'I was named after a World War One battle'

- Published

Ella Passchendaele is one of a handful of descendants with the battle still part of their name

Passchendaele, Somme, Arras, Cambrai, Verdun, Dardanelles, Ypres and Jutland.

There were not only the names of World War One battles, but also the names given to babies, usually in commemoration of a father or relation who fought and died there.

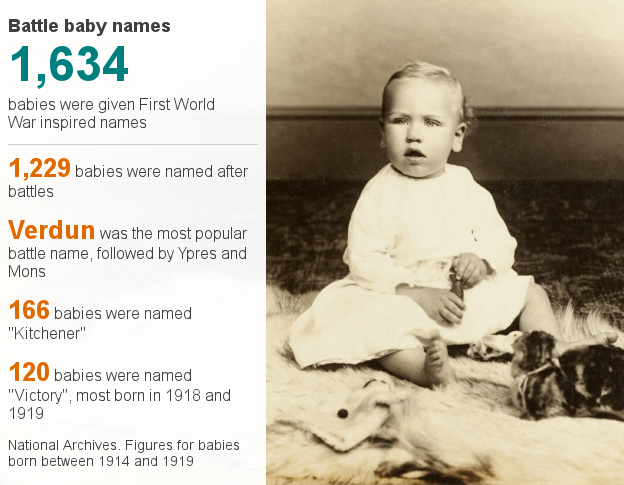

It might sound strange to modern ears, but more than 1,600 children during and after World War One were given names related to the war, even down to calling babies Vimy Ridge or Zeppelina.

The war literally became part of their identity - and they became a form of living commemoration.

The names tended to be given to girls rather than boys and the battle names were feminised, such as Sommeria, Arrasina, Verdunia, Monsalene and Dardanella.

With the centenary commemorations approaching for the Battle of Passchendaele, there have been efforts to trace families who have passed down these names through the generations.

Why were babies named after Passchendaele? Sean Coughlan reports for BBC Radio 4's PM programme

Ella Passchendaele Maton-Cole, a 19-year-old in Alton, Hampshire, is one of the few remaining people with a name taken from the battle of Passchendaele, which began on 31 July 1917.

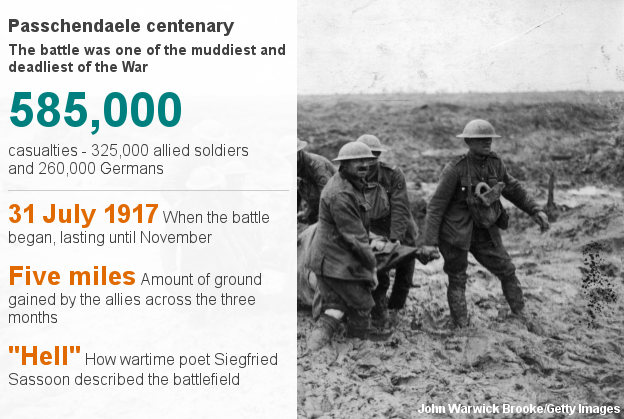

This became one of the most well-known battles of World War One, with appalling conditions, terrible casualties and great heroism. There were 320,000 killed and wounded on the Allied side, in a battle fought in mud so deep and treacherous that men drowned in it.

Ella Passchendaele's name was handed down through her great grandmother, Florence Mary Passchendaele, named after her cousin, Frederick Fullick, who had died during the battle in September 1917, aged 24.

Ella says the connection is "bittersweet", but she likes having a name with such history behind it.

She is a similar age to many of those who died in the battle in Belgium a 100 years ago and she says that the name gives her a sense of "connection".

Ella Passchendaele with her great grandmother Florence Mary Passchendaele

"It's not that I'm named after all the deaths," says Ella. But she is proud to be named in honour of an ancestor who fought there.

Researchers at the National Archives in Kew found a letter sent to Frederick's sister from an officer, who had been there when he died.

"I was in charge of the party of men who carried him to the dressing station and I can certainly assure you he was perfectly calm and collected," the officer had written.

Jessamy Carlson, a historian and archivist at the National Archives, says the naming of children after battles was a way of honouring the dead and for families to keep a "personal, tangible connection" with a lost husband, father or relative.

She says it also shows the "extent to which war became part of everyday life".

"You have an experience that is all pervasive. You have women whose husbands are away, dying far from home - and naming their children in this commemorative way is a way of holding them close," says Ms Carlson.

In the first stages of the war, the battle names tended to be generic locations - with children given names such as Belgium or Frances (after France) or Calais, where soldiers might have disembarked.

But Ms Carlson says that as the war progressed the names became specific to battles, such as Arras, Mons and Somme, and then down to particular parts of battles, such as Delville Wood.

The trend was particularly prevalent in south Wales - and the brother of the actor Richard Burton was called Verdun, after the battle in France. Verdun became the single-most used battle names, adopted by more than 900 families.

Passchendaele, with its huge casualties, also became a source of names for babies.

Passchendaele was one of the bloodiest and muddiest battles of the First World War

"The thing that Passchendaele is now most famous for is the mud. It started raining the day after the battle started and continued for a month and turned the western front into a quagmire," says Ms Carlson.

"The modern resonance of Passchendaele is the extensive loss of life and horrific conditions - and to see children named after this seems quite poignant," she says.

Chris Oswald from Wiltshire is from another family which used Passchendaele as a name, after a grandfather who fought there and won a Distinguished Conduct Medal for bravery.

"It's difficult now for modern people to understand the effects that it must have had on a generation, the cataclysm of World War One must have changed the way people saw things.

"I can understand that creating a memorial with a name like Passchendaele is something that would have seemed perfectly normal."

As the war ended, there was another flurry of names such as Peace, Poppy, Armistice and Victory.

There will be national commemorations for Passchendaele beginning next week, marking one of the most intense and controversial battles of World War One, which cost hundreds of thousands of casualties and saw the front line moving only by a few miles.

Culture Secretary Karen Bradley says it was "very touching" to think of those who died there being remembered through the descendants named after them.

"It is fitting, that in its centenary year, we are uncovering the forgotten stories that link people to Passchendaele," she said.

Ella Passchendaele is one of a handful of people who still have the name.

The monumental attack on German lines on a summer day in Belgium in 1917, is now in the name of a teenager talking on a summer's afternoon in Hampshire a century later.

She says when she was at school she was always being asked about a name that seemed so unusual.

"I used to write my name on my text books and everyone would say: 'What is that?'"

Now she says she wants to carry on the name for another generation. "That's why when I'm older I'll be naming my children Passchendaele for their middle names."

You can listen to Ella Passchendaele and the story of the "battle babies" on BBC Radio 4's PM programme.

- Published3 January 2017

- Published12 July 2017

- Published26 May 2017