The Briton fighting 'other people's wars'

- Published

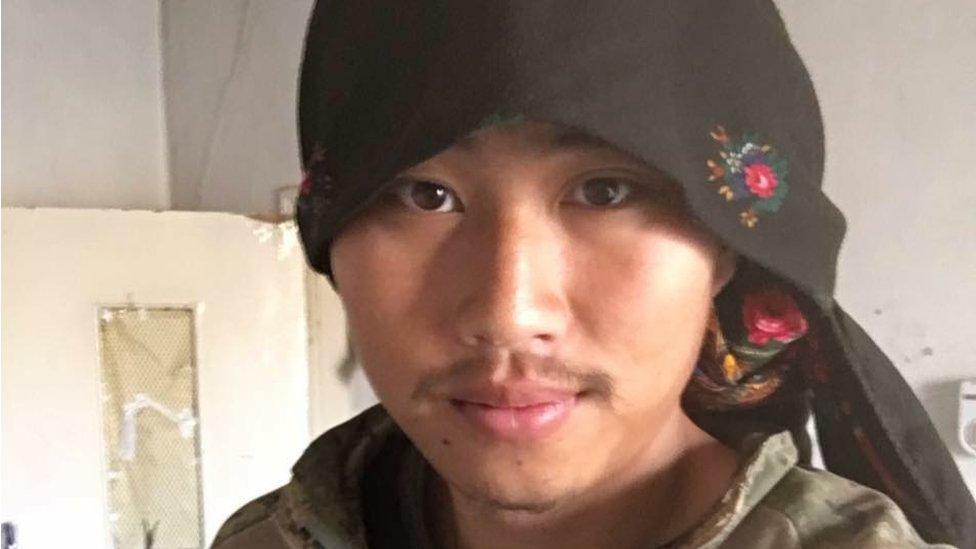

"I call myself a freedom fighter," says John Harding

A number of Britons have travelled to Ukraine to join the ongoing fighting in the east of the country. One Briton who has joined the conflict told the BBC why he considers himself to be a freedom fighter.

John Harding marches along a snow-covered trail outside the Ukrainian capital, Kiev, among a platoon of men dressed in camouflage clothing.

On command, he drops to one knee, adopting a shooting position.

It is a training exercise, for now. He is preparing to take part in the bloody conflict that has ravaged eastern Ukraine for four years.

"Other people's wars aren't a big thing on British media," he says.

"Certainly not as big as they should be in my opinion, so us being here will make people more aware of what's going on."

The 55-year-old ex-Army serviceman from the north-east of England is one of a cohort of Britons who have travelled to join a militia attached to the Ukrainian army.

Camaraderie

He left the UK in February, joining a group called the Georgian National Legion - a group embroiled in the fighting in Ukraine.

Fighters from Europe, the US and Australia have joined up too.

"I'm not going to lie to you, being in battle's a scary thing, and people generally do not enjoy being in a battle," John says.

"But they enjoy the achievement of doing it, and the camaraderie is something that is undeniable."

John Harding (standing far right) with members of his battalion

John's more conventional military experience began when he was aged 16, when he joined the Army after leaving school, serving for nine years.

Later on in civilian life he worked as an engineer.

But in 2015, seeing the rise of the so-called Islamic State (IS), he decided to make something of a return to his military roots and signed up to fight as a volunteer with the Kurds in Syria.

Using social media John made arrangements to join the YPG, the Kurdish armed group that was welcoming hundreds of Western volunteers into its ranks.

He spent months on the front lines with Kurdish fighters in Syria as they captured territory from IS at the height of the jihadist group's rampage.

Heathrow questions

On returning to the UK, he was arrested and questioned by British counter-terrorism police.

It was no surprise, he says, when earlier this year he was again pulled aside for questioning at Heathrow before boarding the flight to Ukraine.

"They say I will be stopped any time I come into or leave the UK," John adds.

He says he was frank with officers about his reason for travelling to Ukraine.

"I don't call myself a mercenary, but I'm sure other people will," he says.

"I call myself a freedom fighter."

The Ukrainian conflict and 'New Russia'

The UN estimates more than 10,000 people have died since fighting in Ukraine began in April 2014

Fighting in Ukraine began in April 2014 after protesters stormed government buildings.

Since then, armed rebels have seized large areas in what is known as the Donbas region in eastern Ukraine. These pro-Russian separatists want to create a breakaway state called Novorossiya, or "New Russia".

Fighting in the Donbas began a month after Russia annexed Ukraine's Crimean peninsula.

Ukraine accuses Russia of arming the separatists in the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and also sending its troops to the region.

Moscow denies this, but admits that Russian "volunteers" are fighting for the rebels.

The horror of the conflict reverberated around the world when Malaysian Airlines flight MH17 was shot down over eastern Ukraine, leaving all 298 people on board dead.

International investigators said the Russian-made missile that downed the passenger plane was brought in from Russia and launched from the rebel-held territory.

Russia has repeatedly denied this.

Fighting between pro-Russian separatists and the Ukrainian army has led to more than 10,000 deaths and displaced more than 1.6 million people over the past four years, says the UN.

Ukraine's neighbour Georgia has a vested interest - Russia supported breakaway provinces in Georgia too in 2008.

When fighting in Donbas began, volunteers from Georgia came to help fight the Russian-backed rebels who were taking control of territory.

Flight MH17 was shot down over Eastern Ukraine in July 2014

While the motivations of foreign fighters are often questioned, John said going to Ukraine was not the result of a desire to kill.

"I'm a conflict medic so you probably can't make that argument with me," he says.

"Some people are politically motivated, some people have the desire to fight a war, there are people that have been ex-military and never been deployed, they feel like they've got something to prove.

"My personal view is that it doesn't really matter what reasons people come for, as long as the results are valid. What isn't welcome is people that come here to kill people. Even though that might be part of the job, it can't be the motivating reason."

Other Britons fighting

John is not the only Briton to have signed up to join the conflict in Ukraine.

The Georgian National Legion proudly displays pictures of its newest recruits on Facebook.

Standing in front of the battalion's flag are Tony, Sean and Ashley - all from the UK. The men say at least six from Britain have joined, but not all wish to be identified.

"In essence the idea of forming the Georgian National Legion was to stand up to Russian aggression," says commander Mamuka Mamulashvili, who says he founded the unit as a volunteer battalion in 2014.

"The Georgian National Legion is now 70% Georgians and 30% others - Germany, USA, UK, Australia, Greece, Azerbaijan, Moldova, Armenia and Israel.

"We can call it a family."

Photos of recruits from Britain on the Georgian National Legion Facebook page

Mamuka insists all would-be fighters are vetted to eliminate individuals who may not be a good fit.

Fighters in the group are paid around $600 a month - roughly £420 - for living expenses, but say they do not class themselves as mercenaries.

The wage, they argue, is far less than those who work for private military companies and may earn tens of thousands of pounds.

The Georgian National Legion says it is funded by the Ukrainian government.

'Do the right thing'

Britons travelling to conflicts overseas has been a concern for the UK authorities.

The Home Office will not comment specifically on fighting in Ukraine, but says it advises against fighting any group abroad.

However, John says he believes helping to oppose the Russian-backed rebels is a just cause.

"When one group tries to impose their will on another group, there are those of us that have the skills to help," he says.

"I feel that in the past what I've done is tried to do the right thing."

- Published24 January 2018

- Published2 February 2017

- Published15 April 2016