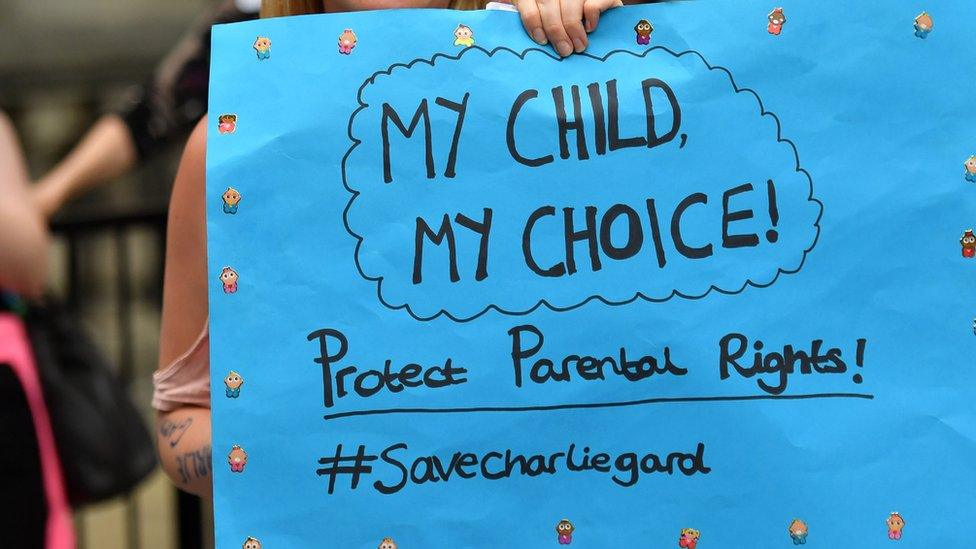

Reality Check: Why don't Charlie Gard's parents have the final say?

- Published

Parents, it is generally agreed, are allowed to choose what happens to their children.

Of course, parents may make good or bad choices, but they have the right to make those decisions, whether that is about their child's diet and physical activity, their name, what school they go to, what religion they are raised in or what medical treatment they receive.

Professor of medical ethics at the University of Oxford, Dominic Wilkinson, says: "The principle is that if parents' decisions risk significant harm to their child then they should not be allowed to make those decisions. But the state doesn't intervene every time parents don't make the best decision."

The concept of parental responsibility is set out in law. The Children Act 1989 describes it as "all the rights, duties, powers, responsibilities and authority which, by law, a parent of a child has in relation to the child and his property."

If a public body disagrees with those choices, they must go to court in order to override this parental responsibility.

In the case of terminally ill baby Charlie Gard, medical professionals disagree with his parents over what is in his best interests. They want to stop his parents taking him to the US for experimental medical treatment, something they say is futile. And they want to stop providing his life support and allow him to die.

His parents say they believe that Charlie is "not in pain and suffering" as doctors have claimed, and there is nothing to be lost in trying the experimental therapy.

The team at Great Ormond Street has said Charlie is suffering and that that outweighs the "tiny theoretical chance there may be of effective treatment".

Charlie is unable to move his legs and arms, breathe unaided or hold his eyelids open. He is also deaf, has severe epilepsy and his heart, liver and kidneys are affected.

Undoubtedly, both doctors and parents want the best for Charlie. But in the final analysis, it will be for a judge to decide. This is because in the UK, in the absence of a parent's consent, a hospital needs a court order if stopping treatment would bring about death.

So far, the courts have ruled that Charlie should not be given treatment and that Great Ormond Street Hospital should be allowed to withdraw Charlie's life support.

Chris Fairhurst, children's law expert from Slater and Gordon, explains that in these situations, parents' wishes can only be overridden by going to court because a hospital has no legal right or responsibility to make such a decision without either the parents' or the courts' permission. It takes a judge ruling in favour of the hospital in order for the legal status of the parent's responsibility to be overridden.

The hospital has given evidence that it does not believe keeping Charlie on life support is in his best interests.

Connie Yates and Chris Gard have fought a long legal battle to take their baby to the US for treatment

Limits of parental rights

When it comes to cases involving the medical treatment of children, views range from thinking that the doctor always knows best to the idea that parents should have complete freedom to make all decisions over their children's health. The law in the UK falls somewhere in-between.

In 2006, the parents of a disabled baby boy called Mahdi Bacheikh, external won their fight against the hospital's request to turn off the ventilator that kept him alive. The 19-month-old had spinal muscular atrophy, was almost totally paralysed and could not breathe unaided, but did not have any sign of brain damage. He died later, aged two.

In 2009, the parents of a baby known only as OT , externalwho, like Charlie suffered from a form of mitochondrial disease, lost their right to keep him on life support. The judge heard he had suffered brain damage and was in discomfort and pain. He died the next day.

In the US, though, where Charlie's parents are suggesting he could be treated, the law falls much more heavily on the side of the parents even if this goes against the recommendations of medical professionals.

Charlie is thought to be the 16th baby ever to be diagnosed with his condition

Parents refusing treatment

In the UK, while parents have the right to make decisions about their children's medical treatment, their wishes will be overruled if they refuse a reasonable life-saving treatment which has a very high chance of working.

The classic example of this is parents who are Jehovah's Witnesses and refuse blood transfusions due to their faith. There have been many cases where the courts have sided with the doctors against the wishes of the parents.

There is a difference, of course, between parents refusing recommended treatment and parents, as in Charlie's case, asking for treatment against advice.

It is far simpler to prove that a treatment that almost certainly will keep a child alive is in their best interests than it is to argue that keeping a child alive is not in their best interests.

When it comes to disputes between parents and the state, the vast majority involve a local authority going to court to remove a child from the care of their parents. In these cases, the authority must prove that a child is at risk of significant harm.

But because cases like Charlie's are relatively rare, unlike in care cases there is no statutory test for how judges should treat them. This means it varies case by case as to whether a judge decides what is in a child's best interests or uses the more onerous test of whether they are likely to come to significant harm.

- Published27 July 2017

- Published13 July 2017