What now for UK-France security relations?

- Published

RAF helicopters to Mali, French troops to Estonia, spy chiefs sharing intelligence. When it comes to defence and security, the Anglo-French entente cordiale has rarely been closer as their political leaders meet for their annual summit.

Building on the Lancaster House agreement of 2010 between the two countries' then leaders, David Cameron and Nicolas Sarkozy, a landmark summit is now being held between Theresa May and President Macron of France.

With the UK's looming departure from the EU, Brexit, trade and migration will inevitably feature in their discussions.

The French president has been pushing for Britain to accept more migrants from Calais and to pay more towards the upkeep of the two countries' joint Channel border controls.

Historically, this annual summit has always been about security and this year is no exception.

The continuing threat from the Islamic State group, the conflicts in Syria, Afghanistan and West Africa, Russia's actions in the Baltics and Ukraine and the emergence of transatlantic differences over certain key issues such as Iran, are all reminders of the need to shore up bilateral ties between London and Paris, ahead of Brexit.

Britain may be leaving the EU but it will remain a heavyweight partner for France when it comes to security issues.

French political analyst Dominique Moisi says: "We are close allies and we are rivals - and precisely because the UK is leaving the EU we may be even more rivals.

"But the international context forces us to come closer to resist terrorism because of the vacuum left by the US."

So, what are the defence and security issues up for discussion at Sandhurst?

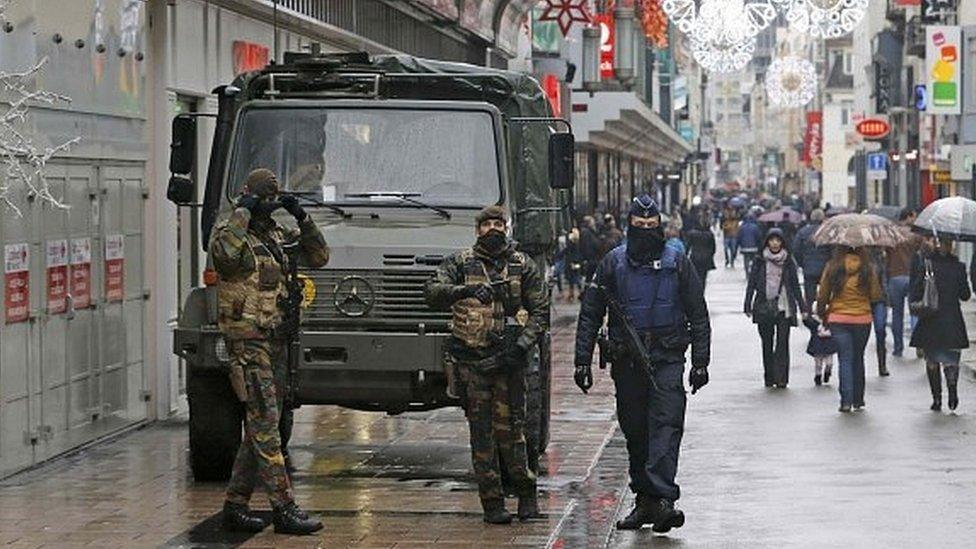

Counter-terrorism

Britain and France have an incredibly close partnership in confronting the shared threat of terrorist attacks inspired or directed by so-called Islamic State.

So close, in fact, that this is the first ever meeting of "The Quint" - the heads of all five British and French spy agencies, both domestic and foreign. They will be discussing, among other things, the lessons learnt from last year's terror attacks in Manchester, Barcelona and London.

There is a permanent 'open door' for French intelligence officers who need to visit MI5 headquarters at Thames House in London and a similar arrangement exists for British case officers visiting France's equivalent, the Direction Générale de la Sécurité Intérieure (DGSI). MI5 officers were rushed to Paris in the wake of the 2015 Bataclan attack to help follow up intelligence leads and glean any possible lessons.

As well as bilateral links like this, the primary mechanism for sharing intelligence between European partners is the Counter Terrorism Group (CTG). Heads of European agencies meet at least once a year, their subordinates more often.

The concern over Brexit has long been the risk that Britain could be denied access to certain EU bodies, such as Europol. In fact, say insiders, the business of counter-terrorism is likely to continue as usual.

Sir Julian King, EU Security Commissioner in Brussels, told me in October that the terrorist threat facing all of Europe was so great that no-one wanted to take any risks by reducing counter-terrorism cooperation with London. Theresa May, who was Home Secretary for six years until she became PM in 2016, will be keen to see this intelligence-sharing with Paris maintained and even increased.

Lord Peter Ricketts, who was both national security adviser and then UK ambassador to Paris until 2016, says Anglo-French co-operation has improved dramatically since 2000.

"From what I saw as ambassador in Paris, the two counter-terrorism communities and law enforcement communities are now finding they've got things to learn from each other so it is not nearly as polarised as it was 15 years ago," he said.

Defence

Despite recent UK defence cuts, Britain and France remain far ahead of other European nations when it comes to deploying combat forces overseas.

In Mali and other Saharan nations, French forces have been battling a jihadist insurgency for five years. They've asked for British help, and now they are about to get it.

Britain is to send three RAF Chinook transport helicopters to support the French operation in Mali, along with 50-60 support staff.

French political analyst Dominique Moisi says: "France wants to share responsibility with other European powers, convincing them that the Sahel is becoming a primary objective in the fight against terrorism, as it is receding in Syria and Iraq after the defeat against ISIS."

As if by way of return, France is to send troops to join the UK-led battle group in Estonia where 800 British soldiers are helping to guard Nato's eastern flank with Russia.

This is all part of a growing military alliance between Europe's only two nuclear powers and permanent members of the UN Security Council.

The two nations are working on a joint Unmanned Aerial System for future drones. A French Brigadier was put in charge of a UK division for two months while a British Army Brigadier did the same in France. Joint exercises are being held with a view to building up a combined intervention force of 10,000 troops by 2020.

There is a precedent for that, which did not end well: Libya.

The Nato air campaign in 2011 was initially successful, driving back the forces of Colonel Gaddafi which threatened to massacre the residents of Benghazi. Mr Cameron and Mr Sarkozy were briefly feted as saviours of that North African nation.

Thereafter Libya deteriorated into chaos, and Western nations were reluctant to get drawn into any kind of occupation role after the experience in Iraq. So the end-result of any future interventions, whether in the Middle East, Asia or Africa, will need to be very carefully thought out.

Intelligence

The cross-channel co-operation on domestic counter-terrorism is matched to some extent by the links between MI6 and its French counterpart, the DGSE.

The UK's closest intelligence-gathering partner remains the US but it also has strong bilateral arrangements with France, Germany, Spain and other European nations' agencies.

A former British intelligence officer says that old Anglo-French rivalries overseas had given way to shared goals.

He said there was a common desire for Britain's expertise, such as in cyber, to remain accessible to European agencies after Brexit, effectively ring-fencing intelligence and counter-terrorism from ongoing arguments in other areas such as trade and migration.

There is Brexit, says a Whitehall insider, and then there is security.

- Published19 January 2018

- Published29 November 2017