The blame game: Getting divorced in the UK

- Published

Divorce lawyer drama The Split comes to a conclusion on Tuesday while, in the real world, a couple await the verdict in what has been described as the most significant divorce case of the century.

Throughout the UK there is one legal ground for divorce: the "irretrievable breakdown" of a marriage.

And there are three main reasons you can give to show a marriage has irretrievably broken down:

Adultery

Unreasonable behaviour

Separation

The first two are about attributing blame.

In the case of separation, a couple have to prove only that they have been living apart (and that can include living in the same house provided they are not sharing a bed or living as a couple) for a certain period of time.

In England and Wales, it's two years where both the parties agree and five years if one of the couple does not consent to the divorce.

Desertion can also be grounds for divorce in England and Wales, if the party has been abandoned for more than two years without agreement or good reason.

In Scotland, the waiting period is shorter - one year if both agree and two years if they don't.

For the "fault-based" grounds, the process can take more like three-to-six months.

Separation is sometimes referred to as "no-fault divorce" because it doesn't involve ascribing blame to any one party.

Couples cannot use adultery as a ground for divorce if they lived together as a couple for six months after the infidelity was known about.

And because adultery is classified in law as extra-marital sex between a man and a woman, this reason cannot be used by same-sex couples - they would have to rely on the "unreasonable behaviour" argument instead.

The figures presented in these charts all relate to opposite-sex couples. Since gay marriage was legalised in 2014, there has been a small number of same-sex couples divorcing (22 in 2015 and 112 in 2016, out of a total of 11,000 same-sex marriages).

Many lawyers argue that the UK should move to an entirely "no fault" system where instead of having to give one of these reasons, couples could just notify the courts that they wish to divorce and start the process that way.

They say that in England and Wales in particular, the waiting time for "no fault" divorce - for those couples who rely on separation as their reason - is too long.

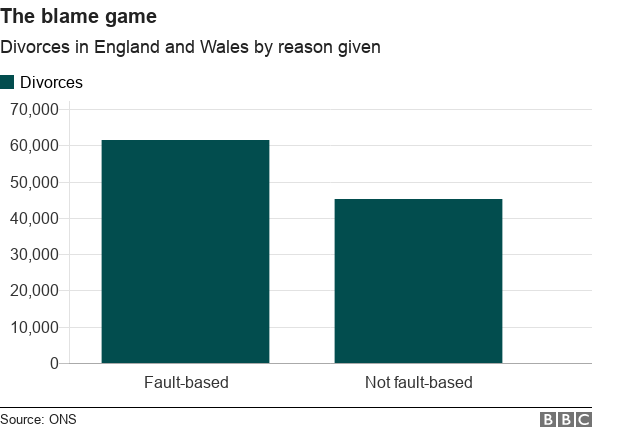

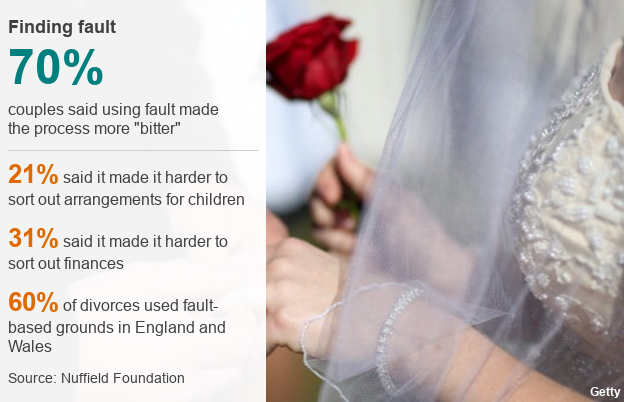

Law professor Liz Trinder says in Scotland, where there are shorter waiting times for "no fault" divorces, just 6% of divorcing couples rely on the fault-based grounds of adultery or unreasonable behaviour. In England and Wales, it's 60%.

She believes the long waiting times for a divorce on grounds of separation can encourage couples to attribute blame, to speed matters up, but this makes divorce proceedings more acrimonious.

And during the period of separation, it's often difficult for couples to sort out their finances - selling the family home, for example.

She surveyed about 1,000 divorced people, external and found 43% who had been identified as being at fault by their spouse disagreed with the reasons cited for the marriage breakdown.

She says the judicial system doesn't have time to question the allegations or demand any real proof, meaning accusations go unquestioned, even if the accused denies they have behaved unreasonably or had an affair.

"There's a lot of manipulation of the system and it undermines confidence in the whole thing," she says.

Some are concerned that speeding up the process could rob people of valuable thinking time in which they might decide not to go through with it.

But Professor Trinder says: "People take a long time to decide before they get to file for divorce. They will already have been thinking about it for a long time."

Family lawyer Kate Landells says fault-based divorce is an "artificial construct that you have to go through just to start the process".

She says it "creates an antagonistic start to what is already a really sad time", although she adds that attributing responsibility can be "emotionally useful", especially for the party who feels they've been wronged.

"But it's often not as clear-cut as that," she says.

Do half of marriages end in divorce?

The Office for National Statistics (ONS) estimated in 2012 that 42% of marriages in England and Wales would end in divorce, external. That's the latest estimate we have of the likelihood of married people getting divorced over the course of their lifetime.

But the divorce rate in each individual year is much lower, and has continued to fall since that estimate was produced - from 10.1% of marriages in 2012 to 8.5% in 2015.

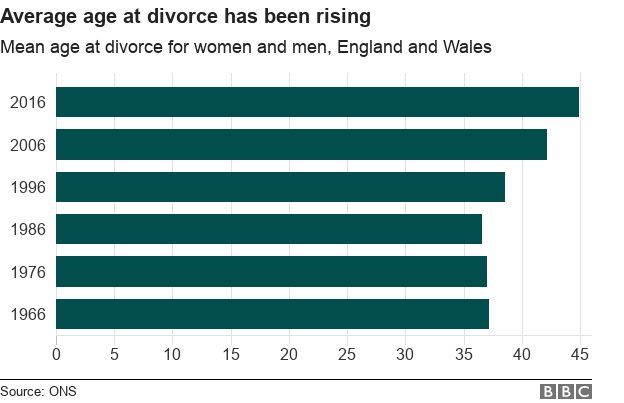

Fewer of us are getting divorced now, external, and part of that fall is down to fewer people getting married. There are growing numbers, both of single people and of couples living together without tying the knot.

However, the divorce rate has also gone down.

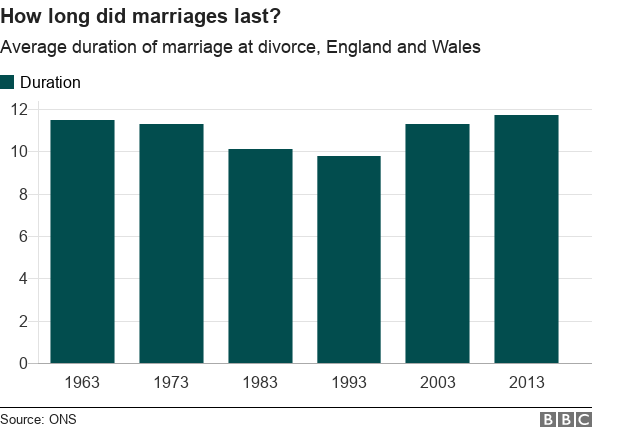

So it looks like those of us who do choose to marry are more likely to go the distance now than 20 years ago.