USS Indianapolis's discovery 'offers closure' to survivors

- Published

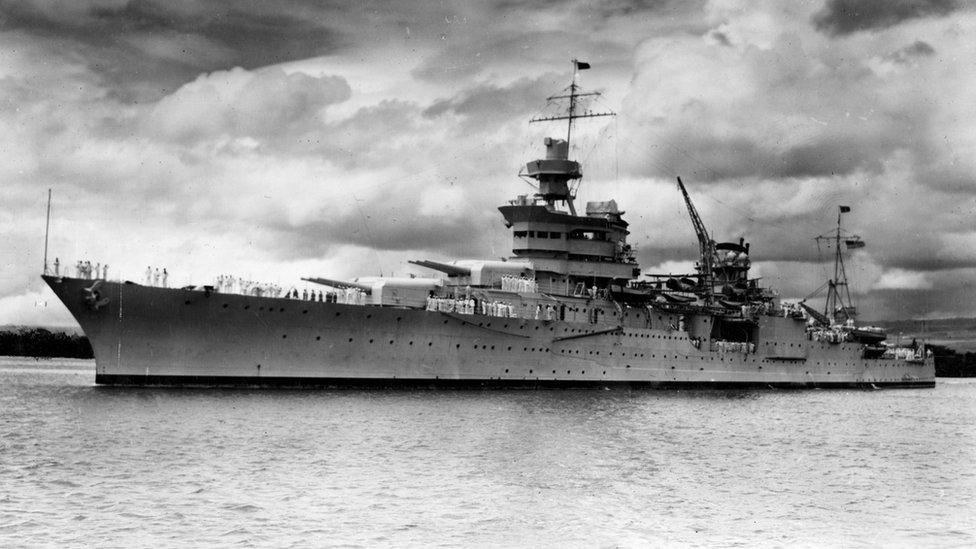

The last time the crew of the USS Indianapolis saw her, she was sinking beneath the Philippine sea, torn apart by torpedoes. So how do her surviving crew and the families of those who died feel now the ship has been found?

Until the ocean finally gave her up earlier this month, the whereabouts of the USS Indianapolis were a mystery for 72 years.

Sunk in a remote area on 30 July 1945, somewhere between Guam and Leyte, she was incredibly hard for the civilian search team, led by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, to find.

That's part of the reason why surviving crew members spent four days and five nights in shark-infested waters, before a near-miraculous rescue came.

But it came too late for many. Of the 1,196 men on board, some 800-900 entered the water. Only 316 were pulled out of it - still the largest loss of life at sea in the history of the US Navy.

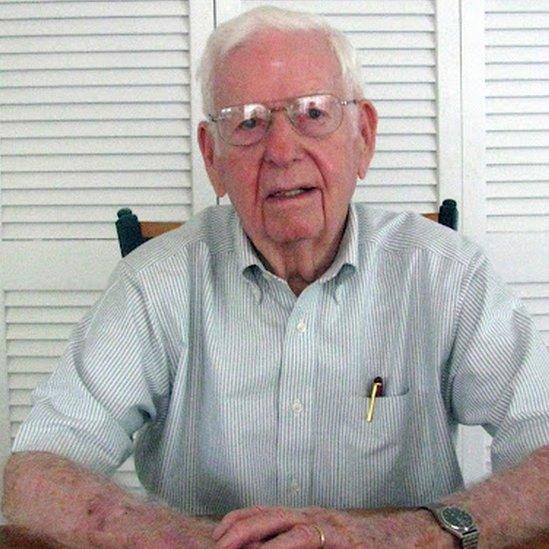

One of those who endured those horrors is John Woolston, who was a 20-year-old ensign. He's now 93 and lives in Honolulu, Hawaii.

He's seen the eerie images of the Indianapolis now, which show an anchor, one of the ship's bells, and her hull all peering through the gloomy waters, 18,000ft (5.5km) down.

"I had two emotions on seeing the ship again," John says. "Joy that it has been found, and disappointment at the condition it's in, at the bottom of the ocean with all that damage.

"It's very painful to think about what happened. But I am very glad they found it."

A civilian search team, led by Microsoft co-founder Paul Allen, found the USS Indianapolis

John proudly mentions his qualifications several times. He was a naval architect and studied at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. He explains that this means he has a "technical interest in the wreck, as well as the emotional interest".

He understands how ships are built and is still keen, after 72 years, to learn exactly how the Indianapolis was damaged when two Japanese torpedoes slammed into her.

She sank in 12 minutes, and it has long been reported that a distress signal was not sent in time. However, there are recent claims, external that signals were actually transmitted, but ignored.

John describes how at exactly midnight he was relieved of his position and went to get a coffee and a sandwich in the wardroom.

Suddenly there was a "large boom from the front, and another from underneath," and he was thrown to the floor.

John made his way to the deck and found the ship listing at a 30 degree angle. Eventually she rolled over, forcing John and his crewmates to slide off her hull into the water.

"The last time I saw her, the stern rose up with one of her propellers still slowly turning. Then she went down, out of sight."

After his rescue, John Woolston recovered on the Western Pacific island of Peleliu

John describes the first few moments of being in the sea as chaotic, with no time to think. Eventually he managed to get hold of a lifejacket.

"I tried to stay afloat, and help those who got into trouble. Some people went crazy. It's a universal thing where you don't want to die alone, and they wanted other people to join them."

Although exhaustion, heatstroke and dehydration killed many of those in the sea, a good number were also taken by regular shark attacks. These horrors have been recorded by several surviving crew members, but John declines to go over that part of his life again.

"I don't talk about that with people," he says politely, but firmly.

When the rescue came, it was by accident. A US plane on a routine antisubmarine patrol spotted the men and raised the alarm. When rescue ships arrived, John says his condition was "pretty close to terminal".

"I don't think I could have lasted more than another four hours."

When he arrived in Guam, John found that he was the only damage control officer from the ship left alive, so he was the one who wrote the ship's damage report.

John Woolston is now 93 and lives in Hawaii

The Indianapolis was sunk while returning from its secret mission to deliver parts for the atomic bomb which was later used on Hiroshima.

Among its crewmates was Jack E Walker, a 23-year-old radio operator. He had only been married for less than three months to Ruby Taylor when he set sail.

The childhood sweethearts had been together for five years, and when Germany surrendered on 7 May, they thought the war was over, so got married.

But Jack died when his ship was sunk, and while the couple suspected Ruby might be pregnant, they weren't sure when he left.

"The last letter he wrote to me asked me to write as soon as I'd heard back from the doctor," says Ruby. "He was anxious to know if I was pregnant, and whether it was a boy or girl."

But Ruby's letter confirming that she was carrying the couple's child was returned, as it did not reach Jack in time.

Ruby Taylor now has nine grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren

Ruby, now 93 and living in Indiana in the US, says seeing the wreck of the USS Indianapolis gave her a sense of closure.

"I felt relieved when the search team said they know where it is. I spoke to my family and we all felt better knowing that. In a way it's great, in a way it's bad.

"I think Jack might have been on duty and went down with the ship. I hope he did. The men in the water suffered, so I hope that's where he is."

Ruby still has all of Jack's love letters to her. Their daughter, Cathy, died five years ago. Later, Ruby married a man who was already a friend to her and Jack, and they had three daughters. She now has nine grandchildren and eight great-grandchildren.

"They all got on well and it all worked out fine in the end." Ruby pauses. "But there's nothing like the first love."

Harlan Twible gave the order to abandon ship in his section of the USS Indianapolis

Harlan Twible, 95, who lives in Sarasota, Florida, was a 23-year-old ensign on the ship. He hopes it's now left where it is.

"I've talked to some of my shipmates's relatives and they're pretty happy the Indianapolis has been found."

Harlan was on watch when the torpedoes struck. "I gave the order to abandon ship in my part of the ship. I didn't jump into the sea - the ship tipped me in.

"When I was in the water I watched the ship go down. It was a sad sight.

"We all swam away as she went. We tried to save as many men as we could when we were in the sea. We didn't save as many as we'd have liked."

Harlan says he had "mixed emotions" about the search for the USS Indianapolis.

"I would hope it offers some closure to the widows and survivors. But it's pretty difficult to look at a ship with your shipmates in it at the bottom of the sea."

- Published21 August 2017

- Published29 July 2013