Why working from home was never an easy option

- Published

Working from home is often portrayed as offering the best chance of balancing a career and home life. But has it ever really lived up to expectations?

A rosy picture of avoiding the commute and contentedly tapping away on a laptop at the kitchen table is often conjured up when we think of working from home.

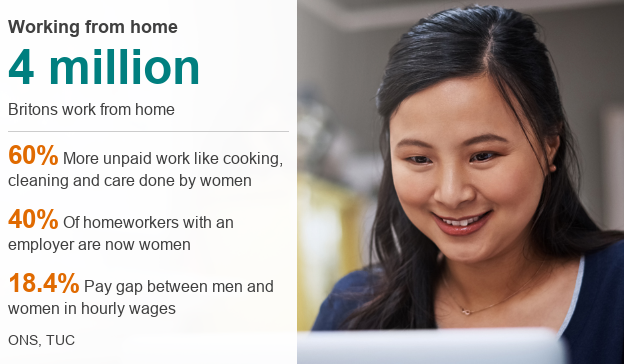

It is something that more than four million Britons now do on a regular basis and a way of working often associated with flexible lifestyles and greater freedom.

Although men are more likely to work from home, four out of 10 homeworkers with an employer, external are women, a proportion that has grown in recent years.

But for some women, the reality of balancing work with an unequal share of domestic duties can mean working at home falls short of expectations.

It's a situation which arguably hasn't changed for 200 years - and the past can tell us a great deal about why things are as they are today.

The line between 'home' and 'work'

Domestic life changed for good with the coming of the factories after 1800 - putting women firmly in charge of the home and children, even as many went out to work.

Until the Industrial Revolution, there had not been a rigid line between "home" and "work", with a large proportion of the population living off the land, or working in cottage-based industries like spinning and weaving.

Yet the home remained a place where many women had to earn money.

Women often took in work to supplement a husband's low wage in the factories - or, in the case of widows, unmarried mothers and deserted wives, to replace it entirely.

Some preferred it to the option of working in a factory themselves, taking on jobs like sewing shirts, carding buttons and assembling boxes and paper bags.

As Mrs Cole, a corset-maker from Bristol, told a Parliamentary Committee in 1908: "I would rather work at home than I would in a factory, because you are better off with 8 shillings at home than you are with 15 shillings in a factory."

The Census never counted these women with any precision, but it seems likely that there were at least several hundred thousand by the end of the 19th Century in large cities like London, Birmingham, Leeds and Glasgow.

Even though much of this work required great skill, it was usually poorly paid, with middle-class reformers campaigning for an end to "sweating" - work with excessively long hours, insanitary conditions and pay below subsistence levels.

Racism on the streets

Low pay for many homeworkers continued throughout the 20th Century, despite the best efforts of campaigners and the introduction of minimum pay legislation.

During World War Two, the government recruited as many as 20,000 outworkers to assemble military hardware components in their homes and village halls.

And an official inquiry in 1948 estimated that there were up to 60,000 homeworkers in industries like glove-making, hosiery and tailoring.

More like this:

In the 1970s and 1980s, there was a particular resurgence in the clothing trades, which employed many migrant women from the Indian sub-continent to meet demand for cheap fashion.

Earning money by sewing garments at home could be attractive for those with children to look after, little English and, for some, first-hand experience of racism on the streets.

Yet homeworkers were still at risk of exploitation, with many isolated and unaware of their rights as employees.

There was often little control over the quantity of work, with rush orders one week and none the next.

For many, the balance between work and family life was a myth.

As one mother reflected in the early 1990s: "I got bad-tempered because I knew I had to finish the work, working till late. If the children woke in the evening, I got annoyed. Not with the kids, but because I knew I didn't have the time to spare."

Early pioneers

Many Victorian women had to take on poorly-paid work to make up for their husband's low wages

However, not all forms of homeworking have been physically gruelling and poorly paid.

Writing, painting or sculpting were respectable pursuits for educated women from the early 19th Century.

With servants to see to housework and children attended by nurses, or away at boarding school, such women had time to follow these occupations and even to earn money from them.

In 1865, the Victorian feminist campaigner Bessie Rayner Parkes observed of writing as a profession: "Women demanded work such as they could perform at home, and ready pay upon performance; the two wants met, and the female sex has become a very important element in the fourth estate."

Pioneer female doctors often established private practices from their homes, which helped to distract public attention from their "unwomanly" professional ambition.

And large numbers of women ran shops, pubs and boarding houses from their homes, either alone or with husbands.

The rise of the 'mumpreneur'

In some respects, these industrious Victorian women are the predecessors to the freelancers, business owners and "mumpreneurs" who dominate our contemporary vision of homeworking.

But their history points to another, less comforting, continuity between past and present.

Then, as now, many women who chose to work at home did so because of limited work opportunities elsewhere and family pressures.

A shortage of affordable childcare, coupled with a gender pay gap of 18%, can make homeworking the most attractive option.

Women perform 60% more unpaid work in the home than men,, external including cooking, cleaning and childcare.

Today, parents and carers have a right to request flexible working arrangements, although employers are not obliged to allow employees to work at home.

Of course, there are many women - and men - who work at home happily and enjoy success in doing so.

But it would be a mistake to lose sight of how we first came to experience the persistent inequalities which make homeworking so attractive in the first place.

About this piece

This analysis piece was commissioned by the BBC from an expert working for an outside organisation.

Dr Helen McCarthy, external is Reader in Modern British History at Queen Mary University of London. She is the editor of the journal Twentieth Century British History and writes on the history of working mothers.

These Four Walls, an exhibition on the theme of women's homeworking created by Dr McCarthy and photographer Leonora Saunders, is on display as part of the British Academy's Summer Showcase., external

Follow her @HistorianHelen, external.

Edited by Duncan Walker