The door-knock that brought back years of abuse

- Published

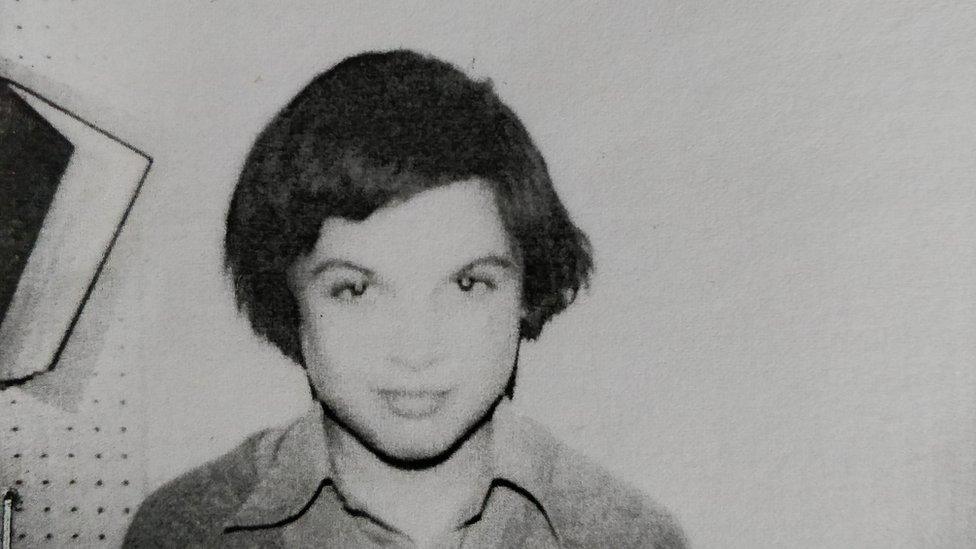

Mark's first day at Grafton Close, a council-run children's home, was in December 1980

A knock on the door by two detectives changed everything for Mark, bringing back the horrors of sexual abuse he had suffered as a child. Like other survivors of child abuse, he says he found it hard to get any support afterwards.

The black and white photo of Mark was taken in December 1980 on his first day at Grafton Close, a council-run children's home in south-west London. Weighing just 5st 8lb and measuring just 5ft 2in tall, he looks younger than his 14 years.

His young life was already troubled and it was about to get a lot worse.

Now, 38 years later, Mark is still dealing with the consequences.

"When I was a kid, I was as kind-hearted a child as you can possibly imagine," he says.

"What happened to that child is so horrendously wrong, and it's horrendously wrong that it should just be allowed to continue."

Mark was sexually abused by a manager at the children's home. Other children were abused there too and some were taken elsewhere to be abused.

Although he was small and vulnerable, Mark was a very bright and articulate boy, who managed to cope by outsmarting people. "I used language as a weapon," he says.

He had few qualifications but in his 20s and 30s made a successful career for himself working in commercial radio sales.

He explains his coping strategy as managing to lock away his terrible childhood traumas in a box marked: "Do not open ever."

But it all came crashing to a halt in January 2013 when the police came knocking on his door.

As Mark re-lived the traumatic events of his youth, he became very anxious and suffered panic attacks

At the time, the UK was going through a collective panic over child abuse.

It was not long after the revelations about Jimmy Savile, and the police were investigating a series of allegations about high-profile paedophiles operating in Westminster during the 1970s and 1980s.

The visit, by two officers from the Metropolitan Police, to Mark's house in the Manchester area came out of the blue. During the visit - and in a subsequent formal interview - they asked about the abuse he suffered.

Mark said his carefully constructed mental box was now in ruins - its dark secrets scattered over the floor for everyone to see. He says the police left him to deal with the consequences, and offered no support.

"I went through 18 months to two years of deep, deep depression," he says. "It's like you're gradually walking through a tunnel, and your friends become further away - they visit less.

"You've got a choice - a choice to either fight to get back to the light, or let it drift away. I fought to get back to the light."

Mark says he suffered from suicidal thoughts, and became very anxious. He suffered panic attacks in public places, and was terrified of people even walking past his front door.

Shortly after the police visit he discovered to his horror that someone had posted the names of a list of child abuse victims online, and that his name was listed among them. Another post described him wrongly as a "rent boy".

Mark became embroiled in a long battle with the police to get them to force the websites to remove the postings, but the police failed to act. He eventually managed to get them removed himself.

The man who abused him was charged with sexual offences, but he died shortly before the case came to court. Mark would have been a victim and witness at the trial but never got his day in court.

Clinical psychologist Vanesssa Fay says she helped Mark work through some "very self-critical beliefs"

He has recently completed a 24-week course of Cognitive Analytic Therapy, delivered by clinical psychologist Vanessa Fay, of the Greater Manchester Mental Health NHS Foundation Trust.

"That knock on the door from the police changed everything for Mark. He couldn't push it down anymore, and how painful it is. He wasn't aware of how complicated and nuanced that impact can be on relationships, and how he related to himself," she says.

Mark has been diagnosed as suffering from Complex Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (CPTSD), also known as Complex Trauma. He says he managed to access a course of treatment only after a relentless struggle with his GP for support.

Complex Trauma is poorly understood, rarely recognised, and few psychologists are trained to treat it. The condition is not even officially recognised but is expected to be included as a distinct category of PTSD in an international classification system known as ICD-11, published by the World Health Organization.

Bryony Farrant, chief psychologist to the Independent Inquiry into Child Sexual Abuse, external, said official recognition will make a big difference to survivors of abuse and therapists.

"It would mean professionals will need to be trained and have an understanding of complex trauma - what it looks like, what causes it, and identified treatments and support. But for victims and survivors it would be particularly important because often with the abuse they have experienced, part of it is about secrecy, about that person being silenced, and disempowered."

Mark believes his therapy has helped him but is worried he will not be able to access any further NHS support

Mark blames the police for "re-traumatising" him and failing to offer support. He is most upset with their failure to deal with the online postings naming him publicly as a child abuse victim.

He made a series of complaints to the police and the Independent Police Complaints Commission, and the Metropolitan Police eventually apologised. They admitted their systems were at fault and he should have had more support. But they said no individual officer was at fault and there was no police misconduct.

The Met said in a statement to the BBC that officers are trained to be sensitive to victims, and they are directed to support agencies.

Napac - the National Association for People Abused in Childhood - says there are more than 11 million adult survivors of child abuse in the UK, and they deserve much better specialist support.

Research by the NSPCC in 2011 found that 25% of 18-24 year olds suffered severe maltreatment including sexual abuse as children.

Mark Samaru believes his therapy has helped him process the ordeal he went through. He is also very aware that most survivors get nowhere near the support he has fought to get.

"It's a measure of our society how we treat the most vulnerable," he says. "Nobody who's been abused in childhood deserves it, and yet they all deserve as much support as society can give them. And they're not getting it."

Listen to Andrew Bomford's full piece on BBC Radio 4's World at One.

- Published25 April 2018

- Published27 March 2018

- Published9 August 2017