NHS pay: What about the rest of the public sector?

- Published

More than a million NHS staff in England are set to get a pay rise, after seven years of having their wages frozen then capped at 1% as part of the government's austerity programme.

This was effectively a cut since their pay was not keeping up with the rising costs of living.

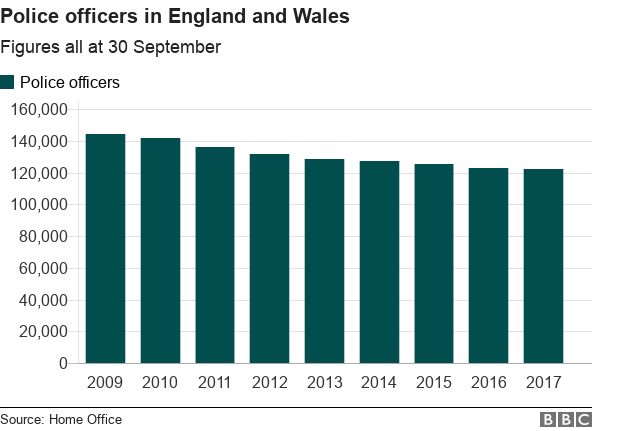

But it's not just workers in the health service who've had their pay restricted. Teachers, police officers, prison staff, firefighters and armed forces personnel have all had real-terms cuts to their wages.

So does this NHS offer spell the end of the cap on all public-sector workers' pay?

Police and prison officers

Firefighters, police and prison officers have already been offered pay rises in breach of the cap - although the firefighters union has rejected their pay offer.

Police and prison officers on the other hand have accepted rises of 1% with a 1% bonus, and 1.7%, respectively for the coming year.

There are two big differences from the NHS offer though.

First, the pay rises for NHS staff will be funded through extra money provided by the Treasury. But the police and prison officers' wage boost will have to be funded from the existing budget, so sacrifices may have to be made in other areas of spending on the services.

Secondly, NHS staff are getting an average of 6.5% over three years. But half of nurses will receive more than that, and the lowest paid NHS staff will receive pay rises of as much as 29%. So, many NHS staff's pay will keep pace with the rising cost of living for the first time in seven years.

That's not the case for police and prison officers.

Both of their pay offers are below the 2.4% inflation rate forecast by the Office for Budget Responsibility for 2018.

Prison officers were permanently banned from striking last year

Prison Officers Association general secretary Steve Gillan said at the time: "I have made it clear that it is a pay cut. It is not acceptable."

The Police Federation of England and Wales had asked for a 2.8% increase to basic pay. The Prison Officers Association had called for a 5% increase.

Firefighters

In July, firefighters were offered a 2% basic pay increase from last July, with a potential further 3% increase in line for this April.

But this was rejected by their union.

Fire Brigades Union general secretary Mark Wrack said in July: "This offer demonstrates that the 1% cap is dead in the water - but the offer from our employers is simply not enough."

Soldiers and teachers

Both teachers and military personnel are waiting to hear what their pay offer will be for the coming year.

The armed forces are expecting a report making recommendations on their pay imminently.

On 15 January, Defence Minister Tobias Ellwood told Parliament the armed forces had been "liberated from the 1% pay freeze".

But a letter from Defence Secretary Gavin Williamson said there was still a "need for pay discipline".

The then Education Secretary, Justine Greening, wrote to the teachers' pay review body in December, asking it to consider the need to address staff shortages when making its recommendations.

In the last review, some of the lowest paid teaching staff received a 2% pay increase - but most were kept at 1%.

So it looks like employers have now been given more freedom by government to offer their workers bigger pay rises the next time pay levels are set.

But if these increases aren't going to be funded by the Treasury and already financially squeezed services will have to fund them from their existing budgets, the question is will they?

The examples of police, prison and fire-service staff suggest employers are ready to inch past the 1% cap but are not yet offering pay rises that will mean their employees have more money in their pockets once inflation is taken into account.

What's the problem?

As well as the consequences for individuals of having their wages restricted, unions have pointed to problems with recruiting public-sector workers as an argument for lifting the cap.

Across most of the public sector, there have been problems with recruitment and retention of staff since 2010, although this varies across different professions.

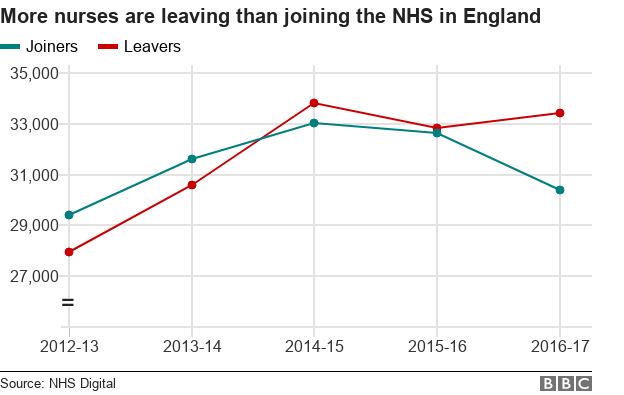

Almost 10% of all nurses now leave the NHS each year (33,000 last year). And leavers are outnumbering joiners.

Among teachers, the proportion of the workforce leaving each year is even higher.

However, it's difficult to attribute this to one thing.

The last time the NHS pay review body reported, in 2017, the report's authors said: "There continues to be little evidence that pay restraint in and of itself has, so far, caused serious widespread recruitment and retention issues."

But, they added, there were staff shortages in certain roles and geographical areas that may be due in part to pay, as well as issues such as workload.