'The prisoners can sense your fear'

- Published

Neil Samworth described the wards at HMP Manchester as "lawless" and "chaotic"

Neil Samworth used to love his job as a prison officer, but more than a decade after joining he says it left him angry, frustrated and living with post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). It meant he had to leave.

"Prisoners can sense fear in people's faces," the former guard tells the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme, remembering how he was the subject of their animosity.

There was a time when he was confident in the role, having started as a prison officer in 2001, and felt his experience gave him the edge over the inmates he looked after.

But a shoulder injury that occurred during a physical restraint in 2015 at HMP Manchester - formerly known as Strangeways - changed all that.

The injury left him unable to work for several weeks but much greater than that was the psychological impact.

The wards had become "chaotic" and "lawless", he says, containing "extremely violent" prisoners with not enough guards on duty should the atmosphere turn sour.

'Very confrontational'

The time off to reflect led him to become "angry, frustrated" and develop anxiety problems.

"It got worse over a couple of months," he says, "and I referred myself to psychological services. I talked and talked and everything came out.

"I became very confrontational, which isn't me.

"When that happens [while on duty], prisoners become hostile and start shouting in your face," he says, which only made matters worse.

"We were so short-staffed, and when there was an incident it was hard to deal with, so they were being locked up more and more to keep control."

HMP Manchester was described as "squalid" in a 2017 report by the Independent Monitoring Board

Then they're "frustrated", he says, which escalates the tension.

In 2017, there were 8,429 assaults on staff in England and Wales, Ministry of Justice figures show,, external up 23% from the previous year. Of these, 864 were classed as serious.

"I got assaulted a few times in prison," says Mr Samworth - who has written the book Strangeways about his experience.

"I was punched, bitten and spat on so many times. It's scary."

By mid-2016, having being involved in a narrowly-averted riot, he took early retirement on mental health grounds.

He had suffered from anxiety and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) from his experiences at the prison.

'Vermin-infested'

HMP Manchester, a high-security prison, houses around 1,200 male inmates.

A 2017 report by the Independent Monitoring Board said it was "squalid, vermin-infested" and "reminiscent of Dickensian England".

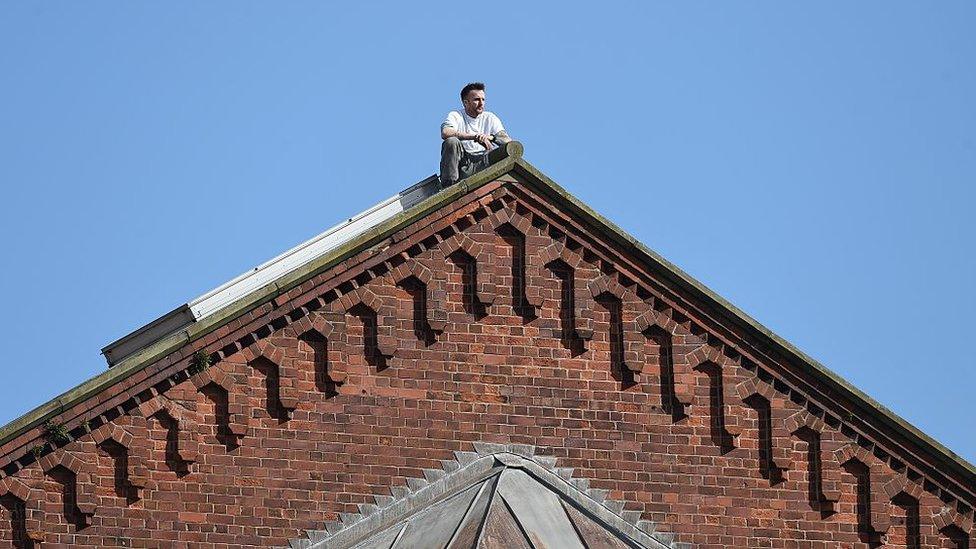

In September 2015, a convicted murderer spent more than 60 hours on top of a Manchester prison because, he later told a jury, "no-one was listening" to his concerns about prison conditions.

Convicted murderer Stuart Horner spent 60 hours on top of the prison's roof

During Mr Samworth's time there, he worked on the prison's most-populated wing, with inmates on three different levels.

It was home, he says, to both "normal prisoners" and those "who were locked up for radicalisation and terrorist incidents".

He believes it led to many of the general inmates becoming radicalised.

"There were lots of impressionable people. One lad said, 'I'm fighting a 10-year sentence and I can't do it all on my own'," he remembers.

"Others were getting really into it - all they were talking about was blowing things up."

Child killers

Mr Samworth also worked on the hospital's medical wing, "where you had everything from cancer patients and alcohol and drug detoxes to mental health patients - plus extremely violent and obstructive prisoners".

Many would be on medication, but he says there was little officers could do if they refused to take it.

"We saw people incredibly unwell, with serious self-harming.

"Someone who's detoxing will be bouncing off walls, hallucinating, and be extremely violent.

"We had child killers, paedophiles, violent rapists [on the ward] and there was no support from the prison really. We'd just deal with it in the unit."

The Ministry of Justice said more than 14,300 prison staff had "already received new suicide and self-harm reduction training on top of the safer custody training already provided across the prisons estate".

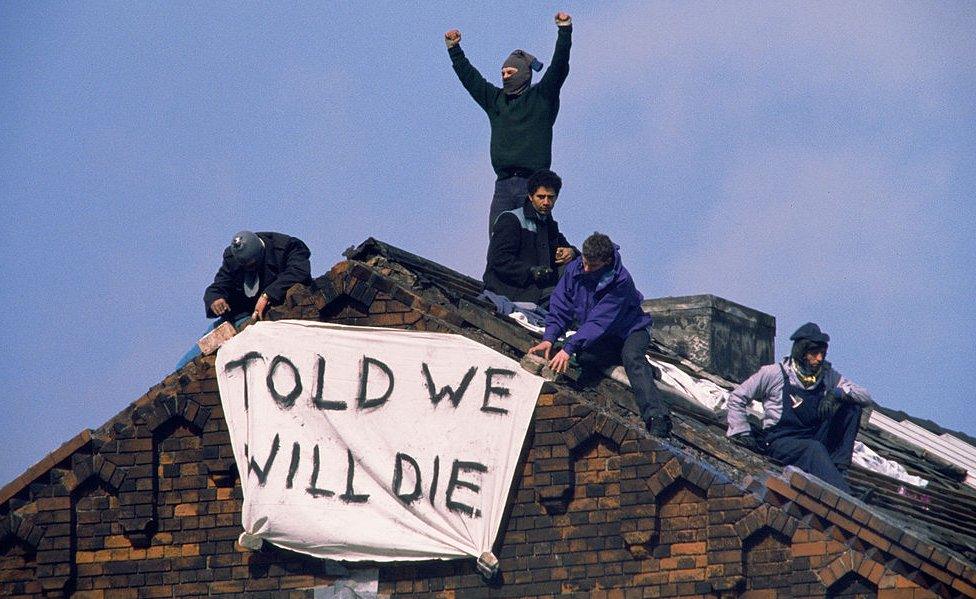

In 1990, before Mr Samworth worked there, a 25-day riot took place at Strangeways - the longest in British penal history

Mr Samworth fears the strain on prison officers is now getting worse, with many experienced staff leaving in recent years.

"A massive part of prison [as a guard] was dynamic security, and knowing your prisoners well," he says.

"There are thousands of relationships with prisoners and staff and that's what kept prisons safe - as you knew what was going on, who was getting bullied."

But newly-recruited officers - as well as not having this knowledge, he says - are no longer "allowed time to adjust" on first joining the profession.

"You're put in charge straight away."

The Ministry of Justice said it had "recruited over 3,000 prison officers in the last 18 months to improve safety" in England and Wales, adding that it had increased prison officer pay by an average of 1.7% to help retain experienced staff.

It is now two-and-a-half years since Mr Samworth himself exited the profession, and he says he has only just started to feel like a "normal person" again following his mental health problems.

"I did love the job but it got worse," he concludes.

"So I'm glad in a way I left."

Watch the BBC's Victoria Derbyshire programme on weekdays between 09:00 and 11:00 on BBC Two and the BBC News Channel in the UK.

- Published10 July 2017

- Published24 January 2018