Obituary: Sqn Ldr George 'Johnny' Johnson

- Published

"Johnny" Johnson was the last survivor of the RAF bomber squadron known as the Dambusters.

In May 1943, three formations of Lancaster bombers were sent to attack a series of dams in Germany's industrial heartland.

Their targets provided Hitler's war machine with hydro-electric power and water for steel production. They were well protected, with anti-aircraft guns and torpedo nets.

The RAF's 617 squadron carried specially-developed "bouncing bombs" devised by the inventor Barnes Wallis. They were designed to skip over the dams' defences and explode against the sides.

Two targets - the Möhne and the Eder dams - were destroyed, causing 1,600 casualties and catastrophic flooding which hampered the German war effort. A third - the Sorpe - was badly damaged.

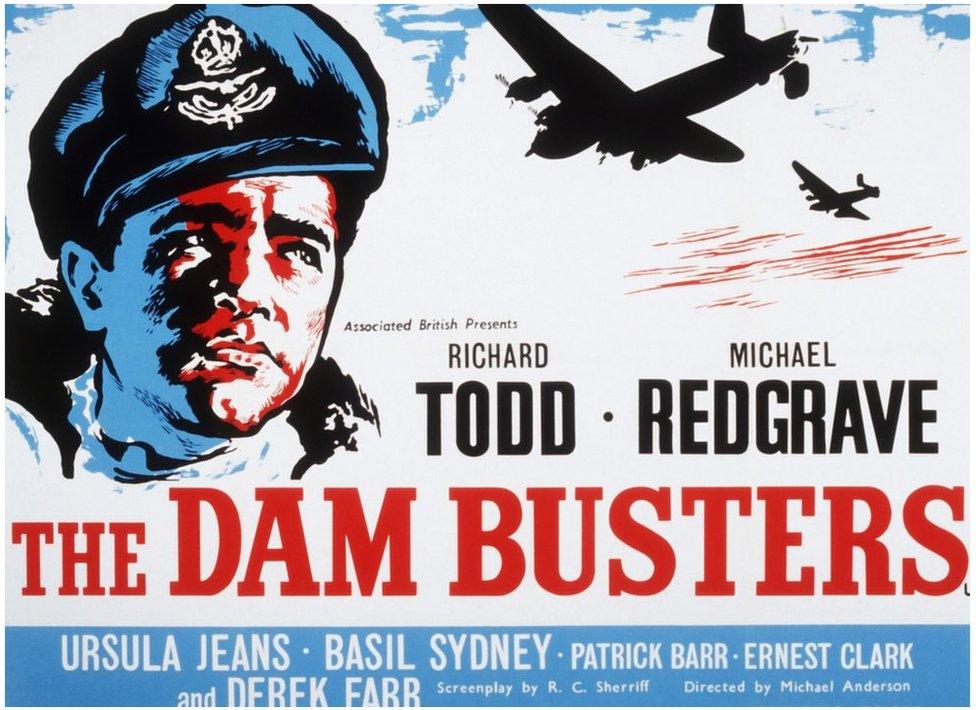

"Johnny Johnson" and the men of 617 Squadron were immortalised in the 1955 film The Dam Busters

The raid was immortalised in the 1955 film The Dam Busters starring Richard Todd and Michael Redgrave. The film's theme music is still sung at football matches and has even been used in beer commercials.

But 617 Squadron paid dearly for its bravery. Eight of the 19 planes involved were shot down, and 53 men lost their lives.

The last Dambuster

George Leonard Johnson was born in Lincolnshire on 25 November 1921.

The sixth and youngest child of a farm worker, his mother died when he was still a toddler. Leonard - as he was known within the family - was cared for by an older sister, and roughly beaten by his father.

Johnson suffered physical abuse from his father after his mother died

Johnson was sent to Lord Wandsworth's Agricultural College in Hampshire, a boarding school that offered free education to farming children who had lost a parent. The local squire's wife eventually persuaded his father to let him go.

After school, he worked as a trainee parks superintendent in Basingstoke. In 1940, he volunteered for service in the RAF.

Joining the RAF

A year later, Johnson - now known to all as "Johnny" - was sent to Florida for pilot training. He failed the course and developed a deep dislike for the US Army Air Corps, which he thought obsessed with petty discipline and incapable of marching properly.

Back in Britain, he opted to become a gunner until he discovered that bomb aimers got higher wages. He joined No. 97 Squadron where his team was piloted by a New Yorker, Joe McCarthy.

Despite his reservations about Americans, Johnson greatly admired McCarthy - describing him as "big in size, big in personality and big in pilot ability".

"Johnny" Johnson volunteered for the RAF in 1940

McCarthy's crew transferred to 617 Squadron in March 1943, when it was formed under 24-year-old Guy Gibson.

Johnson described his new Wing Commander as "arrogant, bombastic, a strict disciplinarian, but one of the best pilots in Bomber Command".

All leave had been cancelled as 617 Squadron prepared for Operation Chastise, the raid on the German dams. Due to get married, Johnson pleaded for a few days off, and Gibson eventually relented.

Bouncing bombs

To destroy the dams, Barnes Wallis had first considered a 10,000 kg bomb dropped from a height of 40,000 feet - but no aircraft was capable of flying at such a height with so heavy a payload.

Instead, he had devised a kind of depth charge - dropped at a height of 60 feet at 240 mph - that would bounce over the torpedo nets and explode next to the wall of the dam.

In order to carry the weapons, much of the Lancaster's armour had to be removed. The weapons, too big to fit into the bomb bay, were carried underneath and set spinning before their release.

Johnson took part in intensive trials over British reservoirs and Chesil Beach. Realising that the Lancaster's altimeter was not accurate enough, spotlights were installed at each end of the aircraft - with the beams intersecting at exactly 60 feet.

'Johnny' Johnson married Gwyneth Morgan less than a month before the Dambusters raid

The toughest target

Johnson and McCarthy were briefed to attack the Sorpe Dam, just east of Dortmund.

It was the toughest target of all. The Sorpe - unlike the Möhne and the Eder dams - was constructed of concrete covered by thousands of tons of earth.

Like the rest of 617 Squadron, Johnson had practised releasing his bomb flying directly at the target. On the afternoon before the raid, however, he was told that wouldn't work for the Sorpe.

Instead, McCarthy would have to fly parallel across the dam at a low level. The specialist bomb-aiming equipment developed for the raid was now useless, and Johnson was going to have to rely on instinct to drop the bomb dead centre.

"Johnny" Johnson (far left) and his Dambusters crew

Of the five Lancasters which set off for the Sorpe dam, only two made it to Germany.

When they arrived, McCarthy realised the approach was even more hazardous than expected. A church steeple on a hill overlooking the dam meant he had to pull up sharply.

In a BBC interview in 2014, Johnson told how it took nine practice runs - amid complaints from the rear gunner - before he was confident enough to release the bomb.

"On the 10th run we were down to 30ft," he recalled. "When I said, 'Bomb gone,' 'Thank Christ!' came from the rear turret."

"We pulled up to stop hitting the hills on the other side," Johnson explained, "so I didn't see the explosion, but Dave did in the rear turret - and he estimated the tower of water went up about 1,000ft."

'Not only that," he added, "in the down flow, some came into the turret so I thought I was going to be drowned.'"

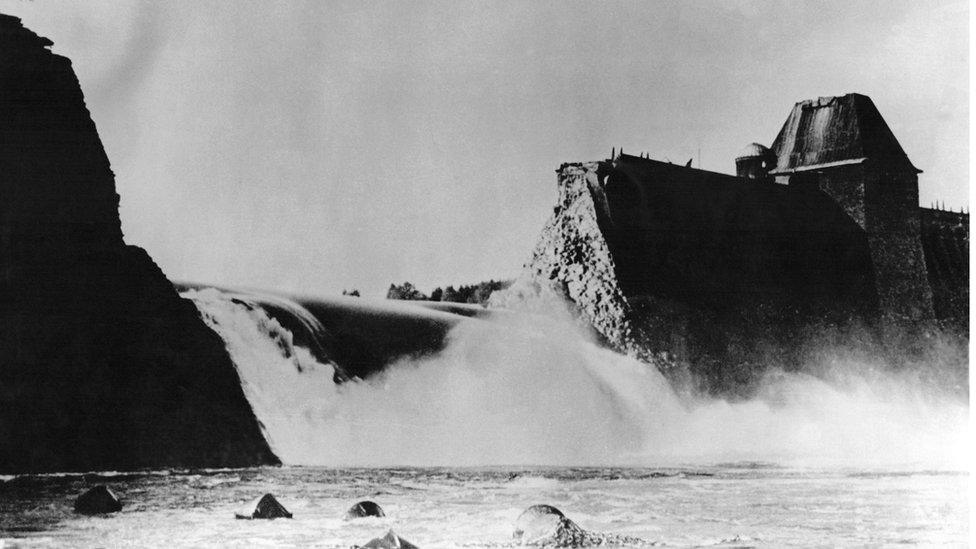

The Möhne dam photographed after the Dambusters raid

Honoured

The Sorpe dam was damaged, but not breached. The Möhne and the Eder, however, were completely destroyed.

"Johnny" Johnson went to Buckingham Palace to receive the Distinguished Flying Medal for his bravery. He flew another 19 missions with 617 Squadron, until his wife became pregnant and McCarthy insisted he was reassigned.

Later he was commissioned, qualified as a navigator, and stayed in the RAF until 1962 - retiring as a squadron leader.

Johnson retrained as a teacher - first with primary school children and then psychiatric patients at the high-security Rampton hospital.

He became a local councillor and chairman of the Torquay Conservative Association.

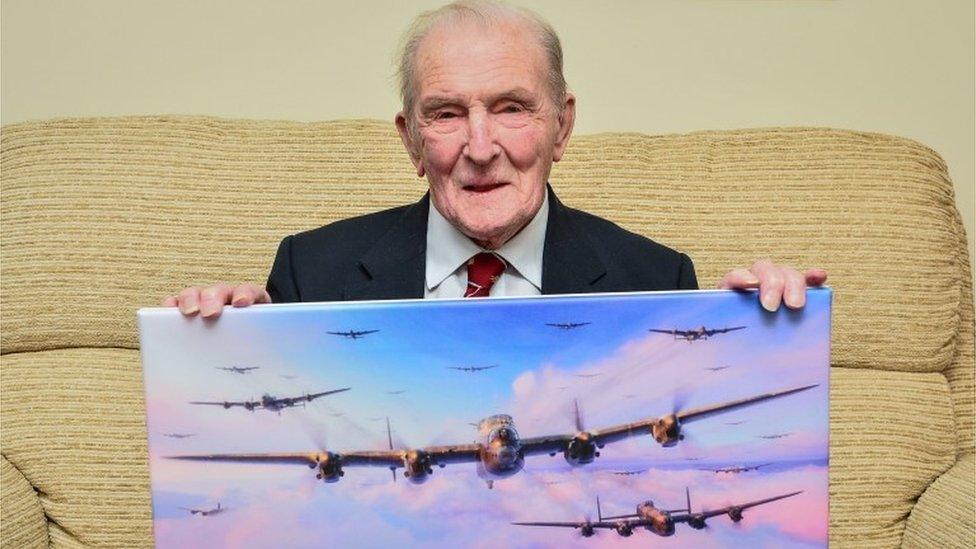

"Johnny" Johnson shares his memories of the dambusters raid with John Butcher, the Commanding Officer of 617 Squadron, in 2017

As the last survivor of the raid, there were periodic campaigns to award him a knighthood.

The most recent saw a 237,000-signature petition handed to No. 10 Downing Street by the TV presenter Carol Vorderman and Gulf War veteran John Nichol in 2017.

Had it come, "Johnny" Johnson planned to ask Her Majesty "with due humility" if it could be dedicated to the 55,573 bomber air crews that gave their lives during the war.

Johnson often shared his memories of the raid as a means of paying tribute to those who were killed

He was awarded an MBE in that year's Birthday Honours. Three years later, he celebrated his 100th birthday.

"A great raid"

Sir Arthur Harris, the head of Bomber Command, was known to have regretted the mission. With a casualty rate of 40%, it was - he believed - a waste of men and resources.

Others disagreed. From the Möhne dam, a 10m high tidal wave had swept through factories, power stations and mines - with a real impact on Germany's military capability.

"That night," wrote Hitler's confidante Albert Speer, "employing just a few bombers, the British came close to a success which would have been greater than anything they had achieved hitherto with a commitment of thousands of bombers."

On anniversaries of the raid, Johnson was willing to share his memories - as a means of paying tribute to his fallen colleagues.

"I was lucky with the right crew, in the right place at the right time," he said. "I think it was a great raid, and a tribute to all those who took part - particularly those who gave their lives in pursuing their target".