Grenfell Tower: A shadow over the capital

- Published

Drive over London's Westway, and Grenfell Tower demands your attention. It is a black nail that has been hammered into the nation's conscience.

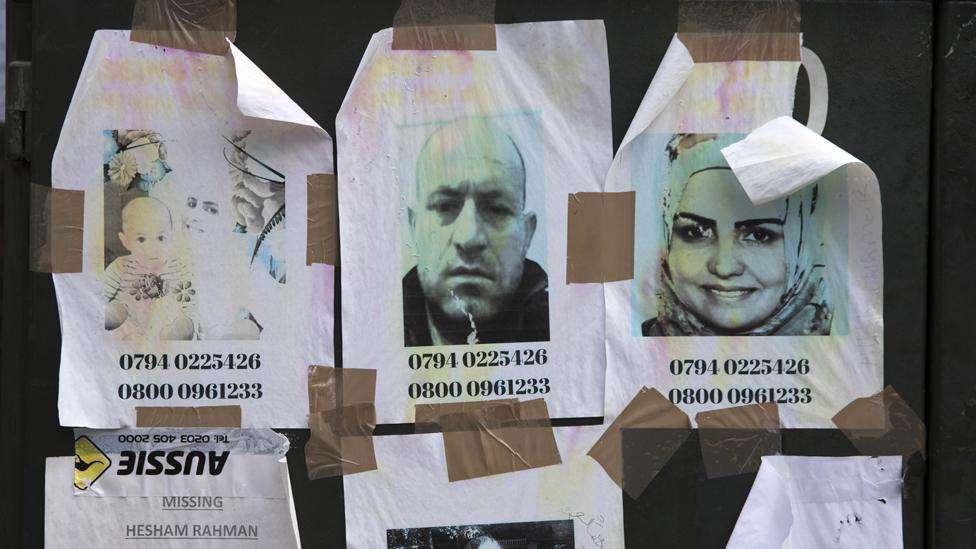

In its shadow, the faces of the missing are everywhere - on lamp-posts and bus shelters, railings and walls. Unblinking they stare, it is hard to hold their accusatory gaze.

A month after this appalling tragedy, we still don't know exactly who or how many people died at Grenfell Tower. Perhaps that tells us something about our fractured relationship with the people who lived there.

Some, perhaps, were happy to be anonymous. But others were simply marginalised and isolated.

Only the most vulnerable and desperate would have been eligible for a vacant council flat in the tower. Traditional social housing such as Grenfell has fallen out of fashion. Fewer such homes were built last year than at any time since their invention, with just 6,800 completed in England.

The first council blocks were designed for working people from all backgrounds. But over time, social housing has been "residualised" - increasingly available only to the most disadvantaged households - and that has consequences for a neighbourhood's relationship with wider society.

"For too long in our country, under governments of both colours, we simply haven't given enough attention to social housing," the prime minister told the House of Commons last month.

"In this tower just a few miles from the Houses of Parliament, and in the heart of our great city, people live a fundamentally different life, do not feel the state works for them and are therefore mistrustful of it."

In one of the gardens of the Lancaster West Estate, just a few yards from Grenfell Tower, I meet Pilgrim Tucker, a housing campaigner who has worked with the residents for a number of years and knew some of those who died.

"The fact that more and more it is only the most vulnerable people who can qualify for social housing means that there is a section of people here who become really disengaged," she says.

Local housing campaigner Pilgrim Tucker: "There is a section of people here who become really disengaged"

"There are people who live below the radar, homeless people who have been sofa-surfing, people living with family but not officially on the rent-book, refugees from war, people who have experienced some trauma in their personal lives or have mental health problems - those people, for one reason or another, don't have their voices heard."

The point is made that some residents had expressed their concern about the safety of Grenfell Tower but complain they had been rebuffed by officials. The borough-wide housing body supposed to protect residents, the Kensington and Chelsea Tenant Management Organisation (KCTMO), is far larger than such bodies are usually.

Most TMOs cover a single estate, ensuring local people's voice is heard loud and clear. The KCTMO manages almost 9,500 properties and one of the questions for the public inquiry will be whether it became too remote from the safety concerns of a few residents from a block of 120 flats in the north of the borough.

More from the BBC

"This is the story of some of those who were in the fire, told through friends and family who were in touch with them during those desperate hours, and in the words of those who survived."

We do know that about 250 people escaped Grenfell during the fire, but it is now apparent that 80 are missing or confirmed dead. They had arrived at the tower from all over the world - more than 20 countries were represented.

There were families with small children who had recently moved in and pensioners who'd lived in the block for over 40 years. And then there were the unknown.

In a sea of extraordinary affluence - Kensington is the wealthiest constituency in the country - the area around Grenfell Tower is an island of deprivation. The neighbourhood is among the poorest 10% in the UK.

It has been like that for centuries. In 1851, Charles Dickens wrote of the parish of Kensington as being "studded thickly with elegant villas and mansions", but also an area that included "a plague spot scarcely equalled for its insalubrity by any other in London".

Echoing the Dickensian observation, London Mayor Sadiq Khan tells me the fire had revealed London as a tale of two cities.

A vigil was held near Grenfell Tower to mark four weeks since the fire

"There are many Grenfell Towers where there are hidden Londoners who officials don't know about," he says. "Their experience of politicians of all parties, local politicians and national politicians, is them letting them down, is them making promises they don't keep, or them never being seen save at election time.

"So don't be surprised if they don't vote, don't be surprised if they don't take part in the normal democratic norms that you and I take for granted. They feel let down for years and years."

The mayor thinks Grenfell has exposed the failure of politicians to "walk in the shoes of some of those residents".

Theresa May agreed with that sentiment in her statement to MPs: "Let the legacy of this awful tragedy be that we resolve never to forget these people and instead to gear our policies and our thinking towards making their lives better and bringing them into the political process."

The sense of being isolated from power is very strong in the community around the tower. That helps explain the extraordinary response in the early hours of that Wednesday morning. I met a local woman who had just pulled clothes from her wardrobe and food from her cupboard to give to her neighbours in need. These are people who have come to rely on each other.

Donations of food and clothing were quick to arrive after the disaster

People don't trust the authorities to take care of them and keep them safe, or be there in their hour of need. The new leader of Kensington and Chelsea council, Elizabeth Campbell, has apologised for the local authority's response to the disaster. "This is our community, and we have failed it when people needed us the most," she said.

To help distil the vital community spirit in the area, a boxing club was set up at the foot of Grenfell Tower, now destroyed. Since the fire, there has been a public fundraiser that has meant the local boys are back in training in the corner of a nearby car park.

A boxing club - once housed in Grenfell Tower - now meets in a nearby car park

"We have friends that lived in there, and the kids are in a desperate state," boxing trainer Gary McGuiness says. "There are more tragedies coming out every day."

The club is about building the resilience of children from tough backgrounds - resilience desperately needed right now.

"It's harrowing really that we might never know some of those victims, nameless people," mother and club volunteer Colleen Spencer Gittens says. "You can still see missing posters around when you are walking around in shops, it's very, very sad and I wouldn't have expected something like that to happen in the 21st Century in London to be honest."

That is the point. For something like this to have happened in one of the richest boroughs in one of the richest cities in one of the richest countries in the world is not just unexpected. Grenfell Tower is black with urgent and unanswered questions.