How fire-safe is British furniture?

- Published

There are few places as frightening to Guillermo Rein as a furniture shop. "I feel very uncomfortable when I go shopping for furniture. Especially if they have a showroom when you can see people moving around sofas".

Professor Rein is an expert in fire science.

He told us at his facility, the Hazelab, external at Imperial College in Kensington: "An enclosure where there's a lot of people and a lot of sofas is something that makes me feel very uncomfortable. It is a nightmare scenario that one of these stores catches fire."

That is because your favourite sofa could be the most dangerous object in your house.

He says the shops always have good counter-measures and escape processes. But Professor Rein cannot help worrying.

That is because the cushions are usually made of combustible plastic foam, and covered in fabric that might be relatively easy to ignite. The combination creates an object that can catch fire and burn hot for a long time.

That is why we regulate furniture materials strictly. Indeed, the UK has some of the toughest rules in the world on furniture fire safety.

Prof Guillermo Rein, head of the Hazelab at Imperial College

Terry Edge was the civil servant responsible for reviewing the regulations until relatively recently.

When he started in the job in the mid-2000s, he said: "I would have said these are the most stringent fire safety domestic furniture regulations in the world - a great success. They are saving lives and you know the rest of the world should really come up to the same level of requirements that we have in the UK".

But Mr Edge is now campaigning against them. "I absolutely don't believe that now."

There are a few concerns about the regulations.

One of the most important relates to how a key test is constructed. Fabric is stretched over a foam cushion made of a plastic that is banned for use in furniture in the UK because it is so flammable. Then the fire resistance is tested.

The choice of this super-combustible foam is contentious: defenders of the test argue that it means it creates a "margin of error" because the test is so hard to pass.

But to get through the test, most manufacturers meet the requirements by treating a lot of their fabrics with flame retardants - chemicals that help to prevent ignition or slow the spread of fire.

The Grenfell Tower fire is an apt moment to consider the wisdom of this approach. After the disaster, a dozen residents were treated for cyanide poisoning.

All smoke is bad for you, but the most common flame retardants used in furniture work by interfering with the chemistry of burning. That means that once there is a fully developed fire, they make the smoke more toxic - increasing the volumes of carbon monoxide and hydrogen cyanide, in particular.

New research published this month in the science journal Chemosphere by authors including Richard Hull, professor of Chemistry and Fire Science at the University of Central Lancashire, suggests that these fire retardants makes the fire much more toxic, external - and do little to hold back flames.

Prof Hull explained: "We burnt two kinds of sofas: UK furniture flammability regulations sofas with flame retardants and a European sofa without flame retardants and we found that the UK sofa burnt slightly slower than the European sofa but in doing so it produced between two and three times as much toxic gas as the European sofa."

Prof Richard Hull of the University of Central Lancashire

It is unclear how worried we should be about the increase in smoke toxicity. Prof Rein argues that, even if it makes smoke less toxic, we should very wary of changes that might decrease fire resistance. Since all smoke can incapacitate and kill, the critical way to prevent all smoke deaths is to prevent fire.

He thinks that a focus on preventing ignition is the critical way to save lives - and if we make smoke less dangerous but have more fires, this is probably not a price worth paying.

Smoke toxicity, though, is not the only issue.

Last year the government noted that 'flame retardant chemicals, particularly brominated flame retardants… can be harmful to human and animal health' and noted that some popular types are set to have their use restricted by the EU for that reason.

This concern is one reason why the US has already been fighting over their use for some years.

Arlene Blum of the Green Science Policy Institute, explains "flame retardants are what are called semi-volatile. That means they are coming out, always, from the couch. You don't have to sit on it, they're always coming out. And they're heavy, they drop into dust. You get dust on your hands and you eat a sandwich - you're eating flame retardants."

"Cats who groom their fur have 10 to 100 times higher levels than humans."

In the US, there has also been concern about whether these chemicals contribute to elevated rare cancer incidence among firefighters. This is an established area of controversy in America: the Chicago Tribune has been investigating this topic, external for some time and it was scrutinised by the documentary Toxic Hot Seat, external.

Arlene Blum of the Green Science Policy Institute

Prof Hull's research also raises a question about whether the regulations actually prevent fires: his research found British sofas burned at a similar rate to European ones.

But his research is not the first to raise concerns about the rules' effectiveness. At the moment, our regulations only apply to certain parts of the sofa. The arms of a sofa, for example, often contain hessian, wood or cardboard which is an unregulated fire risk.

Furthermore, data that would show Britain actually has fewer fires as a consequence is hard to find.

Last year the French agency for Food, Environmental and Occupational Health and Safety, external concluded that the effectiveness of our furniture regulations was difficult to assess because of the role of other factors like the reduction in smoking and the increased use of smoke detectors. Rather than adopt standards from across the Channel, the agency recommended a series of measures to reduce fires without exposing the whole population to the chemicals.

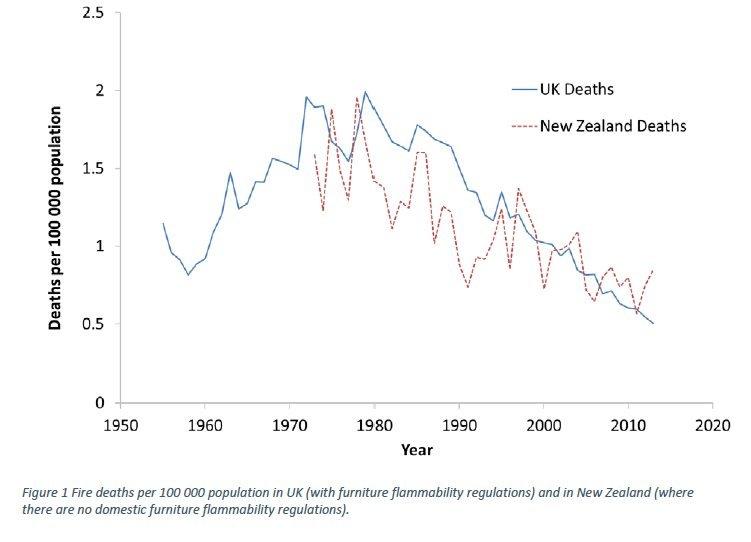

Prof Hull's research notes that while our fire deaths have declined since the late 1980s, they are not unusual in having done so. Our decline matches that in New Zealand, for example, which has had no changes in furniture rules. The rise of smoke alarms and the decline of smoking accounts for much of the decline.

Graph comparing UK and New Zealand fire deaths

Here in the UK, advocates for the regulations point to research commissioned by the government in 2009 which found that the reduction in the rate and lethality of furniture and furnishing fires was estimated to equate to 54 lives per year, external. This particular figure, from a lengthy piece of work, has been cited repeatedly, and is the preferred measure of advocates of the regulations.

But the University of Cambridge statistician Professor David Spiegelhalter queries the sums involved in arriving at the number. He suggests a figure more like 20 lives saved per year. They had, he believes, double-counted lives saved.

The authors of the "54 lives" report told us their estimates should not be treated as literal or exact values but that they had found strong statistical evidence that furniture fire and casualties declined more than other fires and that the regulations had an effect over and above other factors.

Prof Rein, who has done research work for chemical companies, supports tough rules in favour of higher flammability standards, which might entail or encourage retardant use. But he says the data and research remains crude in a field that is poorly funded. "When you look into medicine, for example, I envy them tremendously... We have three studies per topic instead of 3,000 - which is the level of studies you would require to actually inform the politicians."

The European Flame Retardants Association, a trade body, pointed us to research, commissioned by an NGO it funded. Their work concluded that within the first five to seven minutes of ignition, UK sofas have superior fire resistance over European sofas.

This is a policy area where we have competing risks - on the one hand, we do need to make sure that sofas are as fire-safe as possible. On the other hand, we want as few flame retardant chemicals as possible; they are nasty chemicals and make fires, once they break out, more lethal.

But we fund research into these dangers in ways that make them hard to compare and weigh against one another. So how did the UK end up deciding on these rules?

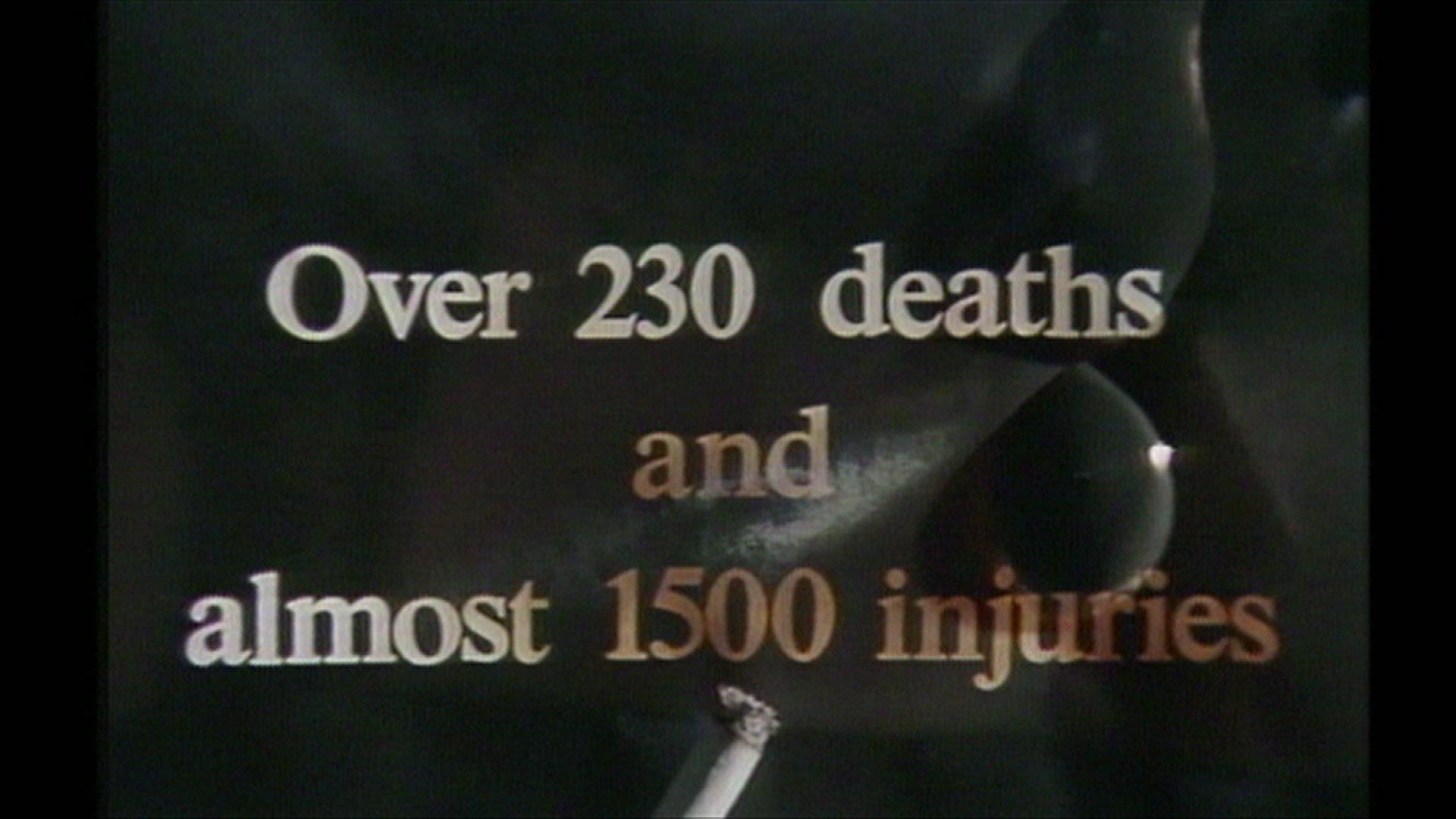

A still from a public information film on the human cost of fires caused by smoking

The story starts in the 1980s when there was growing concern about house fires - in part because we used a lot of horrifyingly flammable foam padding in chairs and smoking was also much more prevalent.

As part of a report into house fires caused by cigarettes in 1985, Newsnight interviewed Bob Graham, a leading firefighter from Manchester. He had been involved in fighting a major furniture fire at a Woolworth's in 1979 which deeply affected him.

Back then, he told us: "We've got a situation where we have the smallest ignition source in the home being responsible for the largest proportion of deaths and it's avoidable." He was referring to cigarettes.

The tobacco companies refused an interview to Newsnight at the time - but we know they were watching. Newsnight has dug up internal memos, released as a consequence of American legal action, which show the concerns of the industry lobby group.

One document, from 1986, external, notes: "The Tobacco Advisory Council's inability to put forward a defensible PR stance on the so-called self-extinguishing cigarette issue was amply demonstrated by TV and press comment in July 1985" (when the Newsnight piece aired).

They argued that they needed to build "a protective ring of support around the industry against public criticism" - and, suggested following the route adopted by Big Tobacco in the US. A key to their success in America had been recruiting senior firefighters to their cause, external.

Mr Graham - the firefighter who appeared on Newsnight - was seen as a potential "spark plug", external to 'consider involving in public education of public awareness efforts'.

Mr Graham told us this month that he wasn't aware of having been approached or lobbied by any tobacco companies. He certainly wasn't paid by them. "I was in the fire service and you wouldn't be allowed to do anything like that. You couldn't deal with any businesses whatever they were."

Nevertheless, he switched to thinking that fixing furniture, not cigarettes, was the answer: the tobacco documents show he was concerned about the feasibility of developing self-extinguishing cigarettes speedily. Tobacco won the argument nationally, too.

In 1988, the modern fire regulations were passed - and the cigarette companies had got what they wanted. Britain was focussed on furniture, not cigarettes. So, they wrote, external, their fire safety group "self-extinguished, with a view to keeping a watching brief and commenting as necessary."

The Tobacco Advisory Council is now called the Tobacco Manufacturers' Association. When we put all of this to them they said: "all cigarette products placed in the UK market have for a number of years included design modifications which make the cigarette more likely to self-extinguish when left unattended."

Bob Graham, then a Manchester fire fighter, on Newsnight in 1985

That wasn't the end of the lobbying, though.

Mr Graham - having retired as a firefighter - was approached in the late 1990s by a PR company, Burson Marsteller. "They said we'd like you to raise fire awareness in Europe. And I said: 'Okay - but I'll do it my way.'" And so the Alliance for Consumer Fire Safety in Europe was born.

The PR company chose a punter-friendly name, but it was being funded by a committee of the fire retardant makers active in Europe.

They also, briefly, had a member called the National Association of State Fire Marshals. Again, this sounds like an official American fire officers' association. But it was led by a man called Peter Sparber, who was well known to people involved in this argument in the US.

Prof Blum, who campaigned against the use of retardants, said: "Peter Sparber was in the Tobacco Institute [the lead tobacco industry lobbying body in the US] and he led for a number of years the National Association of State Fire Marshals. They worked against fire-safe cigarettes, which really do save lives, and they worked for flame retardants."

Mr Graham confirmed they played a small role in his organisation: "We saw them probably three times in 15 years," he told us.

"Now and again we fell out because they were trying to push me in a particular direction, get flame retardants into products that didn't present a fire hazard."

Mr Sparber has been approached for comment.

The Alliance did enjoy some success, persuading manufacturers like Sony and Philips to make televisions sets that could resist being set alight by candles. But the real prize of getting the rest of the EU to adopt the UK's tough standards on furniture - standards which have the effect of encouraging manufacturers to use a lot of flame retardants - remained elusive.

And in 2014, when the UK announced a review of its furniture regulations, the chemical companies' key redoubt - Britain - came under threat.

Terry Edge, former head of review of UK furniture regulations

Concerns about the volumes of retardant in British homes are what motivated Mr Edge, who initiated the review.

He proposed two major changes. First, the sort of foam actually used in the test should be the sort of foam used in furniture - not the hyper-flammable foam used at present. That would cut the amount of retardant required.

Second, they proposed testing more parts of the furniture, increasing the volume of material that would need to be checked and certified. That would deal with the problem of highly flammable structural material being used to prop up sofa arms, for example.

Mr Edge expected some push-back. But he soon discovered it wasn't just flame retardant companies that were resistant to change. There is a large competitive advantage for UK furniture manufacturers and retailers from the current rules.

Mr Edge said: "The furniture industry really likes these [current] regulations because they are barriers to trade because it gives them a huge advantage in the home market. If you're a German manufacturer and you want to sell furniture into the UK, you have to create a separate range that complies with our regulations."

In short, it makes it harder for companies like IKEA to compete - no small issue when the company estimates it already has 10% of the UK market.

IKEA was in favour of reform - but the industry trade bodies were not. While some furniture companies supported reform, there was a bigger wave of resistance to it.

There were reasoned objections. One concern, in particular, was that the need to regulate more parts of the furniture might lead to retardant being required in more places to pass tests - to the extent that it would outweigh the reductions in flame retardant elsewhere.

That is a reason why the Furniture Industry Research Association (FIRA), an industry membership body whose research was referred to in many responses to the consultation, opposed the changes. But they also told us they thought the UK rules needed a 'full update'.

Furniture prior to 1988 was allowed to use much more flammable foam for cushioning

Mr Edge became keenly aware, in particular, of the work of Conservative MP Stephen McPartland, chair of the All Party Parliamentary Furniture Industry Group. This particular APPG is seen by the furniture industry as a way of lobbying government.

A few years before this consultation opened, in 2012, FIRA sent a report, external to their members stating that they do "all" of their lobbying via the British Furniture Confederation, the body that provides Mr McPartland with a secretariat to help him run the APPG. (On his LinkedIn profile, the former chair of the BFC lists his role as having included "influencing legislation through the All Party Parliamentary Group at [the] House of Commons".)

The FIRA document also said the BFC was "pleased" with the "progress made due to the work of the APPG … under the excellent leadership of Stephen McPartland MP". Their top-listed "significant achievement" back then, a few years before the consultation opened, was in "resist[ing] the EU pressure to dilute the British flammability regulations."

Mr McPartland's image is pictured under the title "Lobbying on your behalf". The Stevenage MP was emailed shortly after the consultation period closed by a furniture industry trade body asking Mr McPartland to take up this issue with Jo Swinson, the minister then in charge.

In December 2014, two months later, Mr McPartland was appointed a non-executive director of the UK's largest independent furniture retailer, Furniture Village. He is currently paid £3,666 a month for his role at the company, which takes 10 hours a month.

When asked about these arrangements, Mr McPartland stated that Mr Edge was disgruntled. He added: "I do not lobby Ministers, I am a Member of Parliament, not a lobbyist." Furniture Village, he said, "is a retailer, not a manufacturer and imports products globally". He added that he is not responsible for what other people write, and that our questions showed "zero understanding of the industry".

Page 8 of the Furniture Industry Research Association annual report 2011-12

In the end, the business department did not take Mr Edge's reform proposals forwards. The department said: "We have sought views, consulted and proposed ways forward but there is not yet consensus across the sector and Government will not take risks with people's safety."

A consensus is politically important. Anything that can be characterised as reducing fire resistance will, in the current climate, be a hard sell.

But building a consensus is difficult - precisely because of the duelling commercial interests.

As Prof Hull says, "The standards process in the UK is dominated by people who can afford to attend the meetings and those are usually people with a vested interest in a particular outcome".

The government held another consultation on this issue last year - and have yet to respond to the replies.

Mr Edge says opponents of reform are keeping in place a test regime that's been shown to be unfit for purpose. But some fire scientists, like Prof Rein, are concerned about any reforms that would reduce the fire resistance of fabrics.

So what can government do? If it is to make its mind up, it needs to do research of a sort that does not currently take place.

The fact that some material used in furnishings is unregulated may be undermining the fire safety of most of our furniture. We do not know by how much.

We may be saving a few people from fire, but at the cost of harming many more people by exposing them to bioaccumulative chemicals. We cannot now gauge the balance of risks.

Answering questions about the importance of smoke toxicity also requires work on how fires kill at the moment. We do not know how many lives are saved from slowing or preventing ignition, as opposed to being able to flee later when the fire is mature.

Answers to these question might end up with a complex solution: more parts of our furniture might need to be tested and treated to a high standard, but the range of chemicals permitted for use could be limited.

We have reduced risk in our homes with smoke alarms and a reduction in smoking - but, each year, we increase the risks by introducing more flammable polymers into the British home. We are continuously making our living environments more combustible.

Government should take fire more seriously.