Was 2017 the worst year for UK terrorism?

- Published

Mourners at the makeshift memorial in Manchester's Albert Square, following the attack there

Over the past year there has been a surge in terrorism plots, attacks and arrests in the UK, but is it the worst ever year on record?

The short answer is that it is nowhere near as bad as it was during the height of The Troubles in Northern Ireland - and it's not the worst year on record for fatalities either.

But a broader measure of counter-terrorism activity suggests that 2017 was indeed the most challenging year for the police and security services for decades.

The worst single year of The Troubles was 1972 in which 470 people died, external and almost 5,000 more people were injured.

The police also recorded 1,382 explosions and seized more than 180,000 rounds of ammunition.

Last year's attacks at Westminster Bridge, Manchester Arena, London Bridge and a mosque in north London killed 36 people.

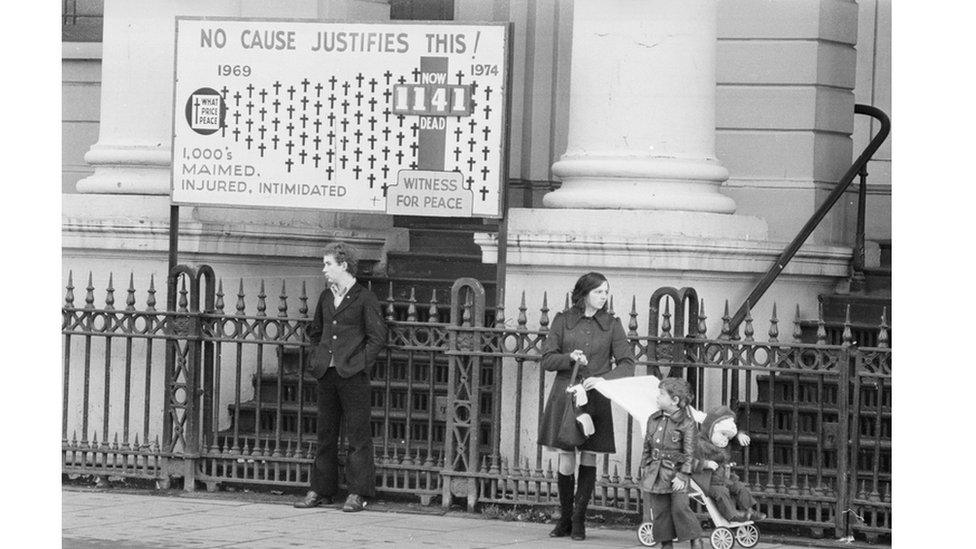

A peace campaign poster in Northern Ireland in 1974

The most deadly single year of this century remains 2005 because of the 52 people killed by the four suicide bombers who carried out the 7/7 attacks.

Going back further, the 1988 Lockerbie bombing - in which a Pan Am passenger jet en route from London to New York was blown up over the Scottish town - killed 270 people, including 11 victims who were on the ground.

But the director general of MI5 Andrew Parker recently said that the tempo of counter-terrorism operations was the highest he had seen in his 34-year career.

So what does that actually mean - can we measure it?

3,000 'subjects of interest'

MI5 is running approximately 500 live operations involving 3,000 "subjects of interest" - the jargon for a suspected extremist. Those figures aren't particularly informative because we don't get regular data to compare them against.

The latest report, external from Parliament's Intelligence and Security Committee, published just before Christmas, adds some rather important detail about the rising volume of "high-risk casework" that MI5 is managing.

These are cases where the suspect has some kind of training, perhaps in bomb-making, or is attempting to move closer to carrying out an attack, even if they have not yet come up with a final plan.

"Previously, these sorts of cases represented a smaller share of MI5's work, with a greater proportion of cases being 'slower burn' in character and requiring less resource-intensive monitoring," said the committee.

We obviously don't see a lot of that casework - but we do see the quarterly statistics on arrests - and these are a very strong indicator of the level of behind-the-scenes activity.

Arrests can follow months of intensive investigations into networks of extremists. For every arrest there may have been many other potential suspects whom the security services have looked at.

In other words, arrests are the public tip of the secret counter-terrorism iceberg.

The 7 July attacks memorial in Hyde Park, London

There were 400 arrests on suspicion of terrorism-related offences in the year to the end of September 2017. That's the highest recorded figure, up more than 50% on the previous year.

There have been more arrests since then, so if you accept the level of police and MI5 activity as a measure of the threat, then the past year is the worst on record.

Overall, there were 78 prosecutions - a figure that includes arrests from the previous year - and that is up 16% on the previous 12 months. Nine out of 10 of those charged were convicted.

And that means there are more people in jail - some 215 people - a quarter higher than the previous year.

About half of those arrested over the past year were released without charge, including the 56 who had held as part of the investigations into the London and Manchester attacks.

That is not an unusual rate for terrorism-related investigations. Police will very often arrest family members or close friends if there is any hint that they knew of a prime suspect's plans.

Does all of this translate into anything more tangible? Can we report with any degree of accuracy the number of actual plots that have been stopped?

The latest official figure, from December, is that nine Islamist plots had been foiled, external since March 2017 - and 22 since 2013, when the Islamic State group emerged in Syria.

There is no public list of these plots because some details may be at a highly sensitive stage of investigation or the cases are already before the courts and therefore unreportable until trial.

We keep our own tally of plots at the BBC - although we can't report them all yet - and we can't argue with the government figures.

Last year we counted three alleged plots leading to the most serious charges. This year we have tracked charges relating to preparing acts of terrorism in nine alleged Islamist cases. If we include the separate category of alleged far-right plots, we get to 11 major investigations.

So 2017 was a bad year for attacks, while still nowhere near the levels of The Troubles in Northern Ireland. But it definitely looks like there has been an unprecedented level of activity around tracking down people who are suspected of wishing to do harm to others.