Slaves in modern Britain: 'Living in the dark'

- Published

Maria and Kim say they were paid nothing for their work

One woman clutches a tissue. Then, a simple question: "What happened to you?"

That's when the tears come. "My employer is not good for me…"

Maria has barely got her first words out when the emotion overwhelms her.

She continues her tale, weeping, sniffing. You can barely make out what she is saying. But you do not need words to understand.

She was born in the Philippines and left the country to take up a job as a domestic worker for a woman in the Gulf.

Raw fear

In April this year, she moved to Britain. Maria got a visa and came in legally. Since arriving, she has been exploited - sometimes, barely fed. She is expected to work round the clock. She has not been paid for five months.

Maria escaped from her employer just the week before she gave this interview. Her fear is raw.

Kim escaped a similar situation some time ago. Yet even for her, the memory of the way she was treated by the people who employed her as a maid is still painful.

There are tens of thousands in slave-like conditions in the UK, says the anti-slavery commissioner

"This family, they think you are rubbish. One time they tell me, 'All you Filipina are slaves.'"

Like Maria, Kim is not her real name - we are protecting both women as they have recently managed to escape.

They are being helped by a charity - Justice for Domestic Workers.

The people Kim worked for flew here in a private jet to live in a mansion. She has not been paid a penny.

Toy clue

It is estimated there are 40 million people living and working in slave-like conditions globally.

Even in the UK - which the country's anti-slavery commissioner, Kevin Hyland, says is "streets ahead" of other countries - it is thought there are tens of thousands.

The British government has made tackling slavery a priority.

At Britain's borders there are more officers trained to spot people-trafficking.

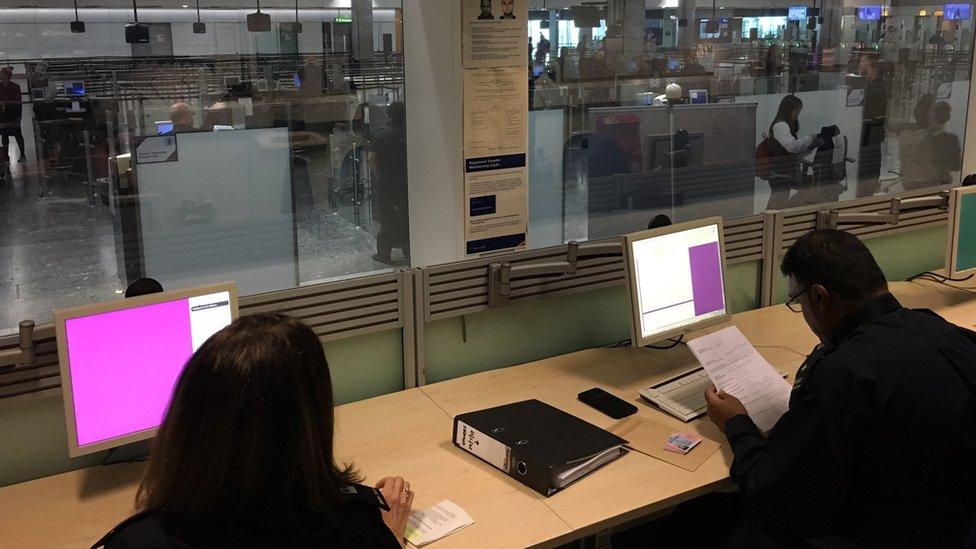

From the control centre behind the one-way glass at Heathrow airport, they are keeping a close eye on who is coming in, their documents, any signs of distress.

Officials watch at Heathrow airport for signs of potential trafficked people

But how do you spot modern-day slaves - when often even they will not know the kind of treatment they are about to receive once they arrive? Training helps - so does a bit of luck.

Amanda Reid, the national operational lead for safeguarding and modern slavery in the Border Force, remembers one such moment.

"The roving officer at the gates spotted a young lady carrying a really rather large Disney toy and happened to say, 'What's that for?' and she didn't have an immediate answer.

"Very soon after that we then saw another [young lady carrying a really rather large Disney toy].

"And this was really an indication something wasn't right.

"Her story unravelled, and it was clear she was heading for exploitation."

Immigration officials say the toy was being used by criminal gangs as a "marker". The toys were meant to identify the victims of trafficking to the people meeting them in arrival halls

Duped or coerced

In the first three months of this year, more then 200 potential victims have been identified at the British border.

But the efforts go far beyond one national boundary.

This is a $150bn (£110bn) a year industry. And in source countries around the world Britain has officers working with local officials to help victims, and to educate people about the dangers of falling into the traffickers' trap.

That is the kind of international approach Justine Currell wants to see happen more.

She helped draft the Modern Slavery Act at the Home Office. Now, she is the executive director of Unseen - a charity helping victims of slavery.

People "either come here for a better life", she says, or they are "duped or coerced or deceived into thinking that there is a job for them in the UK".

"Many of these people are then in debt bondage," she says.

"Their travel has been paid for, the work that they thought they were going into has been paid for, they then need to pay their exploiter back."

Problems getting help

Victims can get help through the National Referral Mechanism, the government-funded support service.

But many of the foreign-born victims, who do not have the right paperwork to stay here, do not trust the system and fear it exists to send them back to their country of origin.

Victims struggle to be believed, says anti-slavery commissioner Kevin Hyland

The anti-slavery commissioner says this part of the system needs reform.

Mr Hyland says it focuses too much on the immigration status of the victims, rather than the crime itself.

"There is no other crime where someone has to jump through hoops to be believed," he says.

The Home Office says a review of the National Referral Mechanism (NRM) has taken place.

It expects to announce some changes later this year.

That may come too late for Kim, Maria, and another woman also recently freed from slavery in the UK.

'Living scared'

Patricia made the decision some time ago not to apply to the NRM, and has now joined the ranks of the perhaps one million people in the UK living here without permission.

"It's like living in the dark," she says.

"I'm living scared every time I'm in the train, in the bus. I'm thinking I will be caught and sent to the Philippines."

Why stay, then?

"It's financial - I can support my family, my daughter and also my siblings, some of my nephews and nieces so they can go to school."

She adds, trembling: "Even if my situation is like this, I stay here because I can help them."

So she remains vulnerable, and in the shadows.

You can download a podcast of Matthew Price's reports, on the BBC Radio 4 Today programme website.

- Published10 August 2017

- Published4 April 2017

- Published11 September 2017

- Published11 August 2017