The death of the local newspaper?

- Published

Inside the Coventry Evening Telegraph's old printworks, frozen in time

The government has announced a review into the future of the newspaper industry, warning the closure of hundreds of regional papers is fuelling fake news and is "dangerous for democracy". But is it too late to save local newspapers?

There's a spot just off the M6 in Coventry where you can time-travel into the 1950s.

Walking through beech-panelled boardrooms and a butler's pantry you might not guess this was the Coventry Evening Telegraph for nearly half a century.

The rooms look abandoned mid-shift, as though the reporters have spiked their last story and walked out.

There's a baseball cap on one of the old PCs, and old family photos on the desks.

The building was boarded up in 2012 when the paper finally left for more modern premises.

It's due to be turned into a boutique hotel - just in time for Coventry's turn as the UK's new City of Culture in 2021.

Brushing dust from the huge but silent printing press Mick Williams, who started working at the Telegraph in 1972 aged just 16, says fondly: "This was my baby. Working here wasn't just a job, there was a prestige attached to it because you were bringing people their news. It's like a museum now."

This building was boarded up in 2012 when the paper moved to smaller, more modern offices

The old building is now a pop-up arts space where tourists come to take photos of the rooms filled with dead technology and dust.

Standing in the room where he worked for 30 years, ex-printer Mick reflects on the future of local papers.

"I suppose you can get the news from different parts of the media these days. I know I can look at Facebook local groups and I can get some news of what's happening that doesn't appear in the Telegraph until perhaps three days later. [But] you've lost a bit of community spirit haven't you? You've lost a connection."

The rooms are still as they were left six years ago

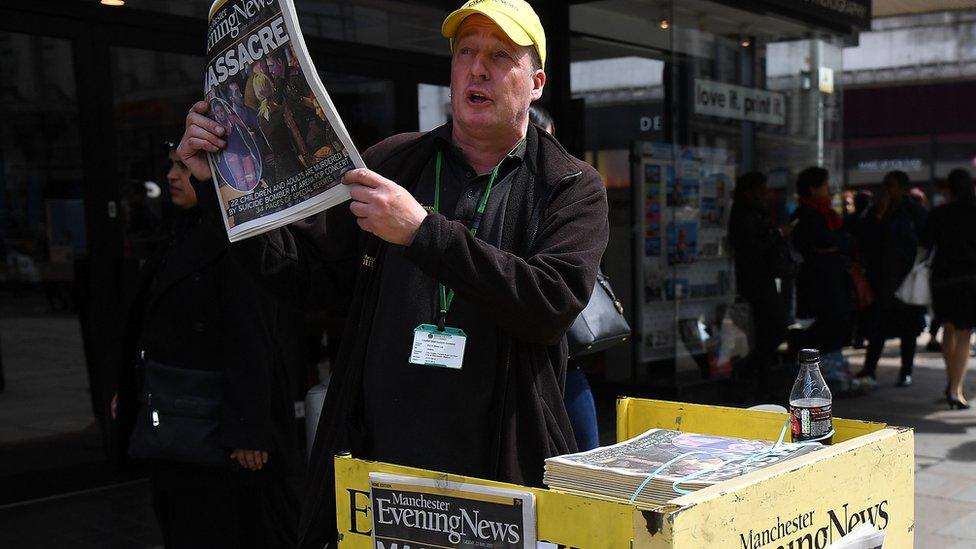

Earlier this month, when Prime Minister Theresa May launched a government review into the sustainability of the British press, she praised the work done by local journalists in covering the terror attack on the Manchester Arena, in which 22 people died.

The coverage, by the Manchester Evening News, was, she said, "a very good example of where good quality local journalism and a good quality local paper can actually be out there supporting their community".

In an act of solidarity following the bombing, 30 local journalists from Teesside to Dublin answered a call by MEN publisher, external Trinity Mirror to cover shifts for the exhausted reporters, photographers, subs and editors.

Then MEN editor Rob Irvine, whose We Stand Together campaign raised £2.5m for the families of victims, said at the time: "We will make Greater Manchester an even greater place. We will care about each other and support our neighbours. The terrorists will fail. We will prevail."

The Manchester Evening News was praised for its coverage of the terror attack

But the National Union of Journalists has warned that the regional newspaper industry is in "free-fall".

Since 2005 more than 200 local papers have closed in the UK and the number of regional journalists has halved to around 6,500, with staff cuts, centralised newsrooms, sub-editing and printers re-located miles from local communities, leaving press benches in councils and courtrooms increasingly empty.

An estimated 58% the country has no daily or regional title and rural areas are increasingly reliant on London-based media and their own social networks for local news.

Public 'losing a voice'

A 2016 study found UK towns, whose daily local newspapers had shut, suffered from a "democracy deficit" with reduced community engagement and increased distrust of public bodies.

"We can all have our own social media account, but when [local papers] are depleted or in some cases simply don't exist, people lose a communal voice. They feel angry, not listened to and more likely to believe malicious rumour," said Dr Martin Moore, director of the Centre for the Study of Media, Communication and Power at King's College London, which published the report, external.

"Because it's not necessarily the sexy stuff - like big investigations - for quite some time people didn't notice it was disappearing."

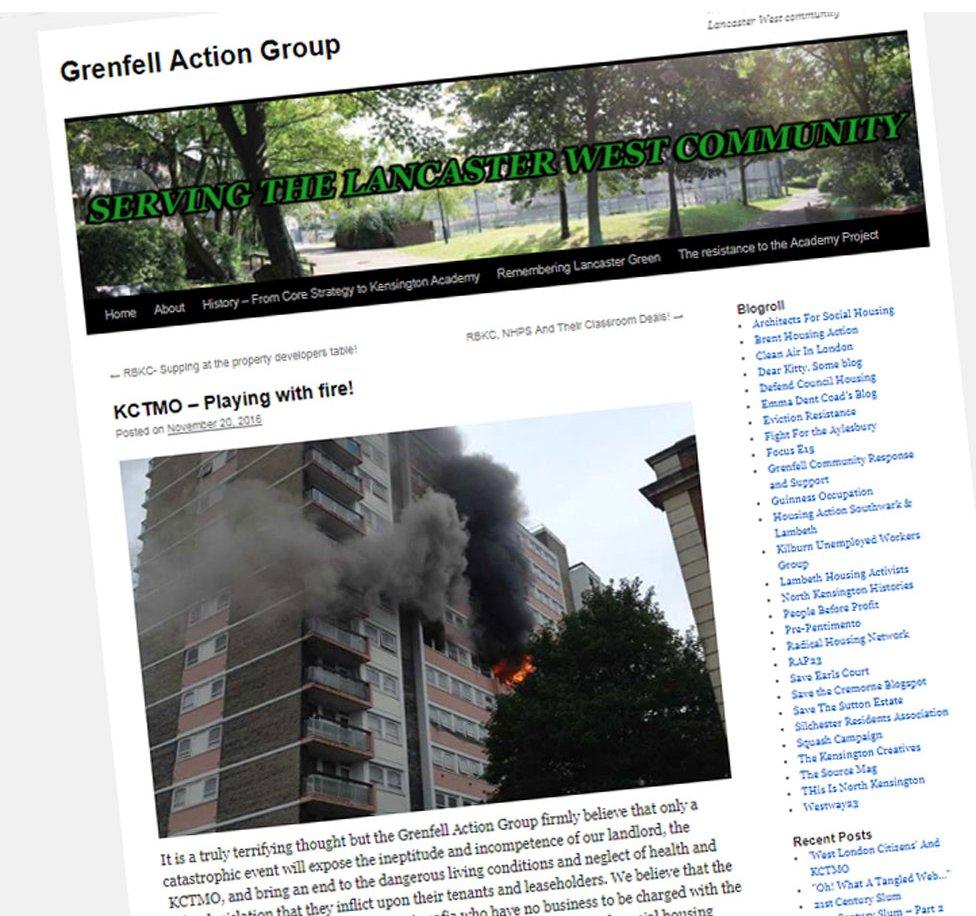

A blog foresaw the Grenfell Tower fire, but no journalists were there to follow it up

Dr Moore says the "repercussions of a lack of a local press" were seen after the Grenfell Tower fire, which killed 71 people in June last year.

The nearest local newspaper - The Kensington and Chelsea Chronicle - closed in 2014. After that, the area was covered by a single journalist working out of a hub newsroom based in Surrey.

"If there had been reporters consistently on the ground who could elevate residents' voices then it's hard to think that the authorities wouldn't have reacted in some way more constructively than they did. As a consequence they went unheard," Dr Moore says.

The paper blamed the error on "a technical problem"

In December the city of Cambridge woke to find that its 130-year-old daily paper The Cambridge News had printed 12,000 copies missing the front-page headline.

Readers were quick to poke fun at the paper on social media with the editor-in-chief blaming "a technical problem".

But former deputy editor Paul Kirkley said behind the laughter the incident highlighted that "management have cut resources to the bone and then kept on cutting".

The paper had changed publishers three times in five years including Local World, which made a large number of staff redundant, Trinity Mirror which removed 10 years of stories from the website and Iliffe News and Media, which was successfully taken to court by HMRC for using an alleged tax-avoidance scheme to ring-fence £51.4m in income.

The Yattendon Group, which formerly owned Iliffe News and Media, declined to comment.

Current publisher Trinity Mirror said: "Regarding the removal of story archives, it is wrong to use the word 'deleted'. They still exist and can be accessed by our reporters. Given that less than 1% of readers read content more than four months old, we feel resources are better placed covering breaking local news for our readers."

The NUJ says Newsquest doesn't value the professional skills of their Swindon journalists

Last month journalists at The Swindon Advertiser went on strike over alleged "poverty pay" and job cuts at the title. owned by Newsquest, given the hashtag #scroogequest on Twitter.

But Newsquest chief executive Henry Faure Walker, says although digital income was rising, cuts were needed partly because the papers' traditional funding model of advertising had declined so badly and social media giants like Facebook and Google were "free-riding" newspaper's content and giving "peanuts in return."

He welcomed the government review. "The important point is that if a publisher doesn't adapt their business to the new economic reality, then they will close and the town or city will lose their newspaper."

In 2016 the newspaper trade body The News Media Association (NMA) also raised concerns about the rise of digital news saying the BBC's news website "risks damaging the local press sector, which is currently in transition to a sustainable digital world".

Last year, in response, the corporation and NMA, launched the Local News Partnership Scheme. It set up a shared data unit where local reporters can learn new skills, access BBC News video and audio material and local papers can use 150 licence-fee funded reporters to cover public meetings as part of its £8m annual Local Democracy Scheme.

But the chair of the independent press regulator Impress, Jonathan Heawood, said it was not just the big publishers that new funding models should be aimed at.

Megan Lucero (centre) runs a new project called the Bureau Local, using data to uncover local stories

"There are around 400 innovative and commercially successful, independent publishers in operation already like The Ferret in Scotland or The Bristol Cable which are co-operatives.

"I think this could be the rebirth of the local newspaper if we work out how to help the new business models thrive in the long run, not prop up the old ones."

The Bureau Local, a branch of the Bureau of Investigative Journalism, is another model looking to improve the future of local journalism.

Launched last year with a £500,000 Google grant, its aim is to support public-interest journalism by publishing free data online and collaborating with local and national papers and communities.

So far it is active in 106 UK cities and has helped publish more than 150 local stories - including an investigation into swing seats during the snap election, and council cuts to domestic violence services.

Bureau local director Megan Lucero said: "People are innovating the way they tell stories, we are innovating the way we consume it.

"It rests on how we see journalism- do we see it as a service or do we think it needs to thrive alone as a business? That is a decision we have to make as a society."

Correction: An earlier version of this article incorrectly stated that the Manchester Evening News had announced redundancies a month after the Manchester Arena Bombing of May 2017. The redundancies were announced in June 2016 and this line has been amended.

A complaint about the inaccuracy was upheld by the BBC's Executive Complaints Unit.

Death of the Local Newspaper? was broadcast on Radio 4's PM programme on February 19.

Alice Hutton worked for The Cambridge News between 2010 and 2012 when it was owned by Iliffe News and Media.

- Published24 November 2017

- Published6 December 2017

- Published6 February 2018