How should we tackle the loneliness epidemic?

- Published

Cristiano Ronaldo has 120 million. Barack Obama has 53 million. Donald Trump has 24 million. I am - of course - talking about Facebook followers.

Is Donald concerned that Barack has twice as many cyber-mates as he does? Or does he take solace in the fact that Hillary Clinton only has 10 million?

But then, on this side of the pond, Jeremy Corbyn has 1.4 million. Theresa May can only manage 550,000 while Vince Cable has just 11,600.

Facebook followers are not proper friends, of course. They don't pop round for a coffee and a chat. If they did, Cristiano would have to cater for 330,000 chums every day. Which is a lot of instant and semi-skimmed.

We've never been so connected, but for millions, this is the age of loneliness.

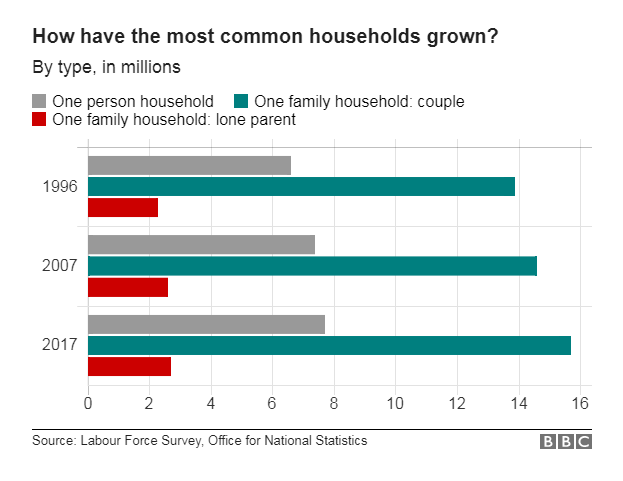

One of the biggest changes to the way we live has been the big increase in the number of people who live alone.

More than a quarter of all households in the UK contain just one person, around 7.7 million people, and this is predicted to increase by another two million over the next decade or so.

It is partly about living longer - older people whose partners have died increasingly find themselves on their own. Around 2.2 million people over 75 live alone, some 430,000 more than in 1996.

But it is also about lone parents on their own after their children have left home, and the newly single as a consequence of relationship breakdown - particularly middle-aged men.

Almost 2.5m people aged between 45 and 64 now live alone in the UK, almost a million more than two decades ago, the fastest rising age group.

You might also be interested in:

Now, for many people living on your own is not a problem. The International Journal of Ageing and Later Life recently included an article complaining about the Finnish media's portrayal of lonely older people as a problem.

One section, entitled The Possibility of Positive Loneliness, argued that solitude, silence and privacy can be seen as necessary requirements for creative work.

Furthermore, the paper suggested, positive loneliness is not merely a prerequisite for writing or painting, but it also has other beneficial meanings.

There are risks in muddling loneliness and being alone. Some people do like their own company and revel in the qualities of solitude. The American essayist Alice Koller determined to become a hermit, and from that experience wrote a series of essays called The Stations of Solitude.

"Being solitary is being alone well," she concluded. "Being alone, luxuriously immersed in doings of your own choice, aware of the fullness of your own presence rather than of the absence of others. Because solitude is an achievement."

I tend to be more persuaded by the thoughts of the philosopher Francis Bacon on the subject: "Whosoever is delighted in solitude is either a wild beast or a god."

It was interesting to note some of the UK press reaction a few years ago to a speech on social exclusion and isolation given by David Halpern, from what was then known as the Downing Street nudge unit.

The Behavioural Insights team, which is still going strong, was looking at how behavioural economics and psychology might be exploited to deal with loneliness.

Mortality risk

At a summit in Sweden, Mr Halpern was asked about how government might encourage older people to stay active.

He replied: "If you have got someone who loves you, someone you can talk to if you have got a problem, that is a more powerful predictor of whether you will be alive in 10 years' time, more than almost any other factor, certainly more than smoking."

He talked of the under-occupation of houses and the desirability of pensioners returning to work.

The response from some quarters was vitriolic. One newspaper headlined the story, Elderly told - go back to work and downsize, quoting the Saga over-50s group saying it was "outrageous social engineering for the government to suggest older people don't deserve to live in their own homes".

The libertarian blogger Anna Raccoon also interpreted the remarks as evidence of a meddling and aggressive government: "The workhouse beckons, work until you drop. Can't have you dying peacefully at home; die surrounded by your exhausted fellow pensioners."

In fact, the research David Halpern referred to is a meta-analysis of 148 studies into the effects of social isolation on mortality, external conducted by academics at Brigham Young University and the University of North Carolina.

The researchers were able to look at the lives of almost 309,000 people for an average of seven-and-a-half years - a seriously big sample.

What emerged was that those with stronger social relationships had a 50% increased likelihood of survival than those who lived more solitary lives. A seriously powerful finding.

The effect was consistent across a number of factors - age, gender, health status, follow-up period, and cause of death.

Social creatures

This research doesn't show that pensioners are better off having friends. It suggests that we are all likely to enjoy health benefits if we have busy social lives. Human beings are social creatures and starved of contact we can, quite literally, die.

The conclusion to the US research makes the point that "many decades ago, high mortality rates were observed among infants in custodial care [ie orphanages], even when controlling for pre-existing health conditions and medical treatment".

It was then noticed that lack of human contact predicted mortality. "The medical profession was stunned to learn that infants would die without social interaction," the research team recalled. "This single finding, so simplistic in hindsight, was responsible for changes in practice and policy that markedly decreased mortality rates in custodial care settings."

Loneliness is bad for our health. Seriously bad. Doctors have known this for decades.

An article in Science magazine in 1988 noted that "social relationships, or the relative lack thereof, constitute a major risk factor for health - rivalling the effect of well-established health risk factors such as cigarette smoking, blood pressure, blood lipids, obesity and physical activity".

The more recent research concludes that, if the impact of isolation is potentially so great on our health, we should do more to prevent it.

"Medical care could recommend if not outright promote enhanced social connections; hospitals and clinics could involve patient support networks in implementing and monitoring treatment regimens and compliance, etc."

Prof Jane Cummings, NHS England's chief nursing officer, has warned of the dangers of loneliness and cold weather

Prescriptions for a dose of friendship and a couple of tablets of company to be taken three times a day? Why not? But perhaps the findings should prompt us to go further.

What is really required, it seems to me, is for communities to function well. For neighbourhoods to take responsibility for their own.

Not just keeping an eye out to check the milk and the paper has been taken in, but to find ways of making newcomers feel welcome and long-termers feel part of something bigger than themselves, to feel confident that they can live their days, like Trappist monks if they wish, knowing that they are still plugged into a society which is ready to offer company and support if or when required.

Most people would agree that it is not the job of the state to tell people they have got to go to barn dances or whist drives. But it can make available information on the benefits of friendship and nudge communities into helping their members live fulfilled social lives when they want to.

'A great service to humankind'

Theresa May has spoken of her determination to reduce the loneliness that so many people say they feel. "More than nine million of us say that we always, or often, feel lonely," she told a Downing Street reception celebrating the work of the Jo Cox Loneliness Commission, set up by the family of the murdered MP.

Tracey Crouch said she was proud to lead cross-governmental work to tackle the "generational challenge" of loneliness

The prime minister has appointed a government lead on loneliness, Tracey Crouch, and promised that ministers "will do all that we can to see that, in [Jo Cox's] memory, we bring an end to the acceptance of loneliness in our society".

The commission has assembled survey evidence suggesting that 200,000 older people had not had a conversation with a friend or a relative in more than a month and up to 85% of young adults with disabilities say they feel lonely most days.

The world-renowned behavioural economist Prof Daniel Kahneman, told me this: "It turns out something like 15% of the overall time that people spend is bad time, unpleasant time. Now that gives you something to get your teeth into.

"If you manage to reduce that number from 15% to 14%, you would be doing a great service to humankind!"

What proportion of that 15% is unpleasant because people are on their own when they yearn for company?

Just imagine if the world could offer those people the hand of friendship. A smile and a word. Company when they want it and privacy when they don't. Now that would be a great service to humankind.

- Published7 February 2018

- Published1 February 2018

- Published31 January 2018

- Published17 January 2018

- Published14 December 2017

- Published22 September 2017