Grammar schools: Is selection good for social mobility?

- Published

As the government reiterates its pledge to provide £50m to expand existing grammar schools in England, Labour's shadow education secretary Angela Rayner has criticised the plans as "absurd". She said that the evidence was "clear they do nothing to improve social mobility".

The Department for Education said grammar schools will only get a share of this money if they can show they are taking steps to admit more disadvantaged pupils.

This is a comparatively small pot of money - 0.1% of the total schools budget and funding less than 0.1% of all school places.

There are currently 163 grammar schools in England, out of about 3,500 state-funded secondary schools.

Who ends up at grammar school?

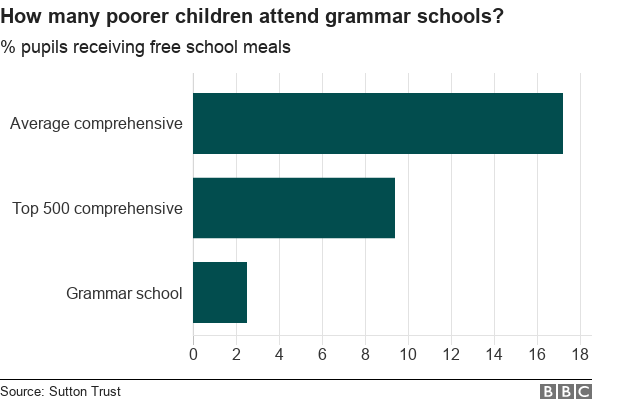

Children receiving free school meals (a common measure of low family income), are far less likely to attend a grammar school.

On average 2.6% of grammar school children received free school meals compared with 13.4% of children across all state secondary schools, according to the latest school census.

There is also evidence that grammars are selecting better-off students over their peers, even when exam results are comparably good.

The Sutton Trust notes that in selective local authorities - in other words those that still operate the grammar system, such as Kent and Buckinghamshire - 66% of non-free school meals children who achieve top English and Maths marks at the end of primary school go on to a grammar school.

In contrast, 40% of similarly high-achieving children who are eligible for free school meals go on to grammar school.

And grammar school children at the moment are more likely than their peers to have been educated outside the state system at primary school.

Do poor children do better at grammars?

Children from more deprived backgrounds on average do better at grammar schools than in the comprehensive system, external, but these schools select a disproportionate number of children from wealthy families.

And those poorer children who live in selective areas - but don't get into grammar school - do worse than those in areas which mainly operate the comprehensive school system.

Research from the University of Durham published in March suggested that grammar schools perform no better than non-selective state schools once their pupils' higher ability and wealth is taken into account.

Do grammar schools make an effort to admit children from lower income families?

At the moment, grammar school intakes are heavily skewed towards children from better-off backgrounds.

In 2016, BBC research looking at the admissions policies of all 163 existing grammar schools in England revealed that fewer than half were doing anything at all to prioritise children on free school meals.

Fewer than 20% were using free school meals as their top priority over other criteria like religious observance, having a sibling at the school or how close they lived.

However, schools review their admissions policies each year and since this investigation was conducted, several have updated them.

The government says the idea is that schools must prove they are taking steps to ensure their intakes are more diverse before they can expand.

One way of doing this is having quotas that mean poorer children who pass the test are prioritised above higher-scoring peers. But they still have to pass and will most likely be up against children who have received extra tuition.

Another way is to have lower pass marks for lower-income children.

In 2016, no grammar school weighted test scores in favour of poorer children, although three schools did still consider for admittance children receiving free school meals who scored up to 10 points below the pass mark.

And they still have to encourage poorer children to sit the exam in the first place.

Are grammars just playing catch-up?

Under the current law, new grammar schools cannot open but existing ones can expand.

Education Secretary Damian Hinds said the new expansion would simply allow grammar schools to do what other schools have already been allowed to do - create new places where there is demand.

He said the expansion would "give parents greater choice in looking at schools that are right for their family - and give children of all backgrounds access to a world-class education".

England's grammar schools have already been growing.

A BBC analysis in January found that the number of pupils aged 11-15 in England's grammar schools had gone from 110,600 in 2009-10 to 118,200 in 2016-17 - a 7% growth at a time when the number of 11 to 15-year-olds in the areas with grammar schools fell by 2.5%. Pupils tend to travel further to attend grammar schools than they do to attend comprehensives.

And they are often not in areas most in need of more secondary places.