The unspoken alcohol problem among UK Punjabis

- Published

For many British Punjabis, alcohol abuse is an open secret. Alcohol consumption is glamorised across different aspects of Punjabi culture and shame stops many seeking the help that they need.

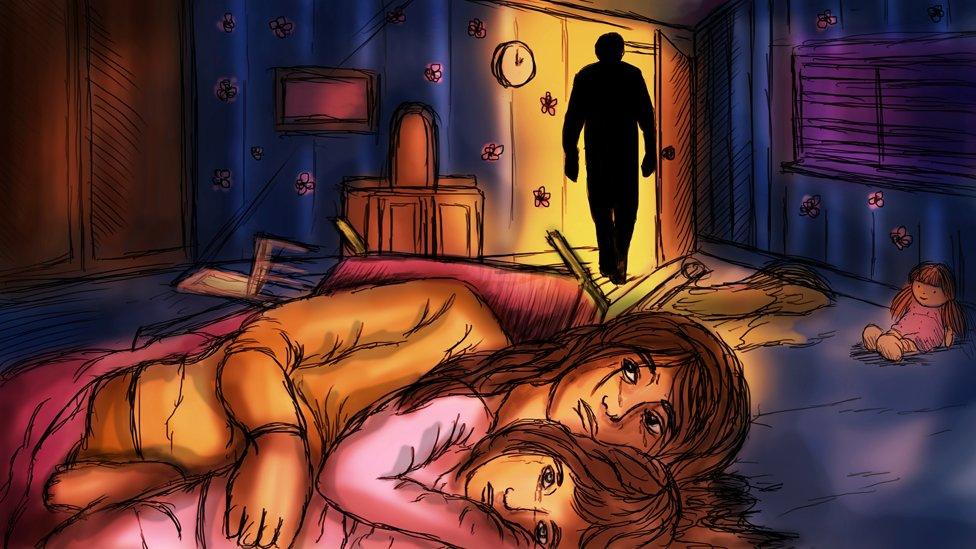

Harjinder read her daughter Jaspreet one last bedtime story, then kissed her goodnight. She was exhausted after a long day, and drifted off next to her daughter. Her toddler son was already asleep in the next room.

The next thing she remembers is her husband yelling. He was drunk and furious that when he returned from the pub she wasn't in their marital bed. In a rage, he flipped the child's bed throwing his wife and daughter to the floor. Harjinder hit the radiator hard with Jaspreet landing on top of her.

Incidents like this were a regular feature of Jaspreet and her brother Hardeep's childhood. "It was heartbreaking," Jaspreet says.

So when Harjinder found Hardeep, now aged 16, drinking whisky in his room after an argument with his alcoholic dad, she was terrified that he was following in his father's footsteps.

There are around 430,000 Sikhs in the UK, making up a significant proportion of the British Punjabi population. Harjinder herself is Sikh and amongst her community her experience isn't unique.

A new survey, commissioned by the BBC to investigate attitudes to alcohol among British Sikhs, found that - although drinking alcohol is forbidden in Sikhism - 27% of British Sikhs report having someone in their family with an alcohol problem. It's a problem which is rarely talked about openly in the community.

More than 1,000 British Sikhs responded to the survey - find out more using this interactive tool:

Harjinder moved in with her husband's family after their arranged marriage - both common practices within Punjabi and wider South Asian communities. She was shocked to find out how much her newly acquired family's social life centred around the men's excessive drinking.

The family, along with young children, would go to a friend's house and would stay there until two or three o'clock in the morning waiting for the men, and she started to feel increasingly isolated.

Rav Sekhon, a British Punjabi psychotherapist who works with ethnic minority communities, says: "There is really strong pride and honour for the family name. They don't want anyone to perceive them as having something wrong with them or any form of weakness."

You might also like:

Sanjay Bhandari is from a Hindu Punjabi family, a partner at a multinational city firm in London and a recovering alcoholic. After his father died when he was 15, he says he started drinking and never really stopped.

By his mid 30s, he realised that he hadn't been a single day without a drink for over seven years, and he'd been dependent on alcohol for much longer. He says his Punjabi background played a big part in discouraging him from admitting he had a problem.

Sanjay, who has been sober for 16 years, says he didn't feel that he could admit he had a weakness, nor that he was feeling lonely and self-medicating with alcohol. He didn't look to the Punjabi community for help, but eventually found Alcoholics Anonymous.

"It would never have occurred to me to go to the community for help with drinking. It was almost the last place I would have gone."

When the first immigrants, who were mostly men, came to the UK from Punjab in the 1950s, 60s and 70s, many found themselves struggling to assimilate being in a new country, often working long hours to send money home to their families.

The stresses of moving to a new culture, the associated language barriers and the racism they faced meant many of these men turned to alcohol to cope. This reliance on alcohol has had generational repercussions.

Jennifer Shergill, an alcohol practitioner from the West Midlands, works with Sikh men and women to manage and overcome addiction. She points to the combination of British binge drinking and the culture of drinking in Punjab, which together create a perfect storm for some of the people accessing support services.

For Harjinder, her husband's heavy drinking had worsening consequences. Although he was becoming increasingly violent towards her, she was still reluctant to seek help.

She says his behaviour was normalised by his family, leaving her feeling almost brainwashed by them into hopelessly accepting the situation. It wasn't until she went to her GP with injuries from the abuse that she realised that what she was experiencing wasn't normal.

Eventually Harjinder called the police and she and her children moved out of the family home to stay with her parents. Even then her husband didn't acknowledge the impact that his drinking was having.

"I think [my husband] knew deep down that what he was doing was wrong but it was almost as if his male pride couldn't admit it."

Jennifer Shergill thinks one of the barriers for people seeking help is the fear of someone finding out. "There is stigma associated with chronic alcohol misuse and they don't want their reputation to be tainted... if there is a dependent drinker in the family what might people think of our family?"

The Shanti Project, external, where Jennifer works, is just one scheme working to tackle this stigma and to provide culturally appropriate services for the Punjabi community in Birmingham.

Others include a volunteer-led Sikh Helpline, external, the Derby Recovery Network, external, BAC-IN, external, and First Step Foundation, which are all doing their part to help tackle alcoholism in a culturally sensitive way.

The Crown Prosecution Service decided not to prosecute Harjinder's husband due to a lack of evidence and, six weeks later, Harjinder and her children returned to the home she shared with her husband.

Her husband's family had visited her to assure her he had stopped drinking and things would be different - so feeling the pressure from both his family and her own, she and her children returned home.

But Harjinder struggled with depression. Her husband hadn't stopped drinking. It was at this point that - prompted by a community psychiatric nurse - she started talking to a counsellor. "I felt quite desperate at times," she says, "but the counselling really helped, I felt that I could carry on."

Harjinder is still living with her husband after more than 20 years of marriage, but their lives are very separate now. Her daughter, now in her 20s, constantly urges her to leave him.

"I've thought about it a lot. A part of me thinks, why bother at this age? But then another part of me thinks: well, if I've got another 20 years of this, that's not good. I think it could happen."

Harjinder and her family members' names have been changed.

If you have been affected by any of the issues discussed in this article, please see the resources listed on BBC Action Line.

- Published15 July 2017

- Published17 June 2017