Why Cage director was guilty of withholding password

- Published

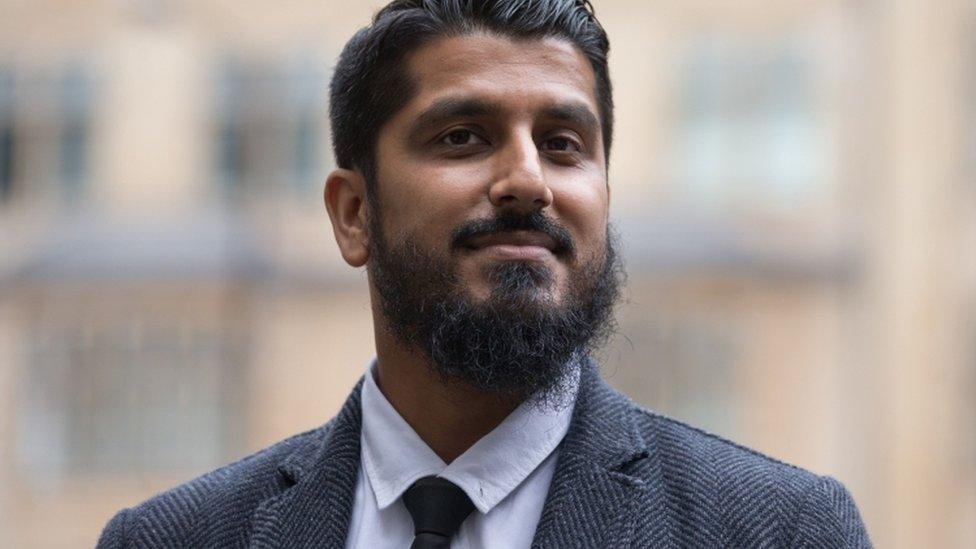

Muhammad Rabbani: Convicted - but set to appeal

One of the directors of the controversial campaign group Cage has been found guilty of wilfully obstructing police by refusing to hand over his phone Pin number and laptop password after being stopped at Heathrow Airport last year.

Muhammad Rabbani, 36, told a one-day trial that he had refused to let counter-terrorism officers look at information on his devices because he was carrying sensitive information from an alleged victim of torture by US agencies.

The officers who stopped Rabbani last November asked to see what was on his phone and laptop under a wide-ranging power used at ports to identify people involved in terrorism.

But Rabbani said that handing over the Pin code and password were like handing over the keys to his house.

He and his legal advisers have already said that they will appeal against the conviction because they not only believe he has been wrongly convicted, but because, in their view, the stop and search law behind the case is flawed.

Why is the law controversial ?

Schedule 7 of the Terrorism Act 2000, external permits police to stop and question anyone travelling through a port to determine whether they were involved in the "commission, preparation or instigation of acts of terrorism".

In the year to June, police stopped 17,501 people under the power. About 1,500 of those stops led to temporary detention for further searches and questioning - something that happened to Muhammad Rabbani.

He had been subject to seven previous Schedule 7s - and estimates that he's been stopped in other ways at least 20 times.

During two previous incidents, he had refused to hand over a phone Pin and he had eventually been allowed to go on his way.

This time was different. When PC Tariq Chaudhry asked Rabbani for access to the devices he refused, citing privacy and civil rights.

"I asked him questions about his occupation and he said he was a director of a company but wouldn't go any further," the officer told the court.

Muhammad Rabbani: "I have on the moral argument"

"He kept saying 'You don't need to and it won't help you in any way'."

The officer referred to colleagues and ultimately the campaigner was arrested and taken to the airport police station. Six months later he was charged with obstructing the police.

During that final interview, he gave police a prepared statement that said: "I considered that although the police were in law entitled to ask questions so that they could satisfy themselves I was not engaged in terrorist activity, that did not justify in addition being required to expose all the sensitive contents of my phone to being copied and undoubtedly disseminated not just to police but to intelligence services and possibly elsewhere in the world - an unjustifiable, uncontrolled acquisition of material."

Can the police seize anything anytime?

The police cannot automatically take devices off journalists or lawyers because there are special protections for the information that both may be carrying.

In the case of lawyers, they may be carrying legally privileged material relevant to a client's case. Journalists may have a notebook or laptop stacked full of confidential tips that are protected under the European Convention of Human Rights. If police want to see them, they have to get a court order - a judge balances the right of confidentiality with the police's need to see the material.

Muhammad Rabbani is neither a lawyer or a journalist - but he says he was carrying legal material that was highly sensitive and confidential.

He told his trial he had been in Doha, the capital of Qatar, to receive instructions from a client who alleges he was subject to torture over more than a decade at the hands of an US agency.

That material was on the laptop that came through Heathrow and would be used to start a legal challenge in both the UK and United States.

"There were around 30,000 [documents] which I was especially uncomfortable handling and I felt an enormous responsibility to try and discharge the trust that was given to me," he said.

Moazzam Begg: Turned out at court to support fellow campaigner

On that basis, he argued he had a right to privacy comparable to lawyers and journalists. If no right exists, then the demand to hand over Pin numbers and passwords amounts to an unjustifiable "digital strip-search".

Senior District Judge Emma Arbuthnot rejected the defence, saying he had taken a "calculated risk" to refuse yet again to hand over the Pin and password, despite being warned.

She handed him a conditional discharge - meaning that nothing more will happen if he commits no crime for the next 12 months - and ordered him to pay £600 in costs and a £20 victim surcharge.

However, Muhammad Rabbani' backers say that he is in fact the victim. As he left court, the large number who had come out to support him cheered, clapped and handed him flowers and a box of chocolates.

"If privacy and confidentiality are crimes, then the law stands condemned," he told them. This story has a long way to run.

Commander Dean Haydon, head of counter-terrorism command at Scotland Yard, said the verdict was important.

"Schedule 7 is a vital tool in the fight against terrorism," he said.

"We are committed to ensuring the power is used appropriately and proportionately, as it was in this case."

He said the Met had retained Mr Rabbani's phone and laptop and was "continuing its efforts to examine the contents".