Sofa surfers: The young hidden homeless

- Published

Sam: "It takes pretty much every day of my life, trying to find out where I am going to be staying"

Sam does not know where he will be sleeping tonight.

Now 23, he says he first became homeless at 15 because of a family breakdown and has been in and out of bedsits, hostels and supported accommodation ever since.

"I've stayed at friends' in the past - I've never really had my own actual flat," he says.

"I've slept rough quite a few times but most of the time when I've slept rough I have not actually slept.

"I just wander round because I can't really shut off when I'm out in the cold."

Floors and settees

This week a committee of MPs called homelessness a "national crisis", highlighting more than 9,000 rough sleepers and 78,000 families in temporary accommodation in England alone.

Sam drifts between friends' sofas, temporary accommodation and rough sleeping in and around Leyland in Lancashire. Young people like him do not always show in official statistics - but new UK-wide research for the BBC found:

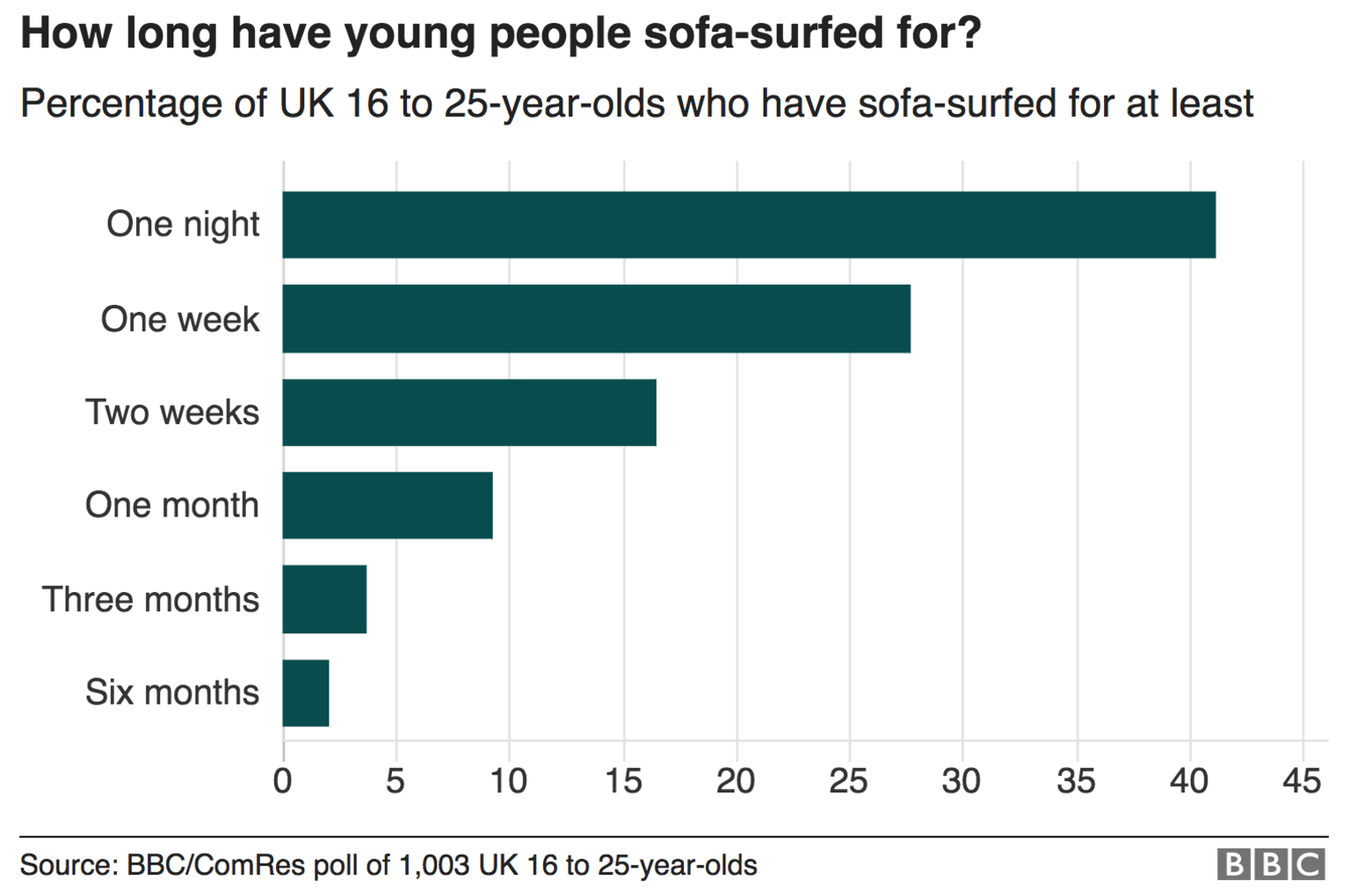

41% of young people have stayed with friends on floors or sofas for at least one night (excluding after nights out or due to travel difficulties)

Just over 9% did so for over a month

Young men are more likely to have sofa-surfed than young women - 48% of the 484 men questioned said they had compared with 34% of 519 women.

At The Key drop-in centre for young homeless people in Leyland, Ian, 25, says he has been sofa-surfing for seven years.

His days revolve around a few hours at the drop-in centre.

Otherwise, he walks the streets for hours, trying to stay warm and then heads to a mate's house in the evening.

"I end up spending a few hours there. Then I would finally ask him if I could stay the night. If he says yes I would stay there."

He says he feels a burden on his friends.

Sometimes he says he runs out of friends he feels able to ask and has to sleep out.

Sub-zero respite

The most common reasons for young people resorting to friends' sofas included parents being unable or unwilling to provide housing, extended family being unable to help and splitting from a partner.

Tenancies ending, domestic abuse, rent arrears and leaving care also contributed.

On the phone, looking for a room

Ian has been offered a friend's flat for the next three weeks.

Sam, who has spent time in prison, has come to the drop-in centre to make calls to try to find a room for the night.

On the coldest nights, the local council will find him somewhere to stay but that ends as soon as the temperature rises above zero.

"It takes pretty much every day of my life, trying to find out where I am going to be staying.

"It doesn't feel like it ever ends. I feel quite drained with it all."

He is on medication for depression. Sam says not having an address means he can't register with a GP to get the mental health support he needs.

Depression affects Ian too and both young men say it's hard to study or look for work without an address.

"I feel like I'm going round in circles and circles and circles," says Ian.

"All I can do is keep trying."

'Everybody's got strengths'

Ursula Patten, operations director at The Key, says sofa surfers should definitely be considered homeless.

"You are homeless if you haven't got a place you can stay on a consistent basis - somewhere that you can call home."

She says about 70% of the homeless young people on the charity's books have sofa-surfed before running out of options and seeking help.

But she believes that with the right support there is no reason why homeless young people should not have hope for the future.

"It's just a phase in your life. You may have got lost but you've got strengths. Everybody's got strengths. And I would say go and get some support and somebody to help you find your direction in life because you can attain great things."

Charity support includes emergency food parcels for young homeless people

The charity Centrepoint said the BBC data corroborated its own research, carried out in 2014 by Cambridge University., external

Co-author Anna Clarke said: "Sofa-surfing is a not uncommon experience for young people in housing difficulties.

"It is really useful to have this kind of evidence on something that's inherently difficult to quantify."

And Centrepoint chief executive Seyi Obakin said it was crucial to "dispel the myth that there is anything fun or easy about sofa-surfing".

Five things about being homeless

"Goodwill is the only thing keeping too many young people from sleeping on the UK's streets.

"It's frightening just how many are trapped in a cycle that is detrimental to their health, sees them struggle to keep up in education, and where outstaying their welcome can mean becoming exposed to dangers no-one should have to face."