Carillion: Six charts that explain what happened

- Published

The collapse of construction giant Carillion has put thousands of jobs at risk across the UK. Here are six charts and maps that tell the story of the firm's demise.

1. Carillion employed a lot of people

Carillion may not have been a household name, but it employed 43,000 staff globally, around half of these in the UK.

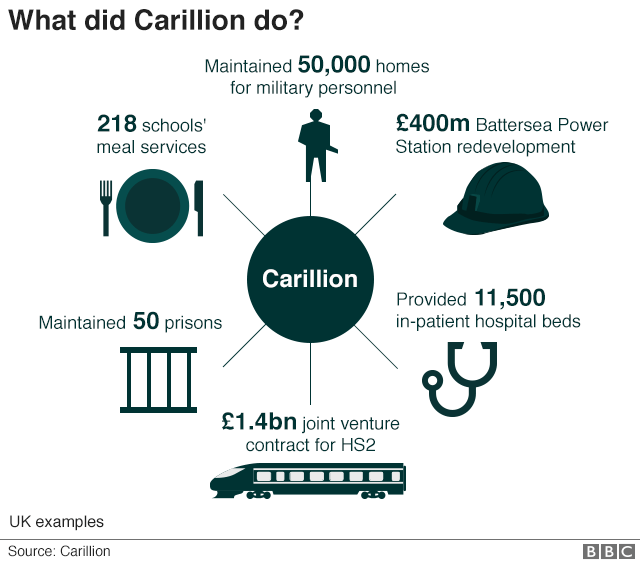

Describing itself as an "integrated support services business", it held about 450 governmental contracts, spanning the UK education, justice, defence and transport ministries.

It managed the Smart Motorways traffic control system and supplied school dinners as well as maintaining about half of the UK's prisons and Young Offender Institutions. Its responsibilities included cleaning, landscaping and catering.

Carillion was the second-biggest supplier of maintenance services to Network Rail.

It also operated in Canada, the Middle East and the Caribbean and was a big supplier of construction services to the Canadian government.

The UK government has said staff and contractors working on public sector contracts will continue to be paid.

Carillion: What is it and what's happening?

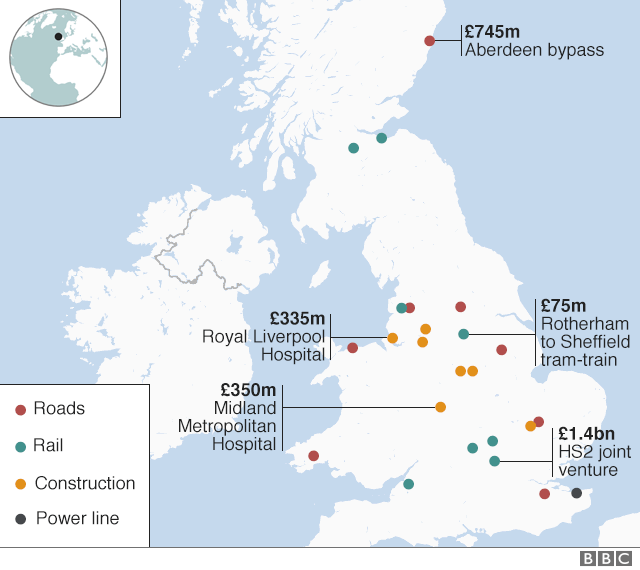

2. It had major construction projects across the UK

Carillion's building contracts spanned the country.

They included the planned HS2 high speed railway line, the Royal Opera House, the Library of Birmingham, the Tate Modern, and the hoop-shaped building of GCHQ.

Three troubled and delayed projects - the Midland Metropolitan Hospital in Sandwell, the Royal Liverpool Hospital and the Aberdeen bypass - eventually contributed to the company's demise.

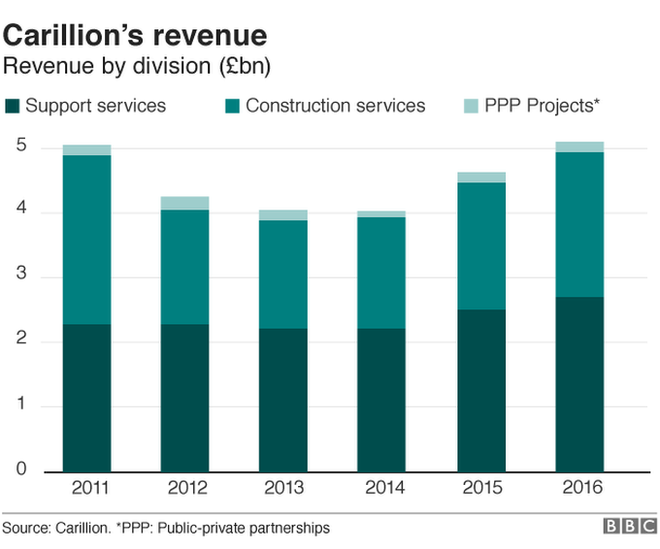

3. Its finances looked healthy - until recently

In 2016, Carillion had sales of £5.2bn and until July boasted a market capitalisation of almost £1bn.

But it ran into trouble after losing money on big contracts and running up huge debts.

Some argue that it overreached itself, taking on too many risky contracts that proved unprofitable. It also faced payment delays in the Middle East that hit its accounts.

Last year, it issued three profit warnings in five months and wrote off more than £1bn from the value of contracts.

This made it much harder for the company to manage its debts and pension deficit.

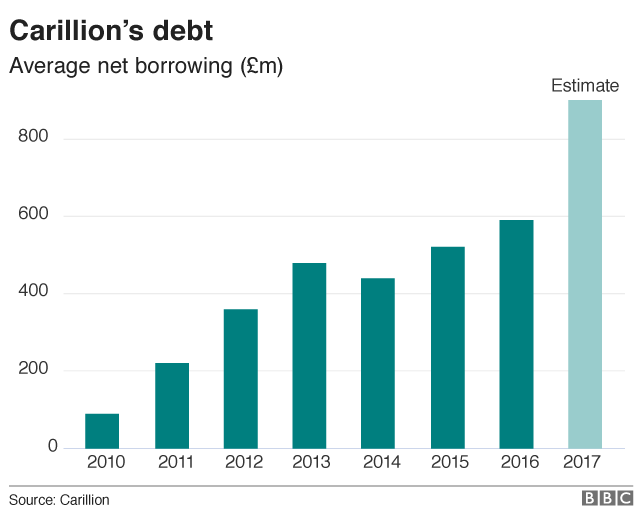

4. The company collapsed under £1.5bn debt

The firm finally buckled in January 2018 under the weight of a massive £1.5bn debt pile.

Despite discussions between Carillion, its lenders and the government, no deal could be reached to save the company.

Its biggest problems were cost overruns on three UK public sector construction projects:

The £350m Midland Metropolitan Hospital in Sandwell: opening delayed to 2019 due to construction problems

The £335m Royal Liverpool Hospital: completion date repeatedly pushed back amid reports of cracks in the building

The £745m Aberdeen bypass: delayed because of slow progress in completing initial earthworks

In December, the firm convinced lenders to give it more time to repay them.

But the company's banks, which include Santander UK, HSBC and Barclays, were reluctant to lend it any more cash.

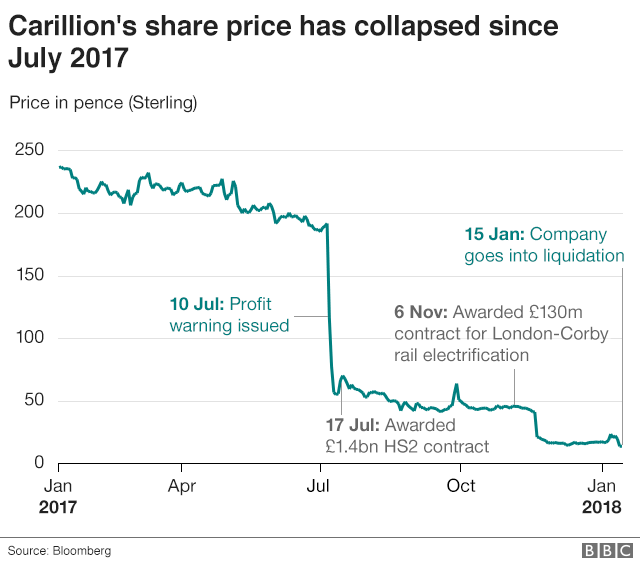

5. The share price fell off a cliff

Carillion's share price plummeted following the first profit warning in January last year, then dropped further as more warnings were made.

Large contracts were awarded to the firm during the period those warnings were being made and the company was known to be in financial difficulty.

The company was left with just £29m before going bankrupt.

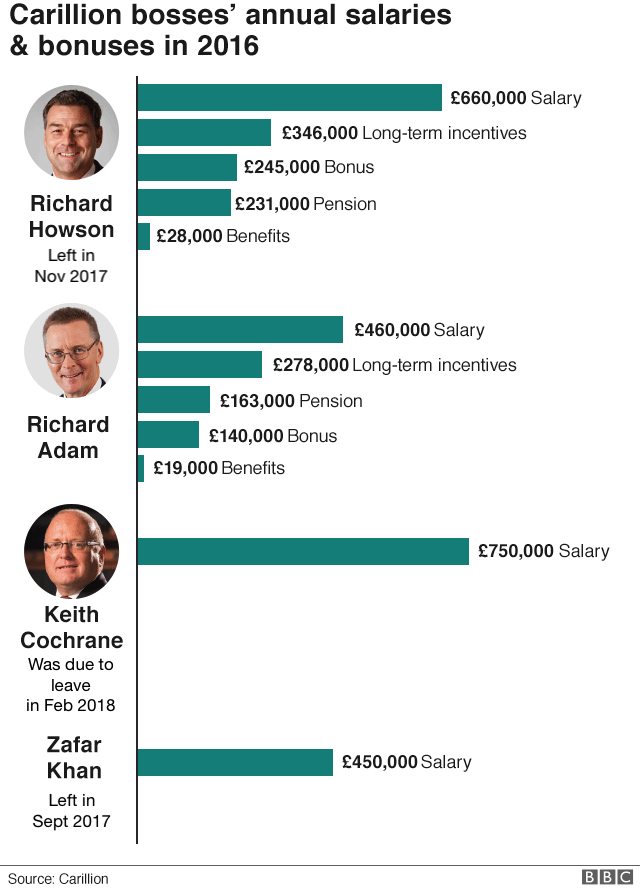

6. The firm's bosses were earning a lot of money

Former chief executive Richard Howson, who headed the company from 2012 until July 2017, earned £1.5m in 2016, which included £245,000 in bonuses and £231,000 in pension contributions.

As part of his departure deal, Carillion had agreed to continue paying him a £660,000 salary and £28,000 in benefits until October 2018.

A similar deal was struck for former finance chief Zafar Khan, who left Carillion in September and was set to receive £425,000 in base salary for the following 12 months.

Interim chief executive Keith Cochrane was due to be paid his £750,000 salary until July, despite being due to leave next month.

However, the UK government has said no bosses and directors of Carillion will be receiving such bonuses or severance payments.

The Insolvency Service confirmed no such payments had been made since the construction firm collapsed this week.

Executives are often granted a lengthy paid notice period. The UK Corporate Governance Code stipulates that they should be "set at one year or less", but that new directors can be offered longer periods.

- Published15 January 2018

- Published15 January 2018

- Published17 July 2017