Death in data: What happens at the end of life?

- Published

Scientists are expecting a spike in deaths in the coming years. As life expectancies increased, the number of people dying fell - but those deaths were merely delayed.

With people living longer, and often spending more time in ill-health, the Dying Matters Coalition, external wants to encourage people to talk about their wishes towards the end of their life, including where they want to die.

"Talking about dying makes it more likely that you, or your loved one, will die as you might have wished. And it will make it easier for your loved ones if they know you have had a 'good death'," the group of end-of-life-care charities said.

Where to die?

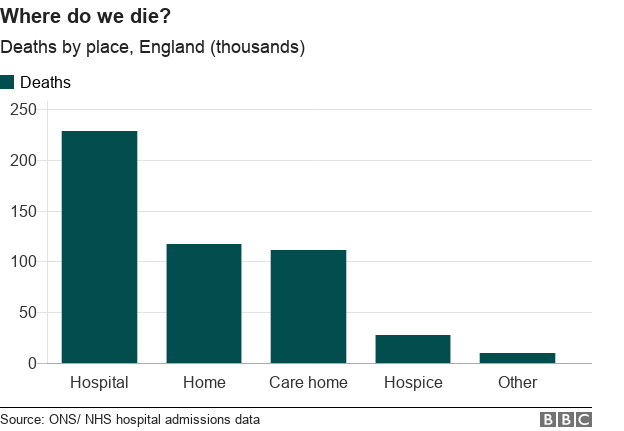

Surveys repeatedly find most people want to die at home. But in reality the most common place to die is in hospital.

Almost half of the deaths in England last year were in hospital, less than a quarter at home, with most of the remainder in a care home or hospice.

What happens to human remains?

Dying wishes don't just extend to where you die but to what happens to your body after death too.

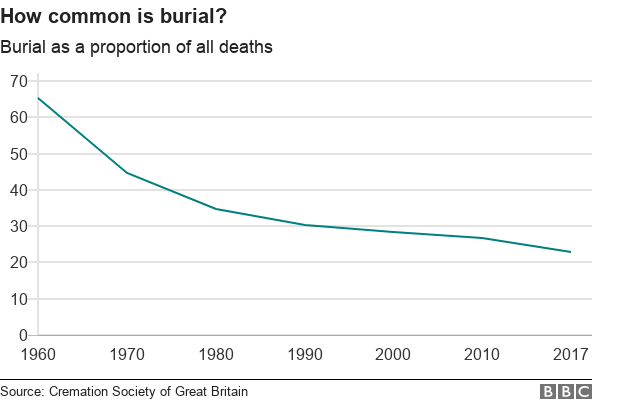

Cremation overtook burial in the UK in the late-1960s as the most popular way to dispose of human remains, and more than doubled in popularity between 1960 and 1990.

Since then it has remained fairly stable at about three-quarters of the deceased being cremated, although it has been creeping up gradually year on year - in 2017 it hit 77%.

Although cremation is thought to be more environmentally friendly, it is not without its own costs. The process requires energy. And burning bodies releases carbon dioxide into the atmosphere.

There are hundreds of "green" burial grounds in Britain where coffins must be biodegradable and no embalming fluid or headstone markers are permitted. Instead, loved ones of the deceased often plant trees as a memorial.

The Association of Natural Burial Grounds says: "Many people nowadays are conscious of our impact on the environment and wish to be as careful in death as they have been during their lives to be as environmentally friendly as possible."

At natural burial grounds, bodies are generally buried in shallow graves to help them degrade quickly and release less methane - a greenhouse gas.

Some people want to go further than this.

A form of "water cremation" is currently available in parts of the US and Canada, and could come to the UK.

This eco-friendly method uses an alkaline solution made with potassium hydroxide to dissolve the body, leaving just the skeleton, which is then dried and pulverised to a powder.

Sandwell Council, in the West Midlands, was granted planning permission to introduce a water cremation service, but these plans are currently on hold because of environmental concerns.

In December 2017, water providers membership body Water UK intervened and said it feared "liquefied remains of the dead going into the water system".

Cremation by fire or burial remain the two options for most people, but those that want to do something a bit different could opt to have their ashes turned into a diamond, external or vinyl record, external, displayed in paperweight, exploded in a firework, external or shot into space.

The cost of death

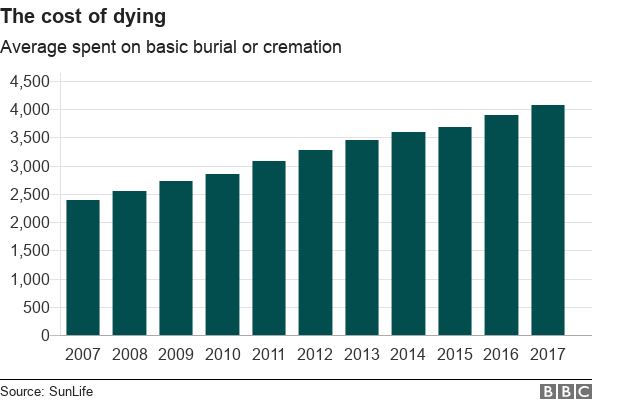

Traditional cremation is cheaper than burial, particularly as space is short, driving up the cost of grave plots. But the cost of funerals in general has been rising.

Insurance firm SunLife, which produces an annual report on the cost of funerals, says prices have risen 70% in a decade.

It put this down to lack of space and the rising cost of land as well as fuel prices and cuts to local authority budgets leading to reduced subsidies for burials and crematoria.

A survey of 45 counties, conducted by the Society of Local Council Clerks,, external found half of respondents' local council run cemeteries would be full in 10 years and half of Church of England graveyards surveyed had already been formally closed to new burials.

The same problem faces Islamic burial sites.

Mohamed Omer, of the Gardens of Peace cemetery in north-east London, says the problem is compounded by a growing population and by the fact that Muslims do not cremate their dead.

The Jewish community also does not traditionally practise cremation. David Leibling, chairman of the Joint Jewish Burial Society, says all of the four largest Jewish burial organisations have acquired extra space in recent years.

However, he says it's not such a problem for the community since synagogue members pay for their burial plots through their membership. This means the organisation can predict how many people it is going to have to bury.

"As we serve defined membership we can make accurate estimates of the space we need," he says.

What about our digital legacy?

There are growing concerns over what will happen to people's social media profiles after they die.

The Digital Legacy Association, external is working with lawyers to produce guidelines on creating a digital will, setting out people's wishes for what happens to social media profiles - and "digital assets" such as music libraries - after death.

Three-quarters of respondents to the DLA's annual survey say it's important to them to be able to view a loved one's social media profile after their death.

But almost no-one responding to the survey had used a function to nominate a digital next of kin, such as Facebook's legacy contact or Google's inactive account manager functions.

Both Facebook and Instagram allow family and friends to request the deceased's account is turned into a memorial page, while Twitter says loved ones can request the deactivation of a "deceased or incapacitated person's account".