Ex-prisoners lack support, says probation head

- Published

- comments

Too many prisoners leaving jail are merely being "signposted" towards rehabilitation services, the head of the Probation Service has admitted.

Michael Spurr said a new system of offender supervision in England and Wales "wasn't working" as it should.

Low and medium risk offenders are monitored by staff from 21 community rehabilitation companies (CRCs).

Managers involved say the system doesn't provide firms with enough incentives to tackle re-offending.

Mr Spurr addressed the issue at the annual conference of the Prison Governors Association near Derby, where one governor told him that 200 prisoners had been freed from the jail he runs with "next to nil" resettlement provision.

Mr Spurr responded: "CRCs are not working as we would have wanted them to work," adding that for many there was only a "basic resettlement service" available for offenders.

"Basic signposting is what's going on in a lot of places," he admitted.

Michael Spurr: "CRCs are not working as we would have wanted them to work"

The system was introduced by Chris Grayling, when he was justice secretary, to reduce re-offending rates among the 270,000 people who are released from prison each year or serving community sentences. For the first time, inmates let out after serving terms of less than 12 months were also subject to monitoring.

A new state body, the National Probation Service (NPS), was set up to supervise offenders assessed as posing a high risk of harm, with CRCs responsible for the rest, from 2015.

Although the NPS is considered to be performing satisfactorily, there are huge difficulties at the CRCs.

In a highly critical speech last month, Dame Glenys Stacey, the Chief Inspector of Probation, said: "Although there are exceptions, the community rehabilitation companies... are not generally producing good quality work, not at all."

Dame Glenys said new ways of managing offenders had "largely stalled", there'd been little "meaningful" improvement in helping prisoners resettle on release and less involvement by charities and voluntary groups than expected.

"We often find nowhere near enough purposeful activity or targeted intervention or even plain, personal contact," she concluded.

Dame Glenys Stacey has said that new methods of managing offenders have "largely stalled"

There appear to be three underlying causes.

First, the speed of the reforms. Mr Grayling wanted the plans to be embedded by the time of the 2015 general election to make it near-impossible for Labour to scrap them, should they be elected. That meant replacing 35 probation trusts with a part-privatised system within two years - without any pilot scheme.

Jacob Tas, chief executive of Nacro, a crime reduction charity which has a "strategic partnership" with the private firm Sodexo in six CRC areas, said that was a mistake, given the upheaval that had resulted.

"If you engage with this size of change, from my experience it's a good idea to test it out first and see and then learn and then make it better."

The new supervision system was introduced by Chris Grayling, when he was justice secretary

The second reason concerns the CRCs' contracts. They're required to hit 24 performance targets relating, for example, to the timely completion of reports, but only 10% of their predicted payments depend on cutting re-offending.

"We're hitting our target but maybe missing the point," said Chris Wright, chief executive of Catch 22, a charity which is sub-contracted by three CRCs to work with offenders.

He said ministers had put an "industry of bureaucracy" in place to keep companies under control.

"In a classic government way, they think the best way of holding people to account is by building a bureaucracy which ultimately takes you away from doing the things that really matter," said Mr Wright.

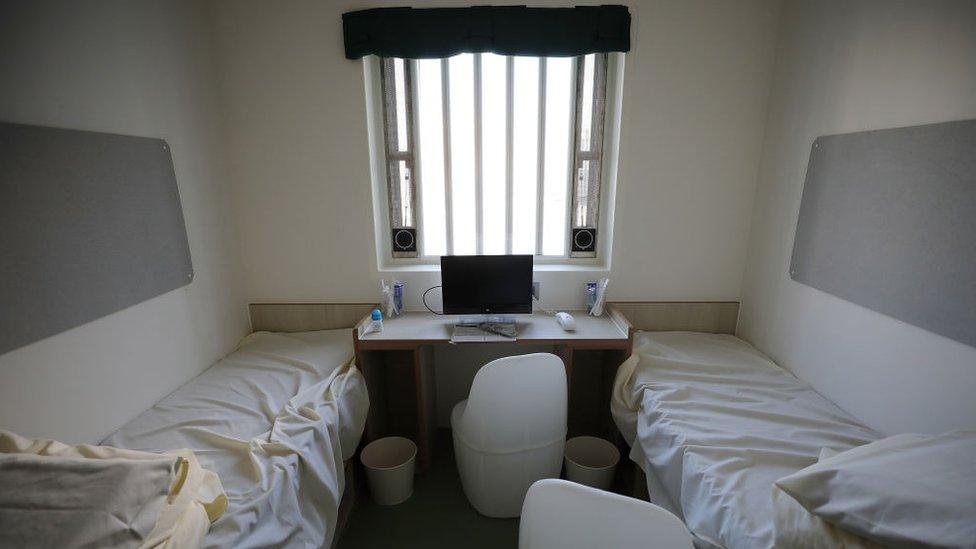

About 270,000 people are released from prison each year or are serving community sentences

It was a concern Mike Trace had when the charity he's in charge of, the Forward Trust, was bidding for CRC contracts.

"What became clear through the process is the innovation and the creativity to reduce re-offending was less important than the legal and financial risks or benefits," said Mr Trace. His organisation, then known as the Rehabilitation for Addicted Prisoners Trust (Rapt), withdrew from competing for contracts.

"I've got to say we were quite relieved not to be awarded any because they look to me to be misdirected and wrongly shaped," he said.

Thirdly, the way the payment mechanism for the CRCs was designed has left them with higher costs and lower income than they expected, leaving resources thinly stretched.

As a result, the government has adjusted the contracts, paying the CRCs extra money, which the Ministry of Justice said would amount to an additional £277m over seven years. Over a decade, the maximum potential value of the contracts is put at £6.5bn.

Michael Spurr said taxpayers would still end up paying less for probation than they did before the Grayling reforms, but after his acknowledgment of how "basic" the service is in many areas, some may question whether it's providing value for their money.

- Published23 September 2016

- Published16 February 2017