Ten charts on the rise of knife crime in England and Wales

- Published

After falling for several years, knife crime in England and Wales is rising again. So what is happening?

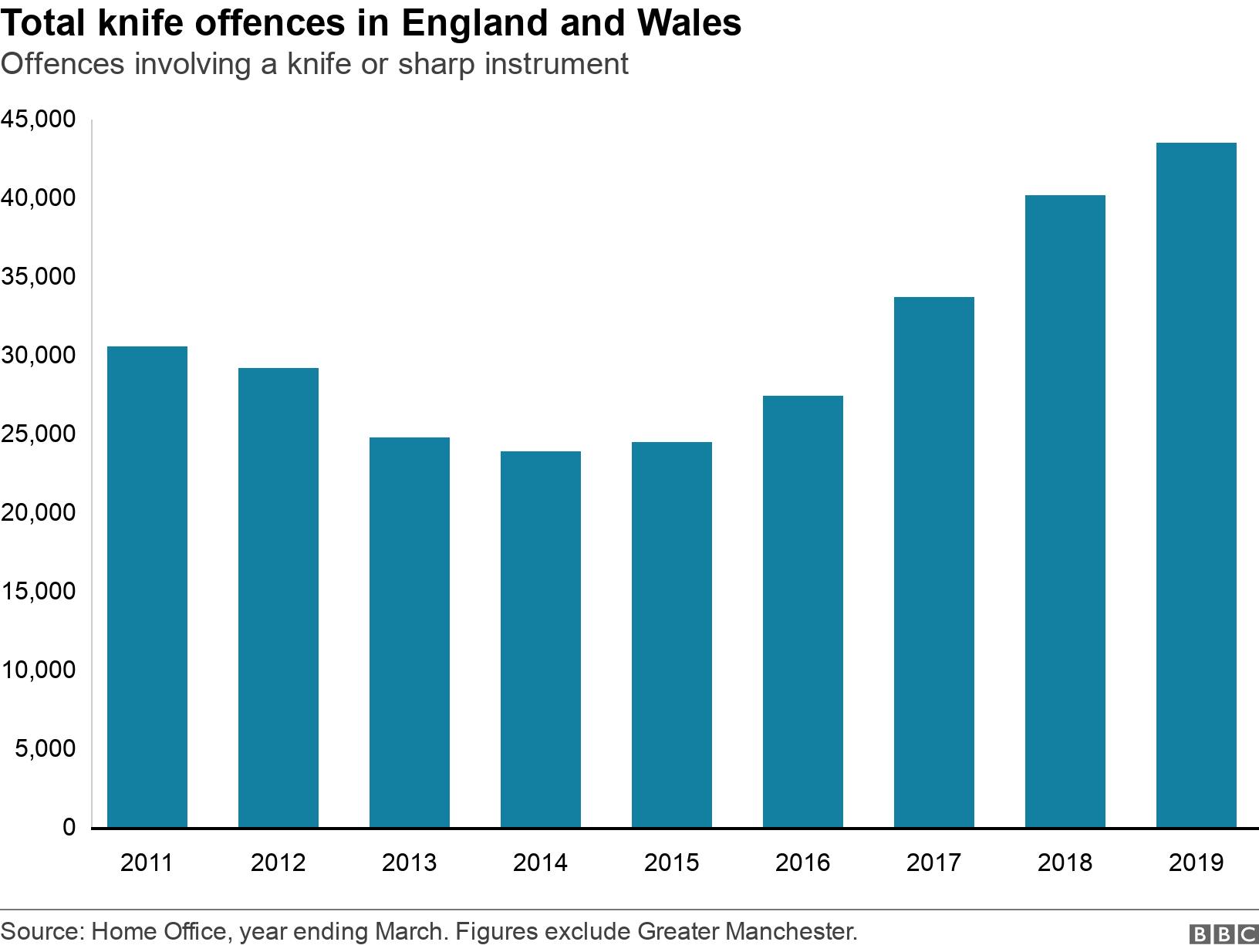

There were 43,516 knife crime offences in the 12 months ending March 2019.

This is an 80% increase from the low-point in the year ending March 2014, when there were 23,945 offences, and is the highest number since comparable data was compiled.

These statistics do not include those from Greater Manchester Police because of data recording issues.

Out of the 44 police forces, 43 recorded a rise in knife crime since 2011.

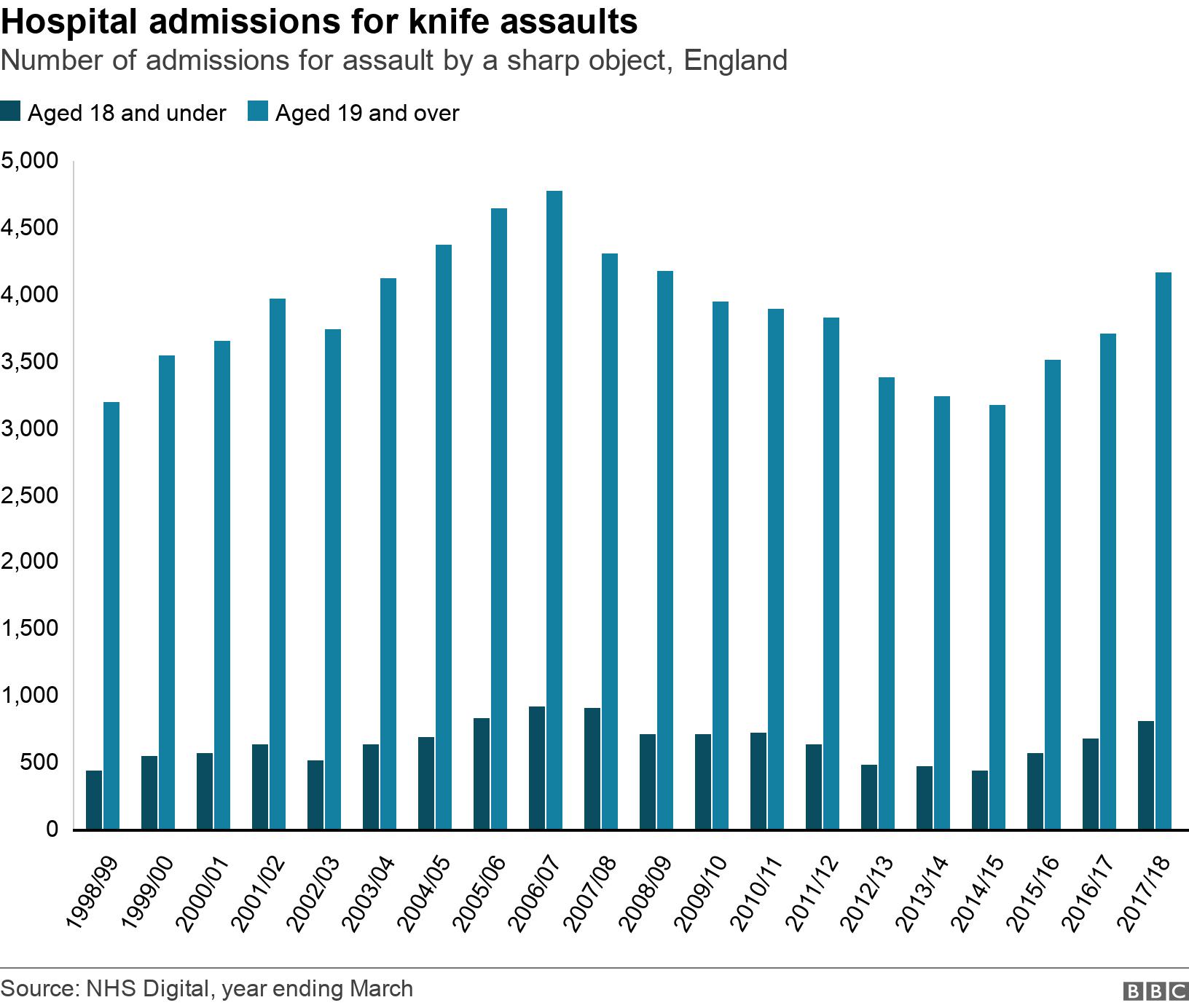

Police figures are prone to changes in counting rules and methods, but data for NHS hospitals in England over a similar period showed an 8% increase in admissions for assault by a sharp object, leading the Office for National Statistics (ONS) to conclude there had been a "real change" to the downward trend in knife crime.

Doctors said the injuries they were treating were becoming more severe and the victims were getting younger, with increasing numbers of girls involved.

All of the statistics here relate to England and Wales. Policing, criminal justice and sentencing are devolved in Scotland and Northern Ireland, which also collect crime data in slightly different ways.

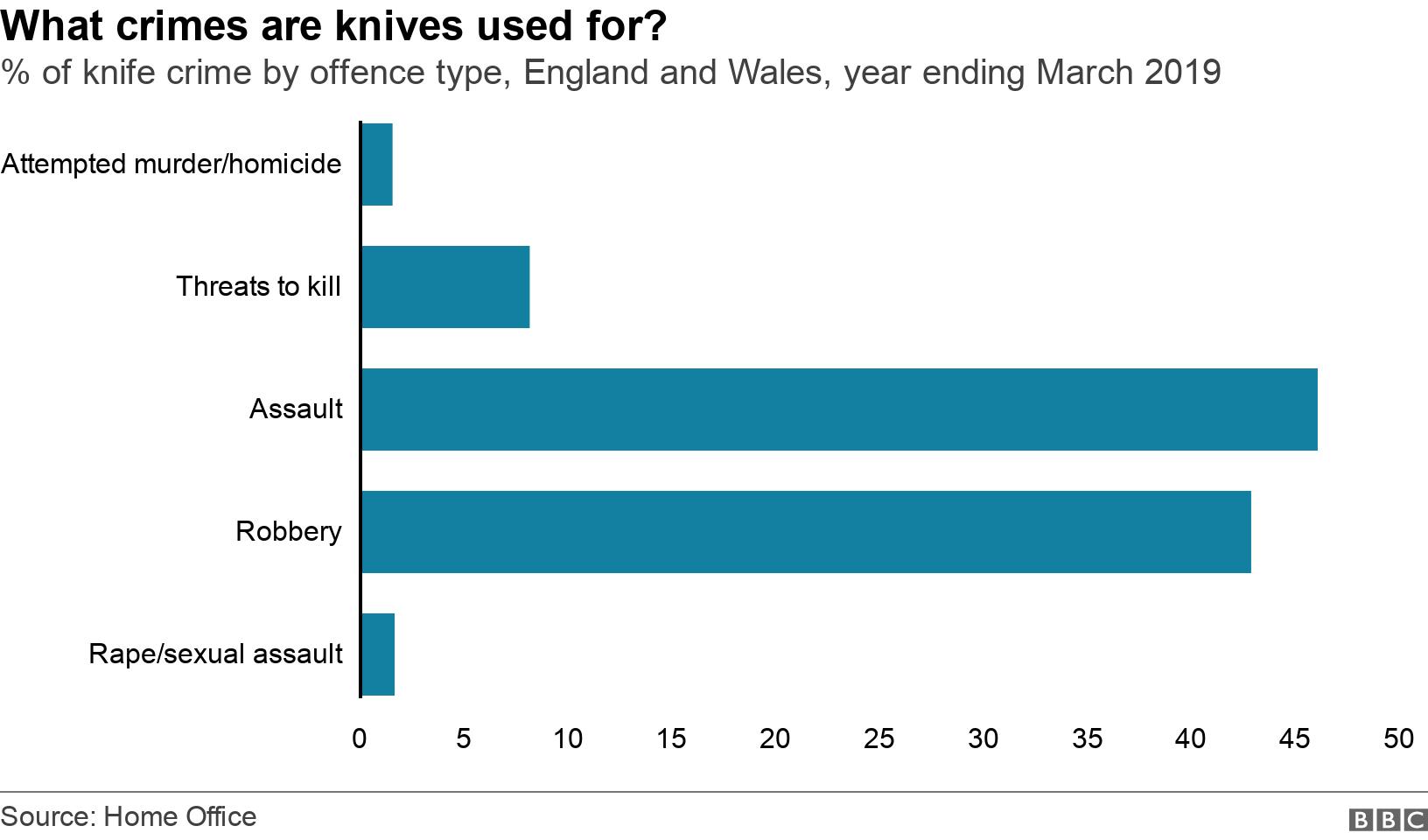

In the latest figures, which include only selected knife offences, about half, 21,700, were assaults that caused an injury or where there was an intent to cause serious harm; a further 20,172 involved robberies.

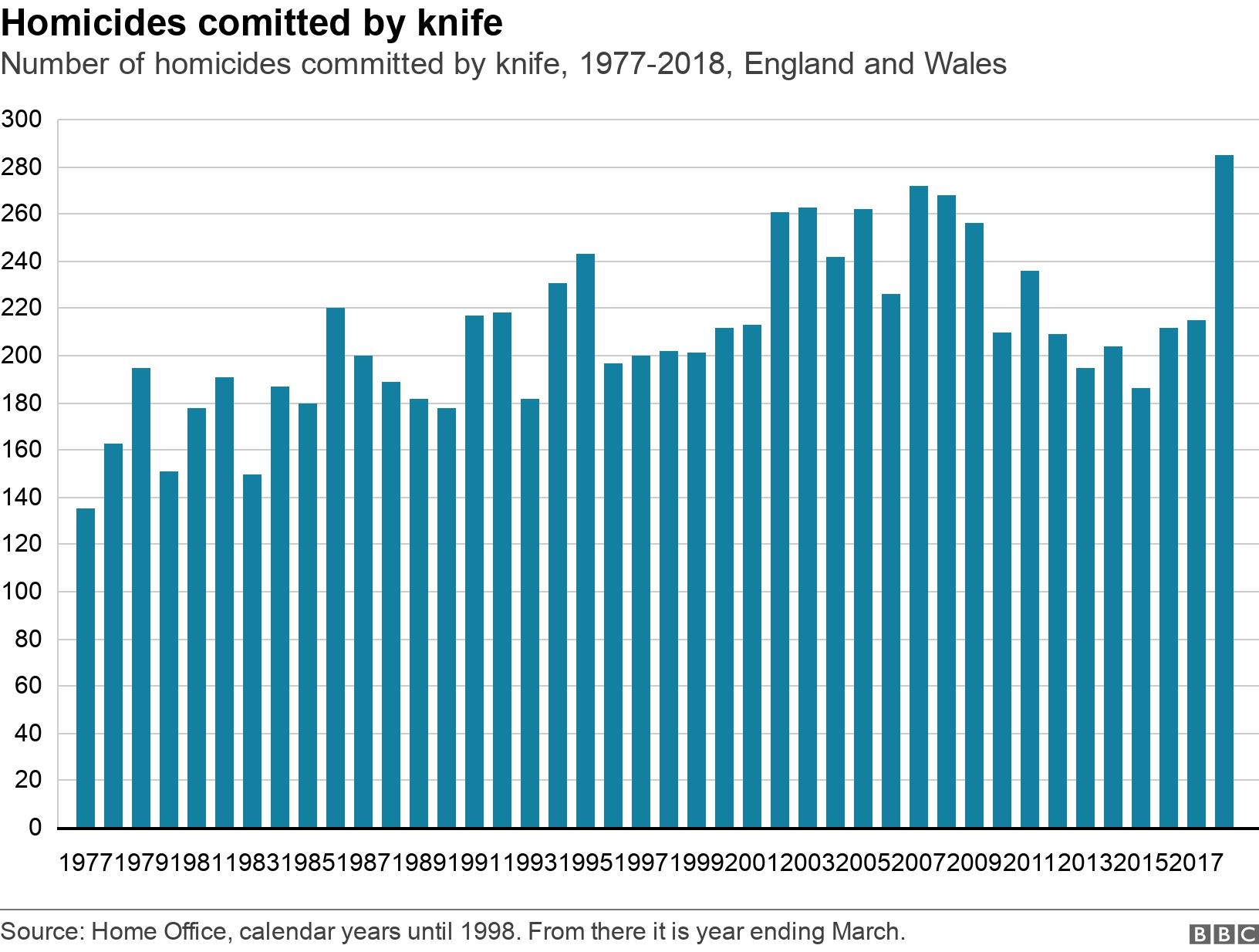

These figures focus on homicides, or killings, a category comprising cases of murder, manslaughter and infanticide. In about two out of every five killings, the victim was fatally assaulted with a sharp object or stabbed to death.

The number of knife-related homicides went from 272 in 2007 to 186 in 2015. Since then it's risen every year, with a steep increase in 2017-18, when there were 285 killings, the highest figure since 1946.

One in four victims were men aged 18-24.

The figures also show 25% of victims were black - the highest proportion since data was first collected in 1997.

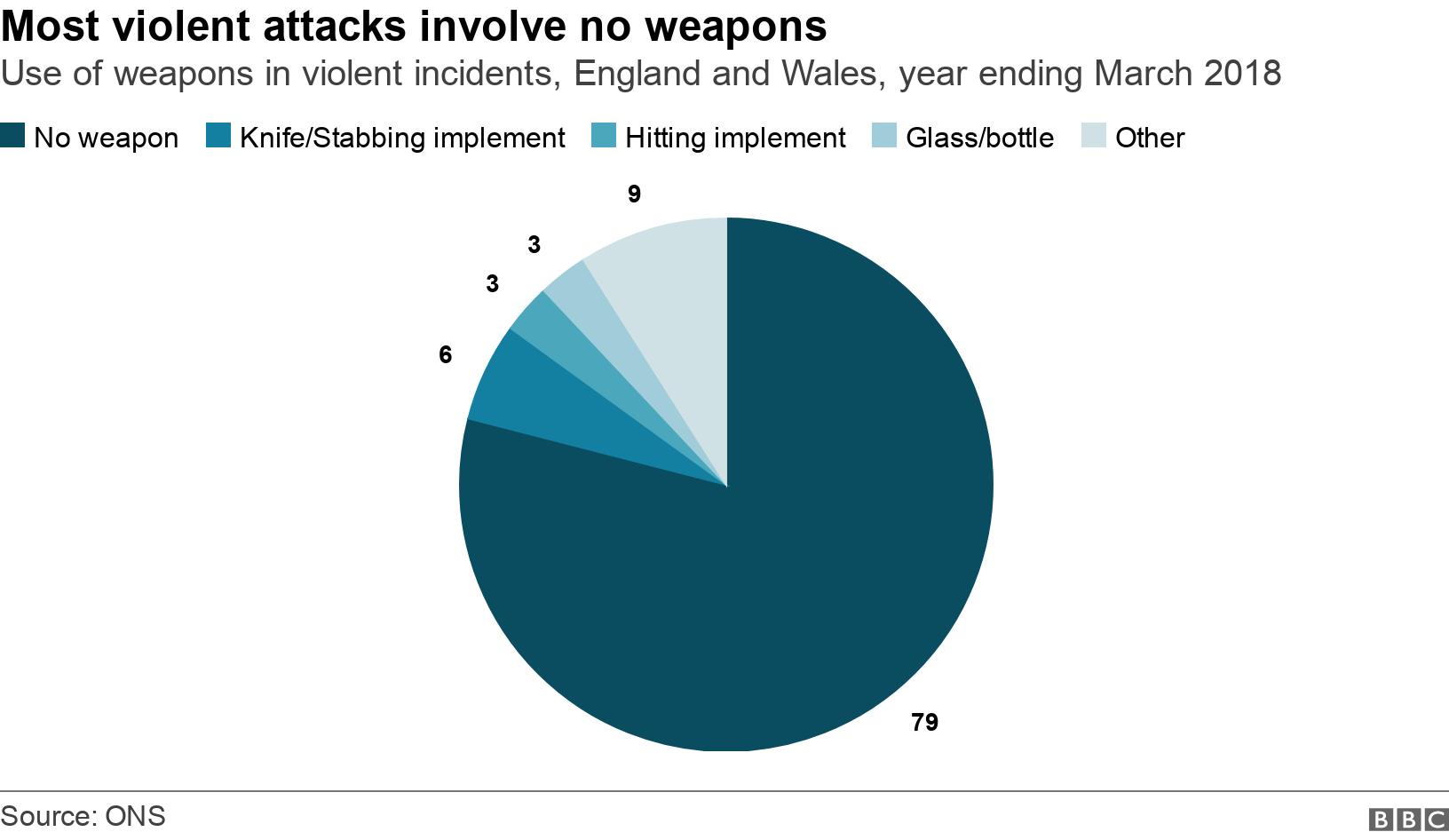

Although knife crime is on the increase, it should be seen in context. It's relatively unusual for a violent incident to involve a knife, and rarer still for someone to need hospital treatment.

Most violence is caused by people hitting, kicking, shoving or slapping someone, sometimes during a fight and often when they're drunk; the police figures on violence also include crimes of harassment and stalking.

The Crime Survey for England and Wales, which includes offences that aren't reported to police, indicates that overall levels of violence have fallen by about a quarter since 2013.

However, the police-recorded statistics - which tend to pick up more "high harm" crimes - have indicated that the most serious violent crime is increasing.

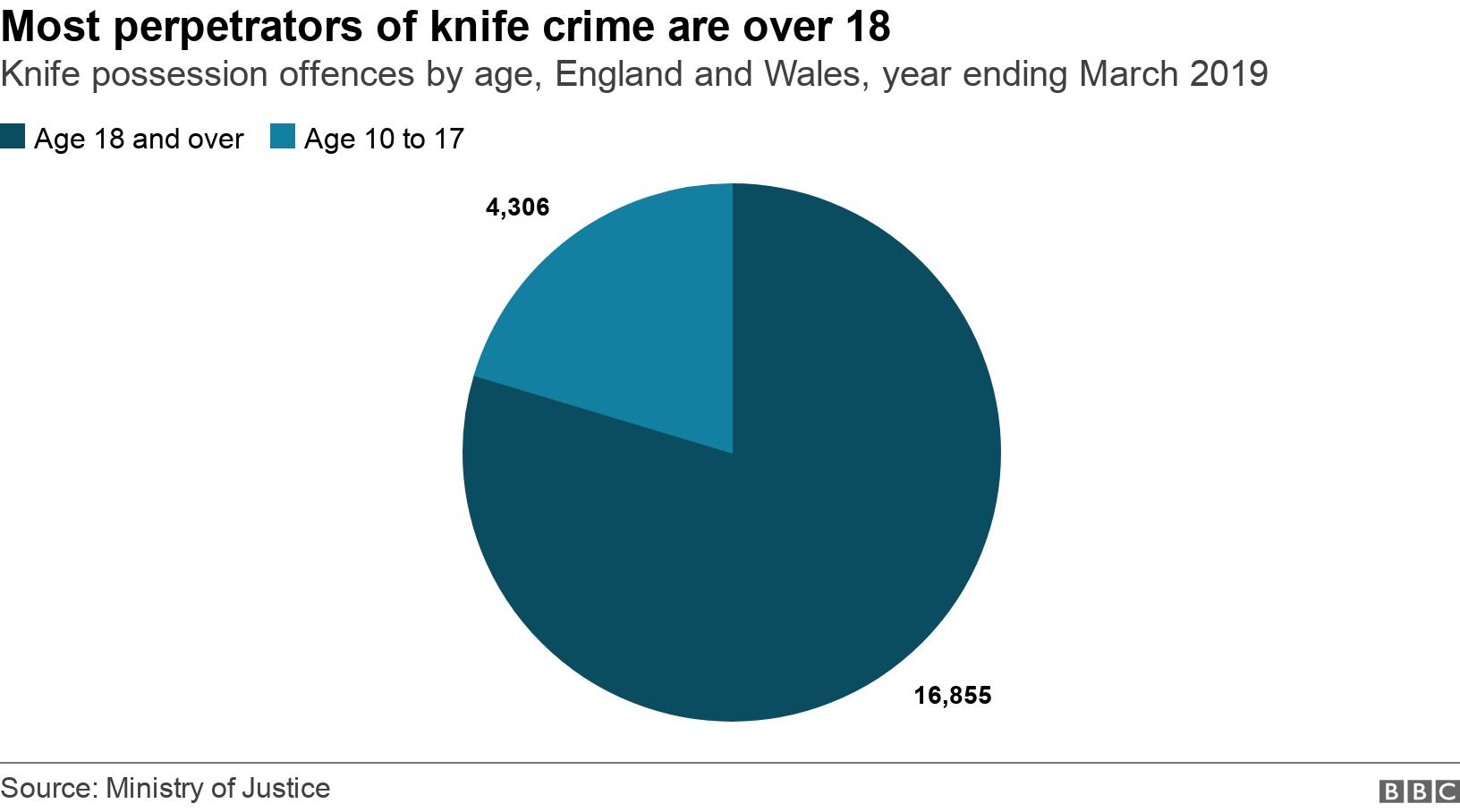

In the year to March 2019, 22,041 people were cautioned, reprimanded or convicted for carrying a knife in England and Wales, most of whom were adults. But one in five - 4,451 - was under the age of 18.

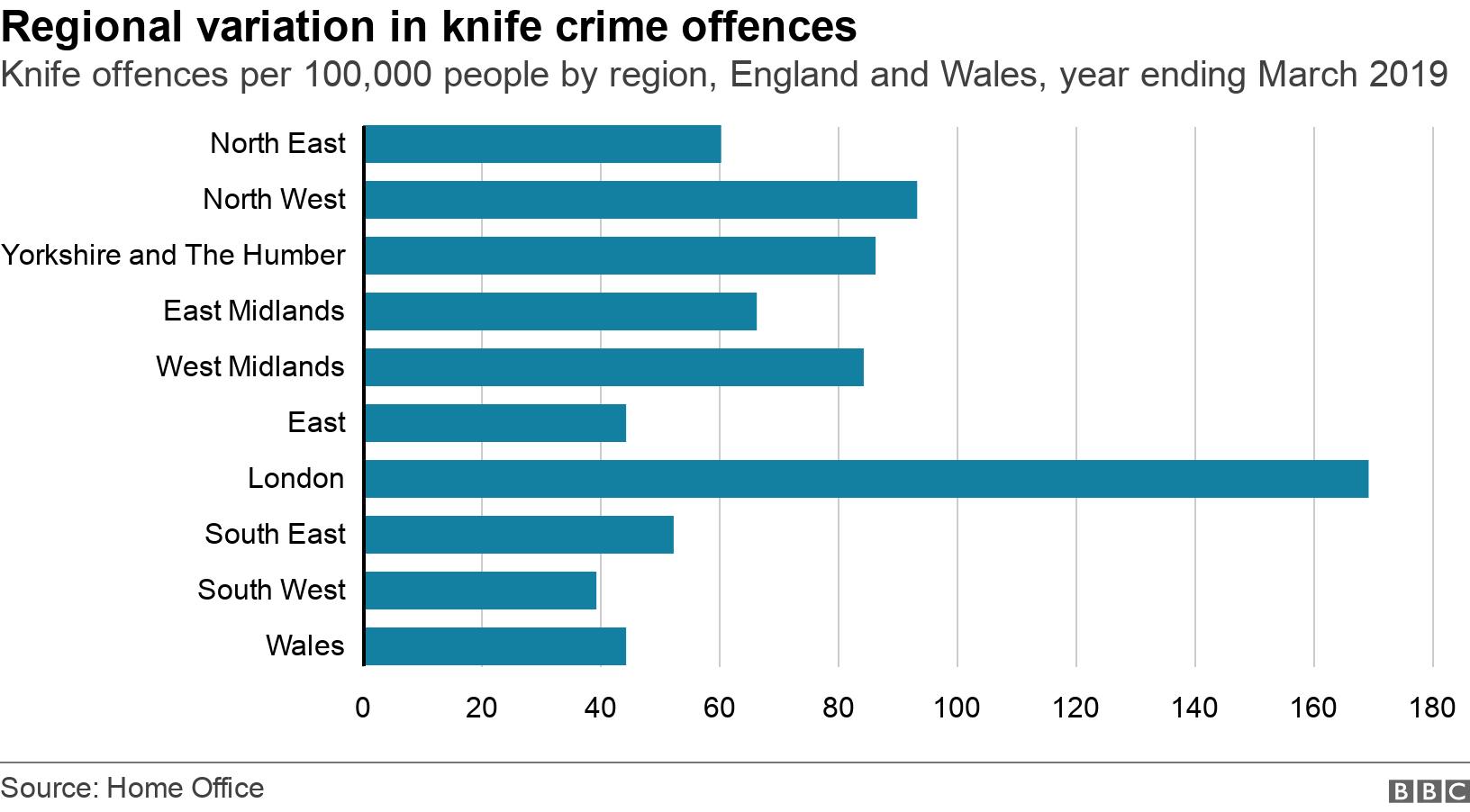

Knife crime tends to be more prevalent in large cities, particularly in London.

For every 100,000 people in the capital, there were 169 knife offences in 2018-19.

In 2018, figures from the mayor's office showed that young black and minority ethnic teenage boys and men were disproportionately affected, as both victims and perpetrators.

The Metropolitan Police Chief Commissioner Cressida Dick has said tackling violence in London is her "priority".

Next highest was the North West, with 93 knife offences per 100,000 population, and Yorkshire and the Humber, 86.

The explanations for rising knife crime have ranged from police budget cuts, to gang violence and disputes between drug dealers.

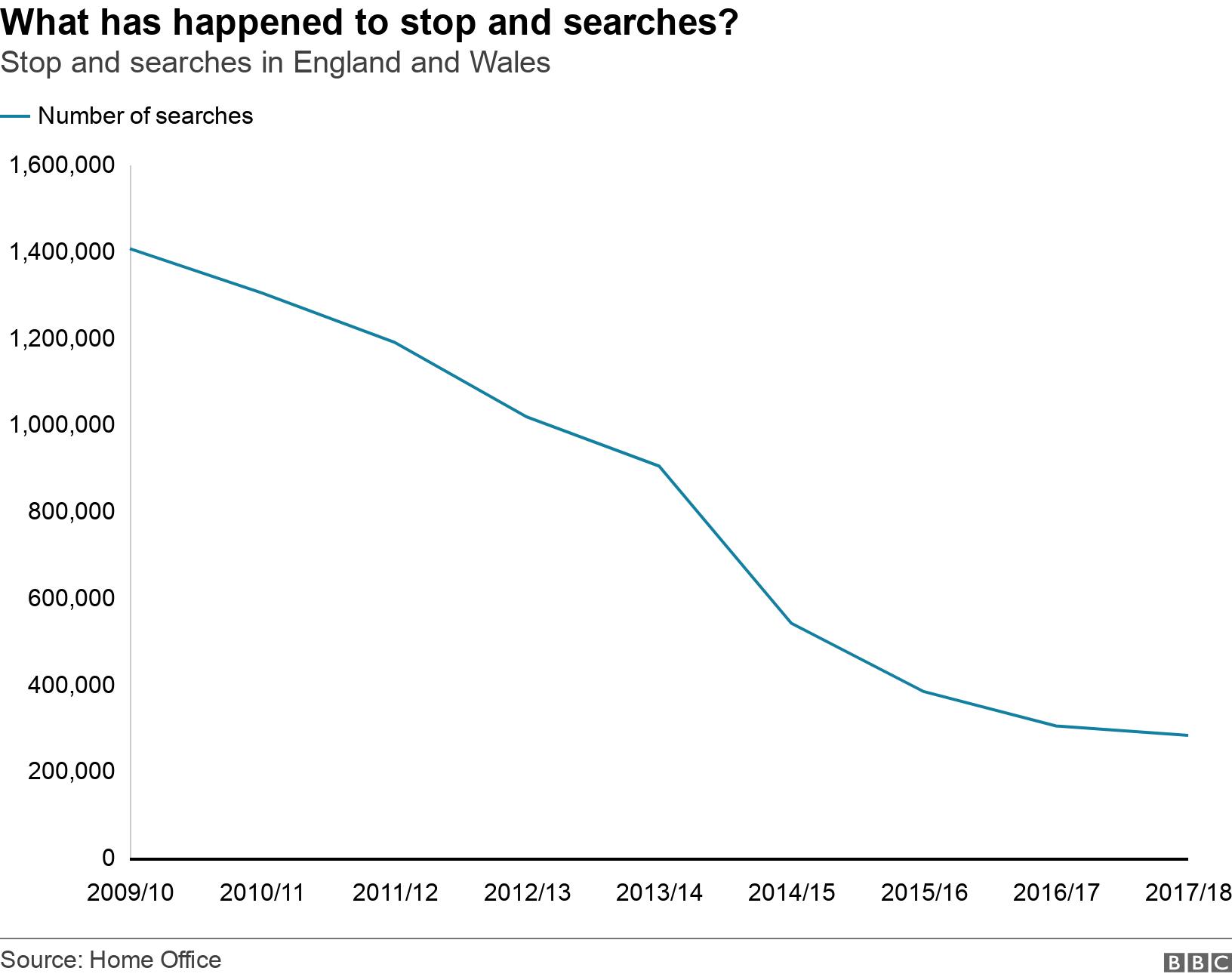

Some have also cited the steep decline in the use by police of stop and search.

The powers enable officers to search people on the street if they have reasonable grounds to suspect they may be carrying weapons, illegal drugs, stolen property or items to be used to commit a crime. People can also be searched without reasonable grounds if a senior officer believes there's a risk of serious violence in a particular area.

From 2009, the number of stops fell sharply across England and Wales, especially in London, primarily because of concerns that the measures unfairly targeted young black men, wasted police resources and were ineffective at catching criminals.

Theresa May, as home secretary, led efforts to drive down the number of stops, but there's anecdotal evidence from police that young people are now more inclined to carry knives because of growing confidence they won't be stopped.

The statistical basis for that is far from clear - but Scotland Yard, with the mayor of London's support, has begun increasing the use of stop and search again.

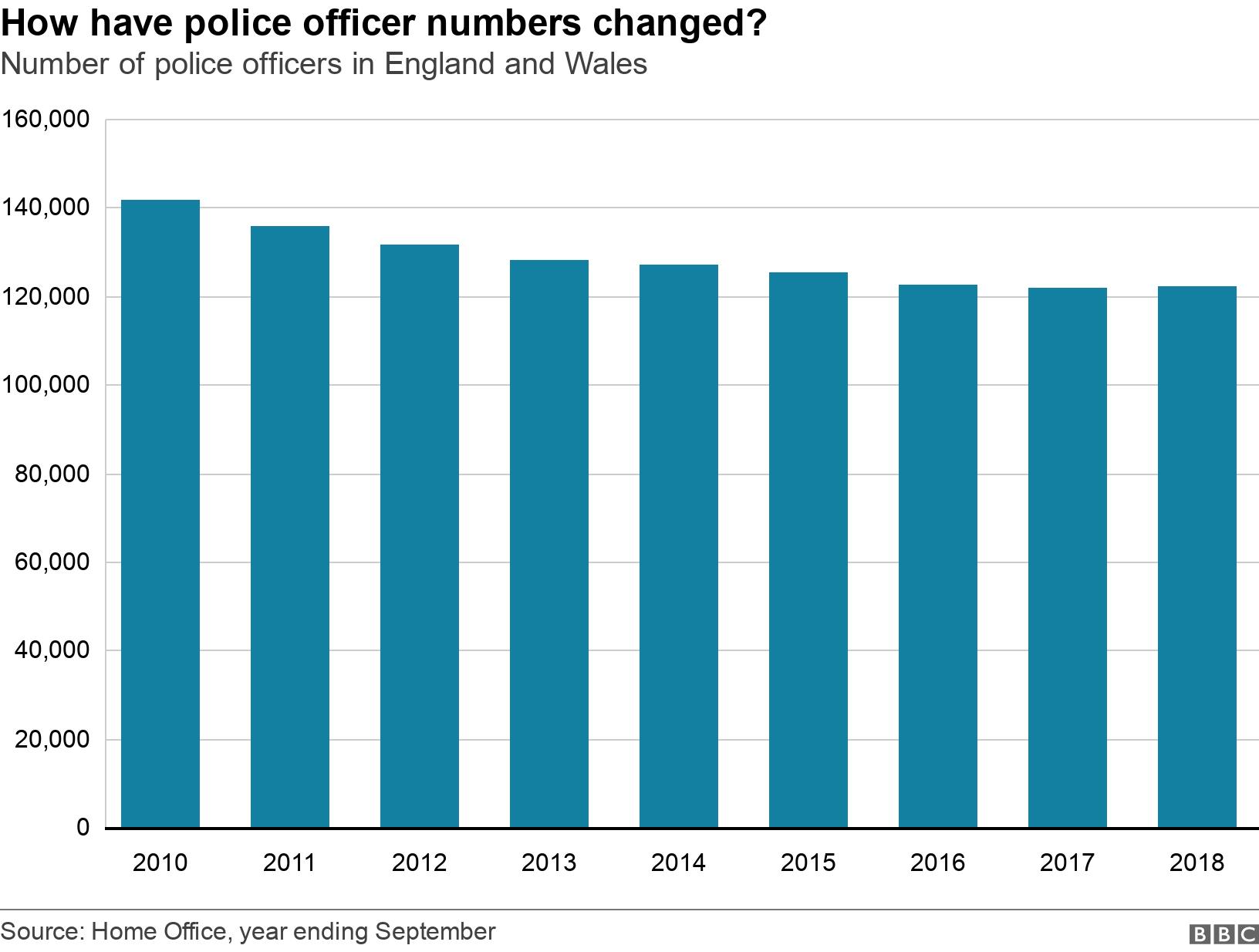

Since 2010, police numbers have decreased by almost 20,000.

Prime Minister Theresa May has said there is no "direct correlation" between the rise in knife crime and a fall in police numbers, but the issue is contested.

In 2018, a Home Affairs Committee report said police forces were "struggling to cope" amid falling staff numbers and a leaked Home Office document said they had "likely contributed" to a rise in serious violent crime.

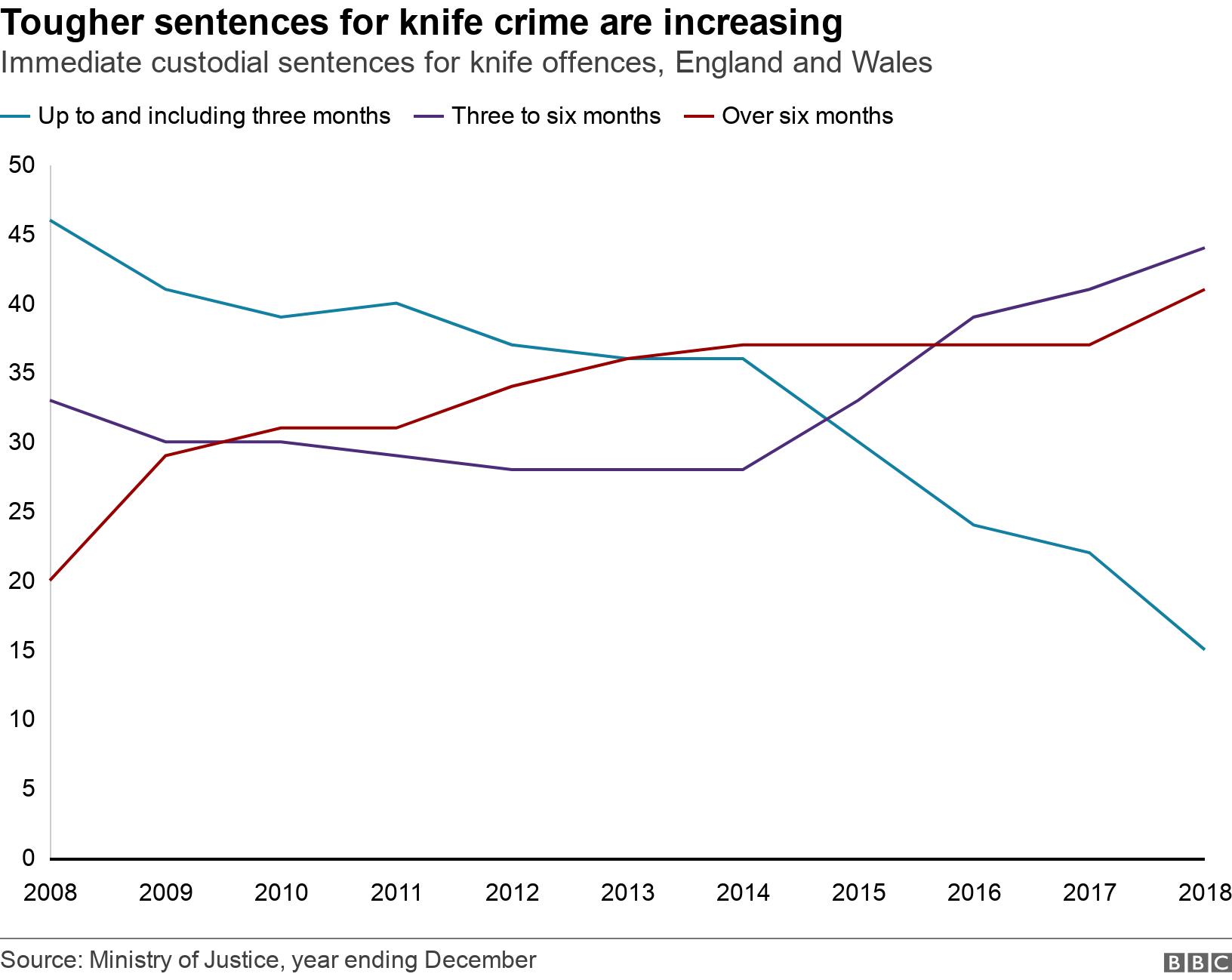

The average prison term for those jailed for carrying a knife or other offensive weapon has gone up from almost five months to well over eight months, with 85% serving at least three months, compared with 53% only 10 years ago.

Sentences for all kinds of violent crime have been getting tougher, particularly for knife crime. The Ministry of Justice tracks the penalties imposed for those caught carrying knives and other offensive weapons in England and Wales.

In the year ending December 2018, 37% of those dealt with were jailed and a further 18% were given a suspended prison sentence. The figures for 2008, when the data was first compiled, were 20% and 9% respectively. Over the same period, there's been a steady decline in the use of community sentences, and a sharp drop in cautions, from 30% to 11%.

Public anxiety about knife crime, legislative changes and firmer guidance for judges and magistrates have led to the stiffer sentences, although offenders under 18 are still more likely to be cautioned than locked up.

Additional research by Ben Butcher.

This piece was originally published in January 2018, but is updated regularly to include the latest statistics.

- Published1 November 2017