How Britain supported the early release of Rudolf Hess

- Published

Files from the National Archives reveal that the British government supported the release of the Nazi war criminal Rudolf Hess as early as 1956.

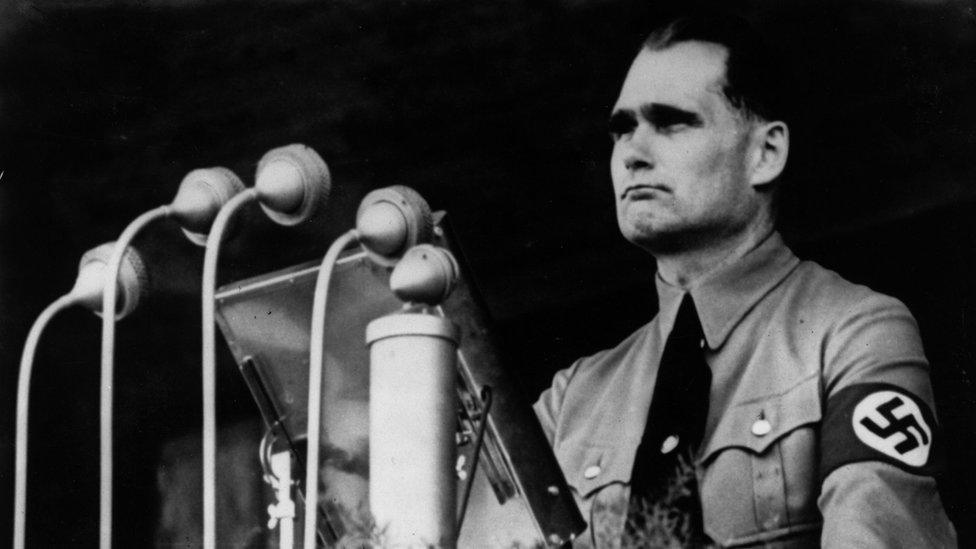

Rudolf Hess was Adolf Hitler's deputy and, for a while, one of the most powerful figures in Nazi Germany. He is mainly remembered for flying to Britain in 1941 in a bizarre and unsuccessful solo peace mission, which resulted in his arrest and imprisonment for the rest of World War Two.

After the war Hess was sentenced to life imprisonment and spent the rest of his days in Berlin's Spandau Prison. For much of his time he was its only inmate.

But Foreign Office files released on Thursday show that the British supported Hess's release more than three decades before his suicide in 1987.

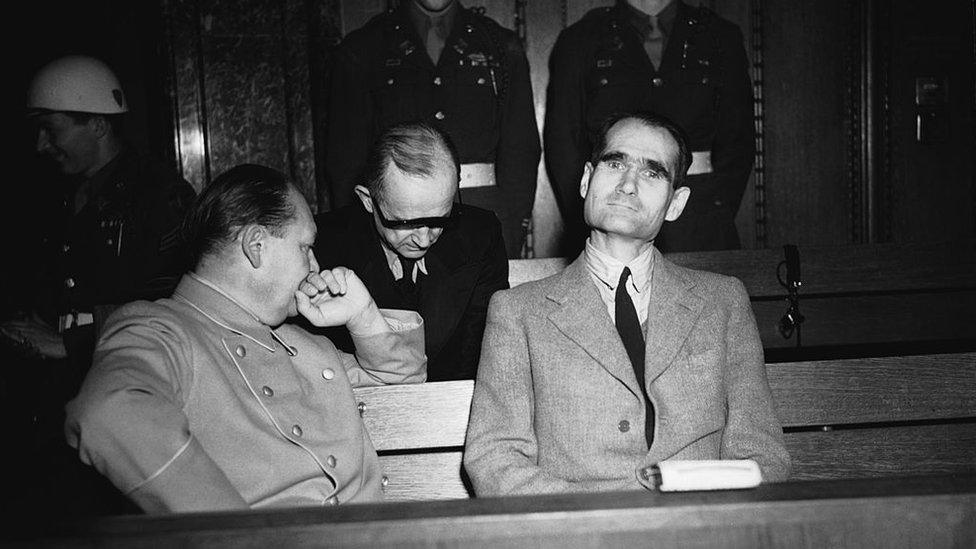

Hess was sentenced at the Nuremberg trials in 1946 by the so-called Four Powers - the UK, the US, France and Russia - and support for his release was needed by all of them before any change could be made. By 1966, the six other prisoners held in Spandau - including Hitler's architect, Albert Speer - had been freed or had died.

Hess, by this time 72, was to remain Spandau's solitary prisoner for the rest of his life. While healthy for his age, Hess was inevitably frail. His son organised a campaign for his release, receiving considerable press coverage in West Germany. There was also growing support for this in the UK.

Hess at the Nuremberg trials, sitting next to Hermann Goering

The files show the British government stepped up its efforts to have him freed. In 1979, just after becoming Foreign Secretary, Lord Carrington wrote a particularly strong note to his Soviet counterpart Andrei Gromyko. "It would be both inhumane and pointless," he said, "to insist that this old man should die in prison."

In all, the British made 11 unilateral appeals for Hess to be freed. The Americans and French supported them in a further nine. The Soviets always refused to consider the case.

Nearly 40 years after the end of the war, Soviet politicians and diplomats argued that the release of such a leading figure in the Nazi regime would not be understood by the Soviet people, or by others who had suffered. One diplomat said he was not convinced by the so-called humanitarian argument - "The suffering which he and other Nazis had inflicted was not human," he said.

Tony Le Tissier was the last British governor of Spandau, holding the post in the decade leading up to Hess's death. There were also French, American and Russian governors - they took turns to run the prison, for a month at a time.

Tony Le Tissier, the last British governor of Spandau prison

The rules of Spandau, drawn up after the Nuremberg trials, were harsh. Prisoners were only to be addressed by their number, never their name. Punishments were strict. When in 1955 Hess failed to greet a Soviet warder, he lost all his reading materials for 10 days.

Prisoners could be put on bread and water, or placed in punishment cells. But Le Tissier says that by the time he arrived, the regime was far more relaxed. Although Hess was supposed to be called Number Seven, not everyone stuck to that - some officers did address him by name. He was not supposed to watch the television news - but that wasn't rigidly enforced either.

He could go into the garden when he chose, and he had two cooks to prepare any meal he wanted. "He ate an awful lot!" says Le Tissier. "Quite a surprising amount."

Le Tissier did chat to Hess but he says the prisoner never talked about his past: "It was a closed circle - never came into it." Neither did they ever talk about the news or politics.

Spandau Prison

Constructed in 1876 on Berlin's Wilhelmstrasse in the western district of Spandau

Initially used as a military detention centre, the prison held civilian inmates from 1919 and was used by the Gestapo during Nazi rule

Apart from Hess, the prison held six other Nazi prisoners after WW2 - Konstantin von Neurath, Erich Raeder, Karl Donitz, Walther Funk, Albert Speer and Baldur von Schirach

After Hess's death, the building was immediately demolished to prevent it becoming a neo-Nazi shrine. A shopping centre was later built on the site

While Le Tissier tried to make Hess's stay as comfortable as possible, organising new chairs for his room for instance and a new bed, he did not personally agree with the argument that he should have been freed. Le Tissier thinks Hess deserved to die in prison, for all that he had done.

"He got his just deserts," he says. "He was a fanatical Nazi - an enemy. I did feel very strongly that he was there till he finished."

In August 1987 Hess killed himself, wrapping a lamp cord round his neck. Some suggested he was helped but Le Tissier is convinced that Hess acted unaided. Security was extremely tight in Spandau, he says. There was only one key to the gate, and only the chief warder had it.

Le Tissier recalls his reaction: "It was a fait accompli - it was over." He thinks it was a good thing. "It was such a waste of time and money, involving so many people."