What lies beneath England's allegiances and rivalries?

- Published

Beneath the veneer of national identity, England is an elaborate tapestry of allegiances and rivalries.

For centuries, bureaucrats have drawn lines on the map without understanding the invisible ley lines of belonging that criss-cross the English countryside. There are deep loyalties to ancient counties, proud cities and towns, even legendary kingdoms.

The survey for The English Question, the largest and most comprehensive of its kind ever conducted, reveals something of these hidden ties and bonds.

The English counties, some with stories that predate England itself, are a strong source of identity for roughly half the population.

The allegiance may be to an ancient or historic county that planners have carved up, redesigned or obliterated, but these pre-industrial administrations clearly still have a place in the hearts of many.

Yorkshire, with its Viking origins and Norman design, inspires the deepest passions of all. Three quarters of people from York and the Ridings feel a strong allegiance to their county. Only one other county comes close to such levels of belonging - Yorkshire's great rival, Lancashire.

The Tour de Yorkshire is an occasion for an outpouring of pride in the county

At the Tour de Yorkshire bicycle race this year, souvenir-sellers were doing brisk business in county flags. Local pubs had strewn Yorkshire puddings on strings with special deals on creamy-headed Yorkshire beer.

At a local primary school on the route, teachers had devoted the day to teaching the children about their Yorkshire birthright. Welly-wanging classes, Yorkshire pudding races and sheep dyed in the county colours were all part of the indoctrination process.

It may be more than 500 years since the War of the Roses, but the heraldic white rose of the Yorkists still casts its spell.

Our survey asked people to identify symbols, characteristics or ideas that contributed to their sense of local belonging and the heraldic white rose was mentioned third after countryside and friendliness.

In describing their sense of belonging, many people also wrote of "Yorkshireness", a quality variously described as straight-talking, plain-speaking, hard-working, friendly and supportive. The Yorkshire identity is rich with values of resilience and community.

English counties that fail to inspire such levels of affection include those in the area sometimes called the South Midlands: Oxfordshire, Hertfordshire, Bedfordshire, Northamptonshire and Buckinghamshire - places now firmly within the gravitational pull of London.

Few in the capital itself have a very strong county identity and it does seem the city has a dulling effect on county sentiment.

Even though it is a major world city, few London-dwellers have a strong county allegiance

Third and fourth in terms of county allegiance are Cornwall and Cumbria, both protected by geography from London's sphere of influence.

If county identities reflect the old boundaries of a bucolic feudal landscape, city identities were forged in the furnaces of the industrial revolution. The strongest are in the north of England, and nowhere stronger than in Newcastle.

Roughly half of people in England say they have a close connection to a city, town or village. Among Geordies, seven out of 10 report a strong city identity - the highest of anywhere.

Press them on what that means and people will talk about the River Tyne and its bridges, a passion for football and the nutty sweetness of brown ale.

People in Newcastle have the strongest identity of those in any English region

But it is also about community and friendship through tough times. The Geordie identity is founded on collective hardship.

The only city that comes close to Newcastle's sense of itself is some 10 miles south and east, its great rival, Sunderland.

We define ourselves by where we are from but also by where we are not from. The strongest identities seem to require a rival, although sometimes it is not reciprocated.

There is evidence from the survey that people in the town of Rugby, for example, regard Coventry as their rival. But the people of Coventry tend to see Birmingham as the true adversary.

Birmingham, meanwhile, sees Manchester as the competition. Manchester, though, is preoccupied by a reciprocal and intense rivalry with Liverpool.

Liverpool retains its own special identity

Identity tends to be built around a narrative, the collective story of a place or region rich in shared values and social history. The strongest identities tend to be those laced with struggle and a sense of grievance. Poverty binds communities in a way that wealth rarely does.

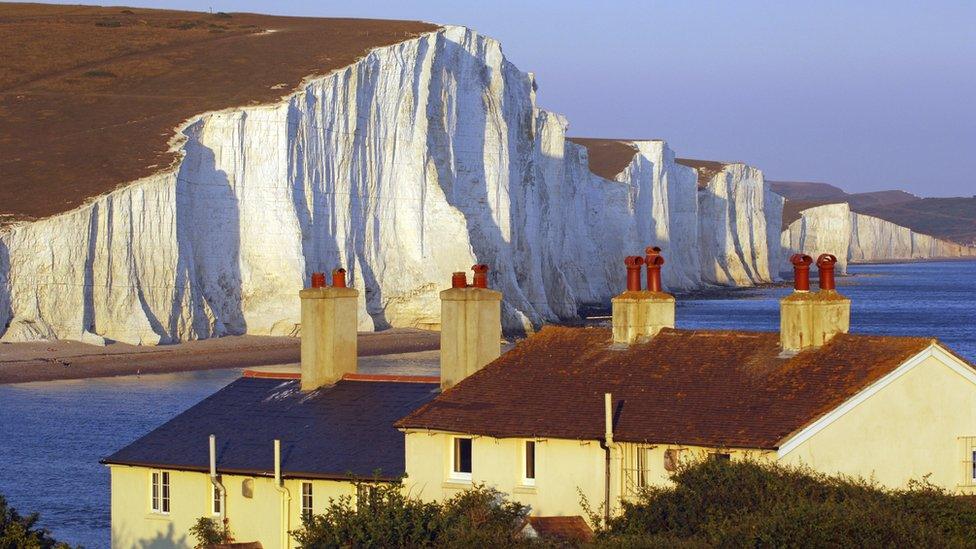

People cite landscape and countryside as very important in shaping their sense of identity. Local hills and moors, fields and hedgerows seem to influence our relationship with place much more than buildings and roads. Partly this is aesthetic, but it is also about a link to the ancient.

We can imagine our ancestors gazing at the same view, sheltering in the same forest, walking on the same path. It can be no surprise that our relationship with the land we live upon is intensified by the rural more than the urban.

Two-thirds of people living in some northern towns and cities, for example, say their identity is strongly shaped by the landscape, while a minority say the same for their area's industrial heritage.

In some rural parts of England that relationship to landscape is strongly linked to its fertility and productivity. The people of Somerset are rightly proud of their famous orchards and cider, their dairy herds and cheeses.

Legendary figures, like Somerset's Apple Tree Man, remain popular

In the search for differentiation in a globalised world, the provenance of agricultural products is as important for local identity as it is for national marketing.

Somerset's link to the soil also has a metaphysical dimension, an identity that associates with dragons and wassails. The mythical Apple Tree Man, the pagan spirit invoked to bless the cider harvest, is still part of the county story.

If anything, in recent times pre-Christian tradition and Arthurian legend have become more important in these parts.

Sub-national identities are supercharged by those characteristics that have claim to the uniquely local, particularly if their roots drink from the subterranean waters of the ancient.

Accents and dialects are particularly important to our sense of who we are, a fact that may help explain how they have survived the homogenising forces of mobility and connectivity. They are adopted, cherished, protected and reverently passed on.

We have never really understood the way these forces play across the English geography. The identities of England, it seems to me, are the keys to unlocking the enigma of "this sceptred isle".