'How I got my children back'

- Published

John was devastated when his son Archie was taken into care

When John's son was placed into care at birth he was distraught - his drug abuse had been the cause. But with the help of a family court focused on reuniting children with their parents, his life began to change.

"Not only was I using heroin, I was using crack, I was using prescription drugs, I was using alcohol - and I was homeless."

John, who is 49, is candid when it comes to talking about his past addictions.

He started experimenting around the age of 14, and continued the habit during the birth of his two children - both with women who were also addicts.

It meant he didn't see his first child Daniella for long periods of time - at one stage as much as two years.

He says he and the mother "really tried to do normal life, but it didn't really work.

"It was a combination of the drugs and the lifestyle that went with that. Trying to be a parent, hold down a job - it wasn't doable," he explains.

Archie was taken into foster care from birth

When Daniella was 10, John found himself preparing for the birth of another child - his son, Archie, with another addict who had already had several children put into care.

He began looking for a place to live - having been homeless at the time - but failed to tackle the underlying drug problem.

After Archie was born, he was monitored in hospital to see if he had grown dependent on the heroin substitute his mother had taken during pregnancy. Then, he was immediately placed into foster care.

As John recalls this devastating period, he asks for a moment to compose himself, leaving his chair as he wipes away the tears.

Once he's ready to continue, he says it was seeing his son enter the care system that made him realise how out of hand his own life had become.

"That's when I knew this is serious, really serious."

Judge Crichton founded FDAC in 2008

John was assigned to a type of family court specifically designed to help parents keep their children, known as the Family Drug and Alcohol Court (FDAC).

Its aim is to place parents at the centre of the process - speaking to them directly rather than through lawyers, and having regular two-week sessions with the same judge.

Social workers and psychiatrists, as well as experts in substance misuse, domestic violence, finance and housing, are also available.

Watch Catrin Nye's full film about the Family Drug and Alcohol Court on the Victoria Derbyshire website.

It was founded in 2008 by Judge Nicholas Crichton after years of seeing families being broken up by court rulings.

"I often think it must be terrifying for a parent to have to come to [a traditional] court knowing at the end of the proceedings they may well lose their children," he says.

FDAC's task can, however, be substantial.

"I have seen mothers who have been heroin addicted from the age of 10, children who sleep on urine-sodden beds, where no-one has bothered to bath them or feed them properly," Judge Crichton explains, running through some of the cases he has seen.

Dr Mike Shaw says the effect FDAC can have by reuniting families justifies the cost of the service

For John, this approach made "total sense" - helping him to tackle "the problem that was right at the front".

FDAC helped him to arrange detox classes to combat his addiction, followed by a day programme.

The court is now receiving a further £6.2m of government money over seven years, through a complex financing structure - something called a "social impact bond" or "pay-for-success financing".

Private investors will pay the upfront costs and if the process works they make a profit - being paid back by the local authority and the government.

If it fails, they will not receive that money.

Dr Mike Shaw, a child psychiatrist and co-director of FDAC National Unit, concedes that it makes the process more complex, but says it will ensure the service strives for the best outcome.

But its work does come at an inflated price.

Each intervention costs around £13,000 a year, he suggests, compared to £5,000 for standard care proceedings.

He says, however, that the overall cost of care proceedings might in some cases be as much as £100,000.

Minister for Sport and Civil Society, Tracey Crouch, says the additional FDAC funding will "benefit some of the most vulnerable people in society" and "achieve real results in communities across the country".

At one stage, John went as long as two years without seeing his daughter Daniella

John's intervention lasted around 16 months - at which point he estimates he had been clean for a year.

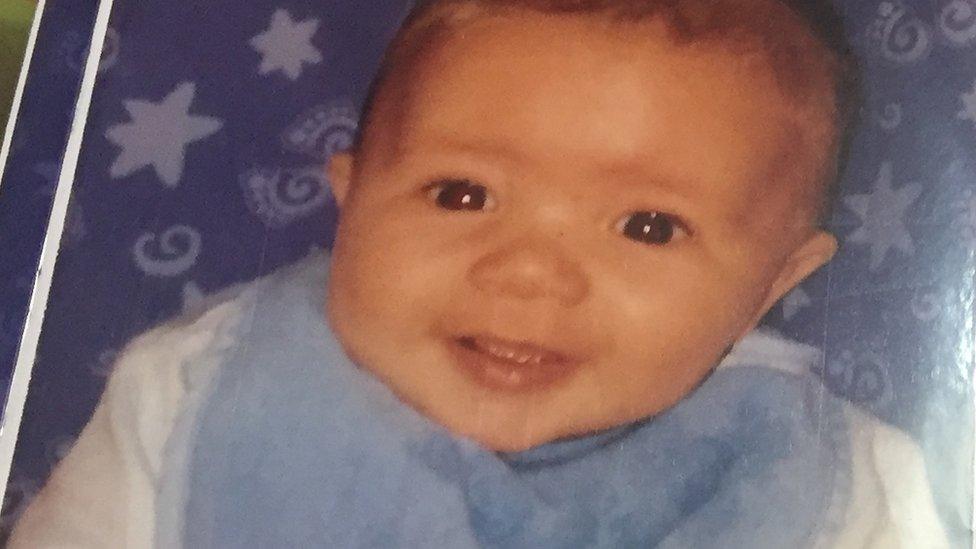

His son Archie, now aged eight, lives with him permanently, and he says he's rebuilding his relationship with Daniella - who's now 18.

A 2016 study, external by the University of Lancaster, commissioned by the Department for Education, suggested that others have successful outcomes from FDAC too.

It found 37% of families were reunited or continued to live together at the end of proceedings - compared to 25% of those who go through ordinary family courts.

However, the sample group was relatively small - 240 families in all.

Archie now lives with John permanently

John says he is now "trying to make up for lost time" with Daniella, who smiles as he says it.

He is grateful for the opportunity.

"I've got two children, I work, I pay my bills, I do lots of fun stuff," he says.

"The way I live my life today is totally different from who I was nearly eight years ago."

Watch the Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel.

- Published18 February 2015