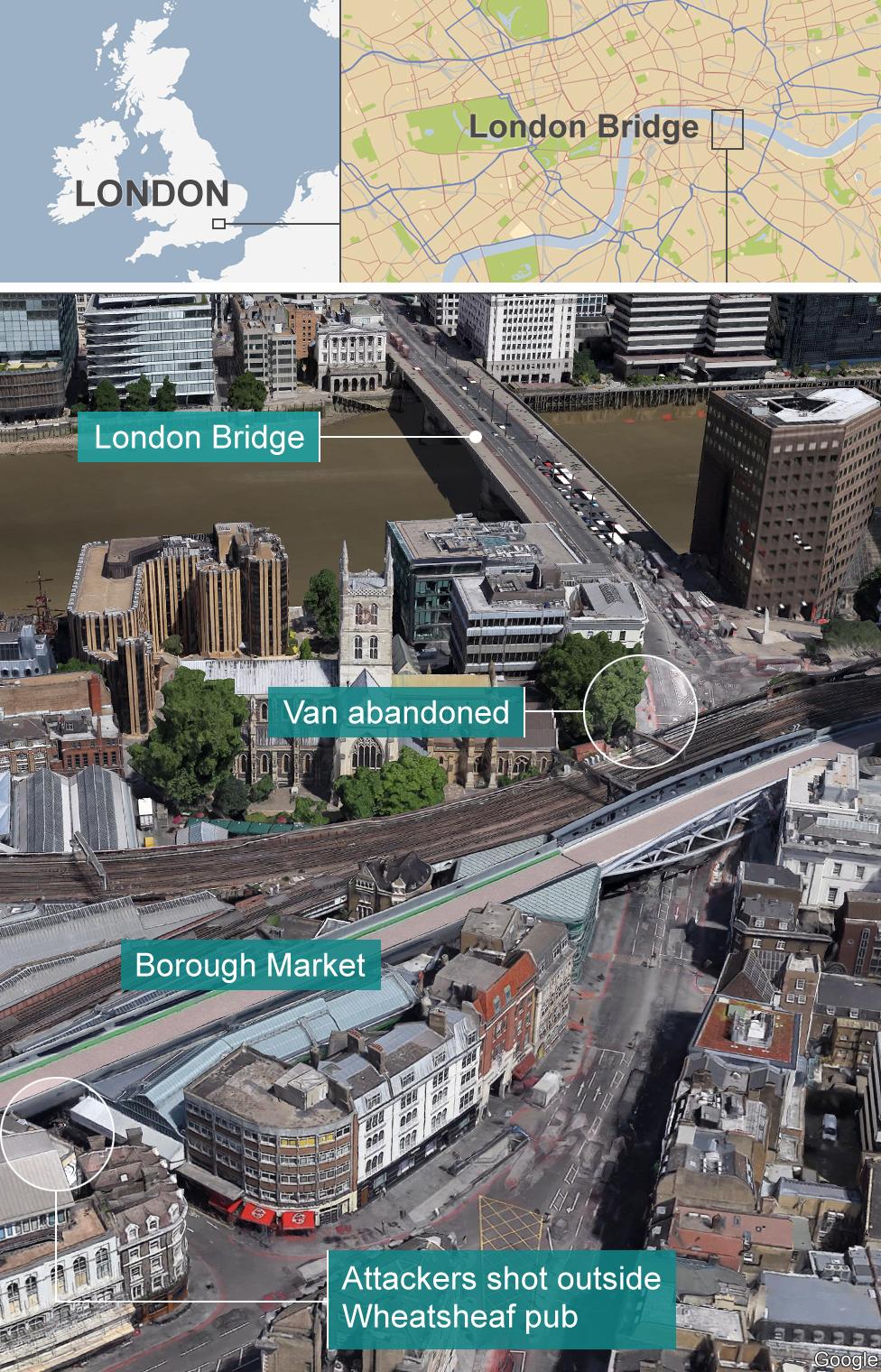

What we know so far: The facts of the attack

The Khalid Masood Westminster attack was the act of a man acting alone. His target was not only people around Westminster, but those inside Parliament's grounds too.

Then, last month in Manchester we had another lone attacker. His target was entirely different: not a high-profile government building, but kids on a night out.

This weekend's attack in London was quite different again: this time, three men acting together. They eschewed well-secured public places and targeted an obvious crowded area.

Both bridge attacks shared a methodology that's been repeatedly promoted by jihadist groups like the self-styled Islamic State/Daesh: a vehicle to knock people over and knives once on foot.

This is not new - it was how Fusilier Lee Rigby was murdered four years ago.

Approximately half of the 18 foiled plots since 2013 - some of which we cannot currently report for legal reasons - have involved some combination of these techniques.

Police spend a lot of time trying to work out whether they can spot people involved in "hostile reconnaissance" - observing places they want to attack.

So a priority for the investigation will be to establish whether the three men carried out any such planning - or did they simply make it up as they went along on the night: looking for crowds, looking for targets.

Lone attackers can be harder to stop than groups of attackers because, quite simply, they can keep their plans in their head.

But groups make mistakes.

It's hard for them to avoid detection thanks to a combination of factors, including the time it takes to organise themselves, tip-offs from a worried neighbour and the computing power of modern eavesdropping.

So how did these men manage to plan without being noticed?

We've also learnt that the routes to choosing extreme violence can be quite different.

The Westminster Bridge attacker once appeared on the fringes of another investigation, but he had been dormant for many years. What was the trigger for him to attack, given he was acting alone?

Manchester bomber Salman Abedi was different. His route to extremism appears to be intertwined with the very complex revolutionary Islamist politics of Libya.

We know very little about the London bridge attackers so far. At least one of the men, whom we are not naming at this stage, once associated with one of the most notorious groups ever seen in the UK.

This is perhaps the least surprising route to radicalisation of all three attackers. The group has been partly broken up. But did a latent threat from one of its occasional followers go unnoticed?

"Get down" - police enter bar at London Bridge

The security service, which was apparently alerted to the Manchester bomber's extremist views three times, is already examining how it dealt with those warnings - but did it miss something in this case too?

Two final things we have learned.

Eyewitness have told how the police relied upon a tactic to protect the public in the event of a marauding attack.

Officers tried to rapidly clear the area by telling people to "run" to a safe area. Those they could not safely move - people in restaurants and bars - were told to "hide".

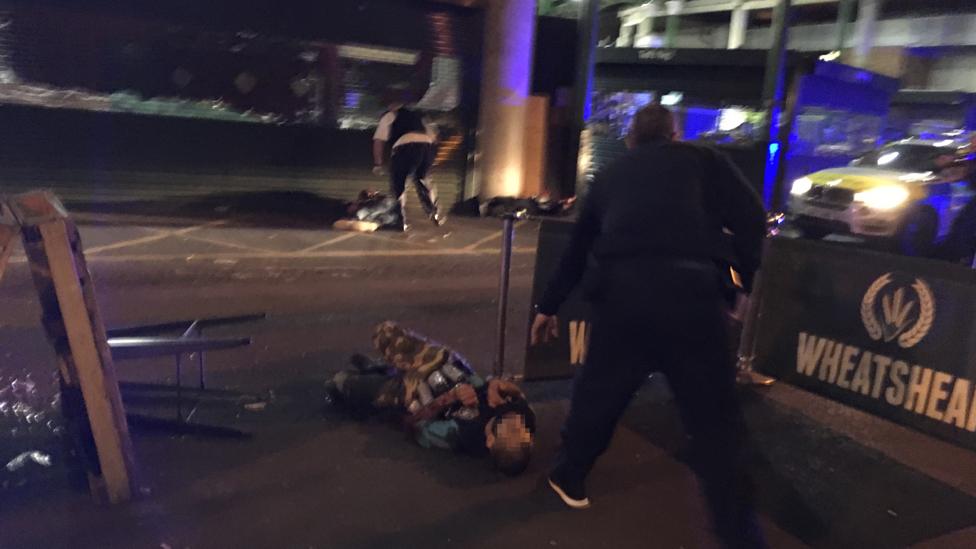

One of the attackers who was shot

Eight minutes after the first 999 call, the killers, wearing what looked like suicide bombs, had been gunned down by specialist officers who fired 50 rounds.

That is almost half the time it took an armed team to reach Fusilier Lee Rigby's killers in 2013.

The final issue that may now come to the fore is politics. Since 2001, the range and scope of counter-terrorism powers has expanded considerably.

In her Sunday statement, the Prime Minister talked about "enough is enough".

It had echoes of Tony Blair's famous speech, external following the 7/7 bombings in which he said the "rules of the game had changed".

Prime Minister Theresa May: "Enough is enough'

He promised a range of powers to deal not just with violence extremism, but those he said provided it with an ideological breeding ground.

His government ultimately found some of the measures legally too difficult to implement.

Theresa May has talked on and off since 2015 about measures to combat those who "reject our values" - but legislation hasn't yet appeared.