International Court of Justice: UK abandons bid for seat on UN bench

- Published

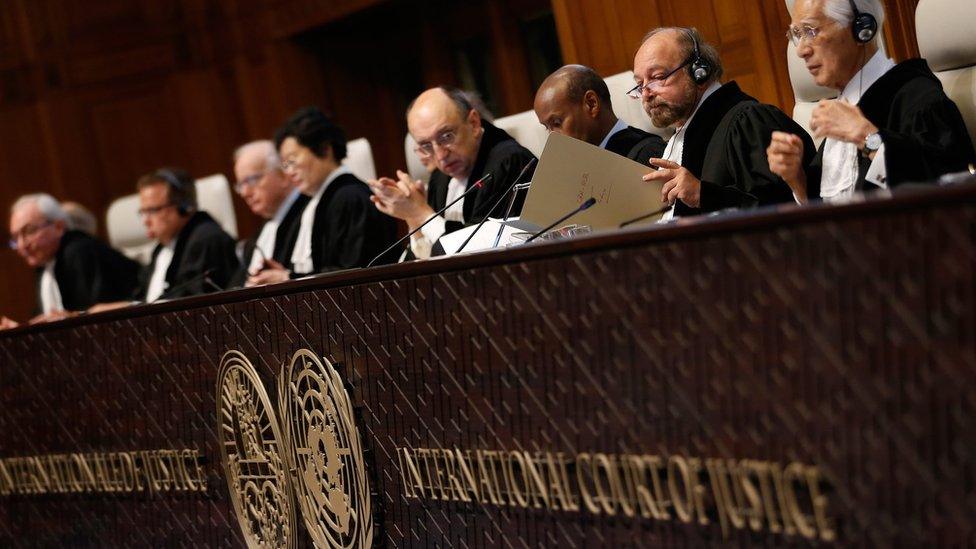

ICJ judges sitting in the Hague in December 2015

The UK is to lose its seat on the International Court of Justice for the first time since the United Nations' principal legal body began in 1946.

Sir Christopher Greenwood was hoping to be elected for a second nine-year term on the bench of 15 judges in the Hague.

The government withdrew his candidacy after six rounds of votes with India's Dalveer Bhandari ended in a deadlock.

Sir Christopher was backed by the UN Security Council but his rival was chosen by the General Assembly.

A successful candidate needs to gain a majority of support in both bodies.

The UK's move means Mr Bhandari will be able take up a position on the ICJ, external, alongside four other judges already elected.

'Close friend'

The UK government had considered invoking a little-known arbitration process but in the end chose to take Sir Christopher out of the race.

The British ambassador to the UN, Matthew Rycroft, said he was "naturally disappointed".

Mr Rycroft said: "The UK has concluded that it is wrong to continue to take up the valuable time of the Security Council and the UN General Assembly with further rounds of elections....

"If the UK could not win in this run-off, then we are pleased that it is a close friend like India that has done so instead. We will continue to cooperate closely with India, here in the UN and globally."

He said the UK would continue to support the work of the ICJ "in line with our commitment to the importance of the rule of law in the UN system and in the international community more generally".

Downing Street refused to confirm that UK Prime Minister Theresa May was involved in lobbying for Sir Christopher to get the job, saying only that representations were made at the highest levels of government.

Analysis: Britain 'in retreat'

By James Landale, BBC diplomatic correspondent

However hard the government tries, this defeat at the UN will be seen as a significant diplomatic set back, a symbol of Britain's reduced status on the world stage.

Britain tried to win an election but the community of nations backed the other side, no longer fearing any retribution from the traditional powers, no longer listening to what Britain had to say.

Some will blame this on Brexit - that might be a little simplistic.

Few countries are as obsessed with Brexit as the UK.

But what is clear is that many countries at the UN were willing to defy Britain and that would have been less likely a few years ago.

The government likes to talk of what it calls "global Britain", a vision of a buccaneering UK, independent of the EU, promoting its interests and values and trade around the world.

The problem is that many believe that vision has not yet been backed up with any policy substance.

Instead, rightly or wrongly, many countries see the UK turning in on itself to sort out the complexity of Brexit.

They see it as a retreat from the international stage - whatever the Brexiteers argue to the contrary - and these countries are filling the vacuum accordingly.

Shift in power

France and Russia, which along with the UK, US and China make up the permanent members of the UN Security Council, have also lost positions recently on UN bodies.

The UN security council is made up of five permanent and 10 non-permanent members

Many members on the General Assembly, which contains representatives from all UN countries, are said to have come to resent the way the Security Council has so much power, particularly the five permanent members.

The so-called Group of 77 - which represent a coalition of mostly developing nations - has long been pushing for greater influence.

- Published20 September 2017

- Published24 August 2017