Russian spy: What now for the UK/Russia relationship?

- Published

A video still shows Sergei Skripal being detained by Russian security services in 2004

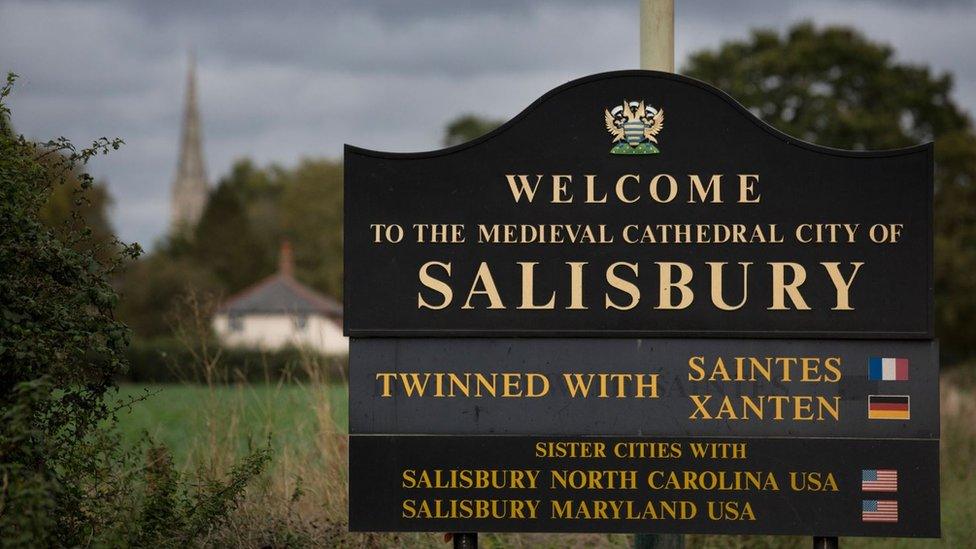

Britain's relations with Russia are already cool. The attempted murder of a former Russian spy in Salisbury could plunge that relationship even deeper into the diplomatic permafrost.

Before the basic facts of the case have been established, both sides have indulged in an early exchange of fire.

The Foreign Secretary, Boris Johnson, told the House of Commons there were echoes of the death of Alexander Litvinenko, another former Russian spy whose murder on British soil has been blamed on the Kremlin.

"It is clear that Russia is, I am afraid, in many respects now a malign and disruptive force," Mr Johnson told MPs. The country was, he said, launching cyber-attacks against British infrastructure which "I increasingly think that we have to categorise.. as acts of war".

In response, Maria Zakharova, Russia's foreign ministry spokeswoman, accused British politicians and journalists of using the incident to foster anti-Russian sentiment. "This story was straight away used to boost an anti-Russian campaign in the media," she said.

"It is difficult to see anything other than provocations aimed at harming the relations between our two countries." And of Mr Johnson, she said: "How can a man charged with foreign affairs, who has no relation to security organs, make such statements?"

Russian spy 'attacked with nerve agent'

Russian spy: What we know so far

Sergei Skripal and the 14 deaths under scrutiny

But does this matter? The relationship between London and Moscow could already be characterised as one of steady confrontation. It is certainly more strained than Russia's relations with other mainstream European countries such as Germany or France.

Britain strongly opposed Russia's annexation of Crimea and intervention in Ukraine and it backed tough UN and EU sanctions on Russia's economy as a result.

Britain also strongly opposed Russia's military support for President Assad's government in Syria that has led to the deaths of thousands of civilians. Britain has voiced its concern about Russia's alleged interference in the elections of western democracies, and what it sees as a threat to the international world order. And Britain is increasingly worried by the cyber-attacks on UK infrastructure emanating from Russian soil.

But if it emerges that the Russian state had any involvement in the poisoning of Sergei Skripal and his daughter, then the British government would find it hard to resist taking action that would strain relations further. In such circumstances, Boris Johnson has promised "appropriate and robust action".

Alexander Litvinenko lies in a hospital bed in London, shortly before his death in 2006

So what could that be? Well, the UK could expel some Russian diplomats, as it did after the former Russian spy Alexander Litvinenko was poisoned in London in 2006. But that has rarely changed Russia's behaviour.

It could impose unilateral sanctions on Russian individuals and businesses. But it is unlikely to get support from European partners for tougher EU-wide sanctions. Brexit makes those kinds of negotiations harder and some EU countries are already trying to soften their approach to Moscow.

The UK could make it more difficult for Russians generally to get visas to the UK. This certainly hurts. But it could be self-wounding as such restrictions might also hit Russian dissidents whom the UK welcomes and wealthy businessmen whose laundered cash the UK tolerates to support London's property market. Few analysts believe targeting rich Russians with tougher asset-stripping orders would make much difference. They would just take their money elsewhere.

The government could change the law, as some MPs want, to make it easier to target sanctions at Russians who violate human rights. But this would probably affect only a handful of people. And, as Boris Johnson has hinted, the UK could decide that members of the royal family and other dignitaries should not attend the football World Cup in Russia this summer.

Nuclear deal

The risk with any of these options is the scale of any Russian retaliation. British pension funds might get nervous if they have large investments in firms that are over-exposed in Russia. London estate agents might worry about the impact on the housing market if Russian money departed the capital.

And Britain would be reluctant to strain diplomatic relations too much. Despite all the hostility, the UK needs to talk to Russia about rebuilding Syria if and when the conflict ends. It needs to talk to Russia about deterring North Korea from producing nuclear weapons. And it needs to talk to Russia about protecting the Iran nuclear deal.

The UK could, of course, outsource these issues to other countries: they are all discussed on a multilateral basis. But to do so would run counter to the government's commitment to what it calls "a global Britain" foreign policy

So for all the huffing and puffing from the Commons and the Kremlin, it is perhaps more likely that any substantial response from the UK would be measured and long term and dependent on a clear outcome to the investigation into what exactly happened in Salisbury. And that might take some time.

- Published7 March 2018

- Published8 October 2018

- Published6 March 2018

- Published7 March 2018