From Baghdad to the bar: A blind refugee's journey

- Published

As Aphra watched her son Allan graduate from Cambridge University last month, she thought back to the moment he was born.

"I'm so sorry your baby is blind," a neighbour in Baghdad had said.

Aphra became the talk of the town because of the taboo associated with her son's condition.

It was Iraq in 1995 - Saddam Hussein was president, the Gulf War had ended only three years earlier and citizens were suffering under sanctions placed on the country.

As a blind child, Allan Hennessy's prospects were poor.

Political unrest in Baghdad, Iraq in 1992

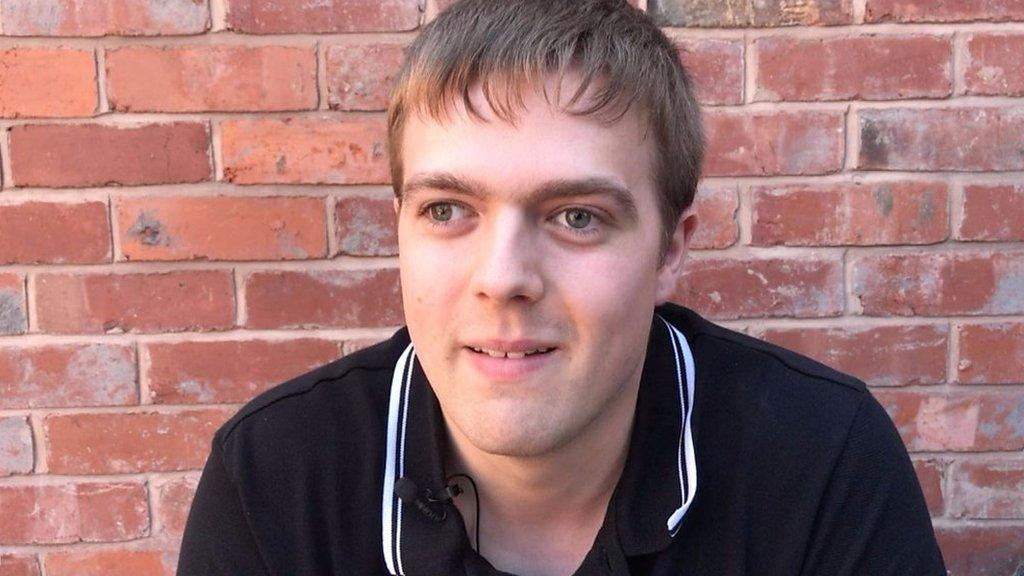

Today, walking around his college in Cambridge, Allan is confident and articulate:

"I have so many accents now," he says.

"If someone from Iraq calls, I answer in Arabic, 'As-salaam-alaikum'.

"At Cambridge I have a posh, round-vowelled voice.

"Then I speak to a mate from the estate - 'Oh my days, all right bruv?'

Allan Hennessy was born totally blind in Iraq after the Gulf War.

He is only 22 but already Allan has smashed barriers that many will not face in a lifetime.

So how did a baby born blind in a war-torn country become a top student at a world-leading university?

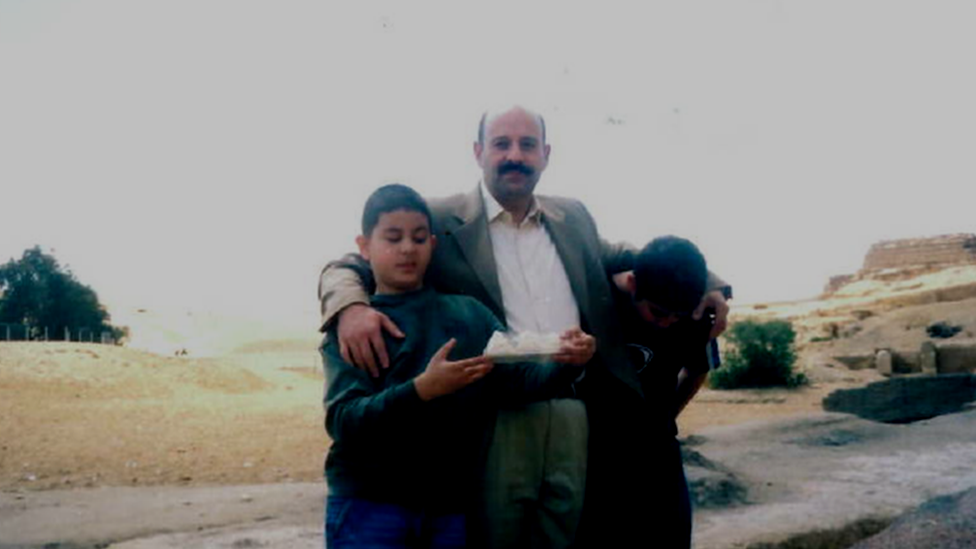

In Iraq, Allan's family were middle class - his grandfather was a sheikh and they lived a comfortable, even luxurious life.

But Iraqi hospitals could not offer Allan hope of sight.

"My dad tried to get me treatment but there weren't enough eye specialists - they thought I would always be blind."

But when Allan was six months old, an opportunity came and Allan's father seized it.

"My dad sold up to pay for the treatment - his car, belongings, some of his land. We left Iraq with very little."

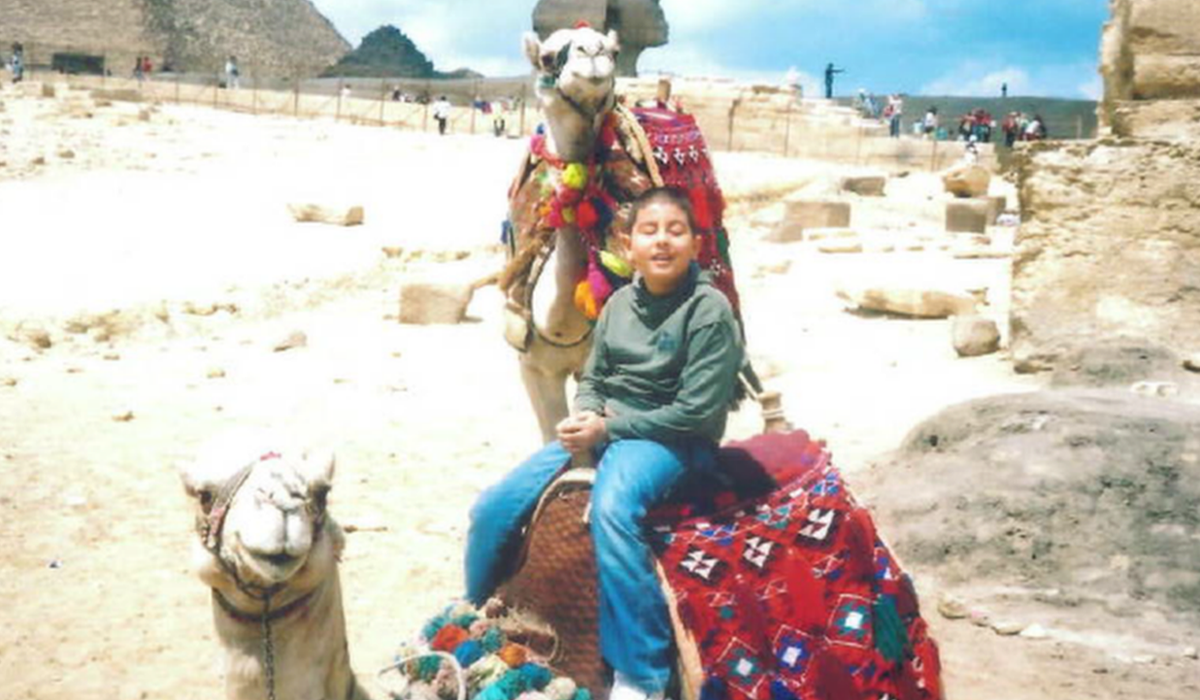

An eye operation in London restored partial sight in one of Allan's eyes

The opportunity was an operation in London which restored partial sight in Allan's left eye.

"My mum remembers the first time I looked at her - the first time we made eye contact. She burst into tears.

"Since then I've just been rocking on with the little sight I have," he explains.

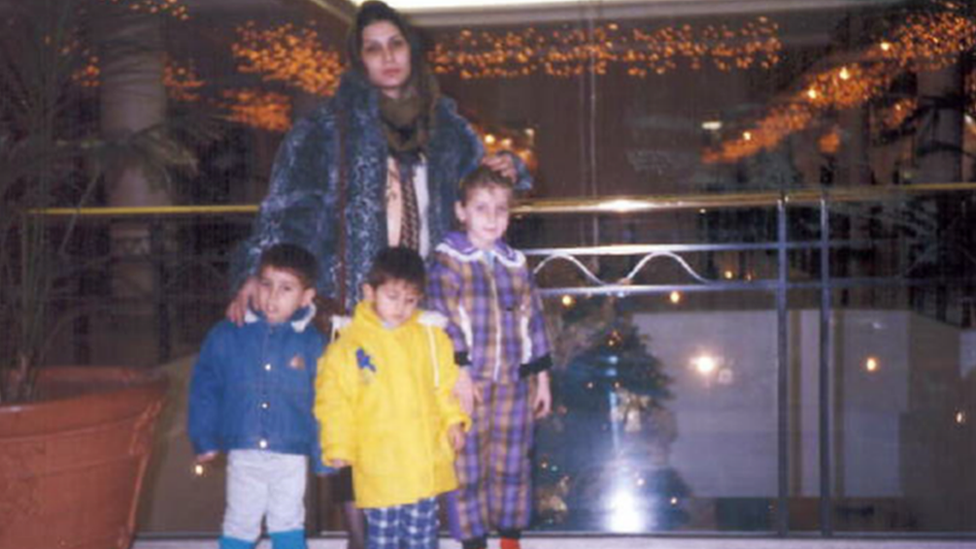

Allan with his family

Allan's mother and his siblings also sought political asylum in London, but life as immigrants was challenging.

"They enjoyed their life in Iraq, but when circumstances changed, they were forced to become refugees.

"They did not speak English, and we lived on London council estates - they had a real culture shock."

Allan and his siblings meeting Father Christmas

"Jihadi John" - who joined so-called Islamic State in Syria and appeared in videos showing beheadings of prisoners - grew up on the same estate.

Although Allan is visibly uncomfortable at any mention of the militant, the link highlights the difference between his childhood and many of his peers at Cambridge.

"When people at university ask me about my life, they think 'he's had a really difficult life'.

"But the reason I'm able to get on with it is because I look back at my family in Iraq and I think I'm very privileged."

Allan is not the type of person to do what he is told.

"I've lived my life thinking I'm not partially-sighted.

"I loved riding my bike and climbing scaffolding, even though I wasn't really meant to.

"When we went to the fairground, I always wanted to drive the bumper cars."

Like many children, Allan was no angel at school.

"I was in the lowest set for everything and I would bunk off school. I threw eggs at buses, stuff that teenagers do," he says.

But eventually Allan realised he could do better:

"After GCSEs I got a new energy and I realised the kids in the top sets weren't any smarter than me."

In 2012 he applied to study law at Cambridge University.

"Everyone and everything was so white - I felt visibly different," he says, recalling his first impressions.

He became one of only seven people with impaired sight accepted, external that year and the first person in his family to attend university.

"All my life I've been told I cannot, must not, should not and would not. The disabled stereotype is subdued, helpless - and the biggest struggle for me is to overcome that stigma.

"When you leave your lane, you are treated with negativity and scorn. You receive a lot of hatred for what you do, but all you're doing is what 'normal' people are doing," he says.

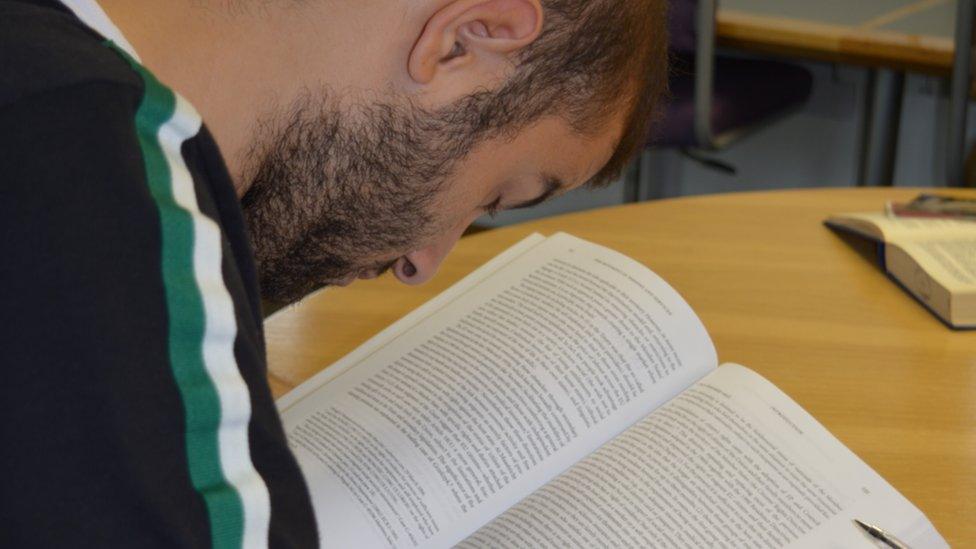

Allan spent three years at Fitzwilliam College and says it has been transformative.

"I met the most amazing people from all over the world. But there was also a lot of negativity directed at me.

"When you're an overweight, brown, blind guy climbing the greasy pole, everyone can see and they judge you - even though they are doing it too."

What would his life be like if he had stayed in Iraq?

"I wouldn't have a Cambridge law degree - I wouldn't even be sighted.

"My family there have faced terrible, traumatic events, including capture by so-called Islamic State.

"Perhaps I wouldn't be alive."

Allan with his mum at graduation

After graduating this summer, Allan is taking up a prestigious scholarship at law school.

"If you've got a first-class law degree from Cambridge University, that should set you up for life," he says.

"But when you're a blind, Muslim immigrant living in Britain today, there is so much more I have to do. The journey has only just begun."

By UGC & Social news

- Published22 July 2017

- Published14 July 2017

- Published10 July 2017

- Published26 March 2016