Caving in the UK: 'The last true wilderness'

- Published

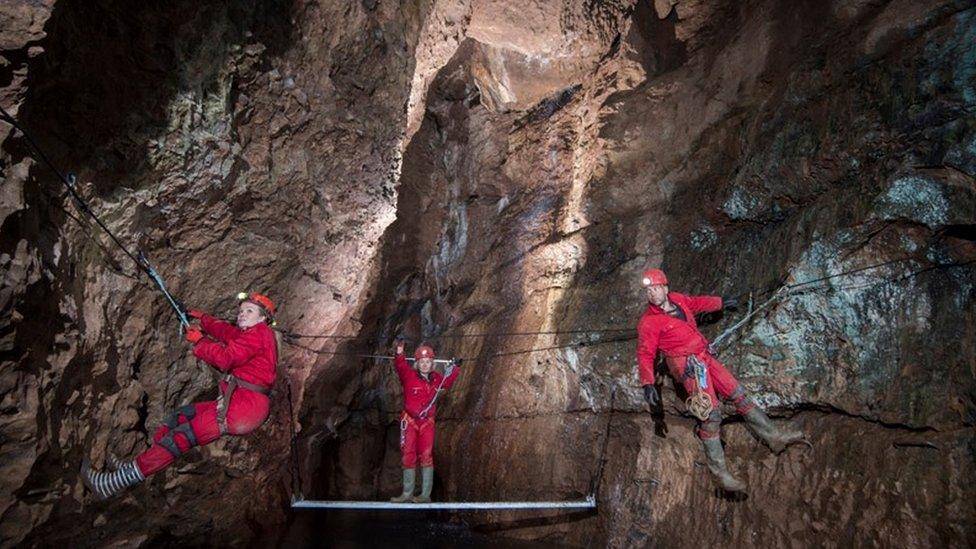

The caves at Wild Wookey in Wells, Somerset, are a popular destination

The rescue of 12 boys and their football coach in Thailand has highlighted the risks of caving - but also Britain's expertise in the field.

Two British expert cave divers, John Volanthen and Richard Stanton, were the first to find the boys who had been trapped underground for nine days.

There are up to 4,000 regular cavers in the UK. Many say that despite the risks, accidents are rare. So what makes it so popular?

"I was lying on my back and moving through a pool of water, with a rock ceiling just above my face," says David Morgan, recalling one of his strongest memories of caving as a child.

"The sense of achievement of getting out the other side without panicking is tangible to this day."

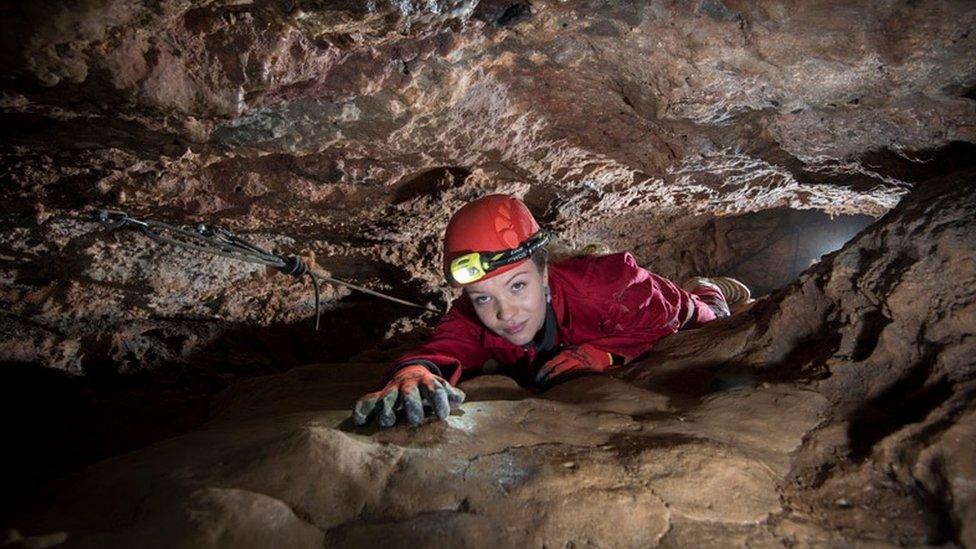

The 23-year old, who is a member of Exeter University's caving club, describes another caving technique called a "squeeze".

"It was a long crawl on my belly with cave walls only inches from my body above, below, and beside."

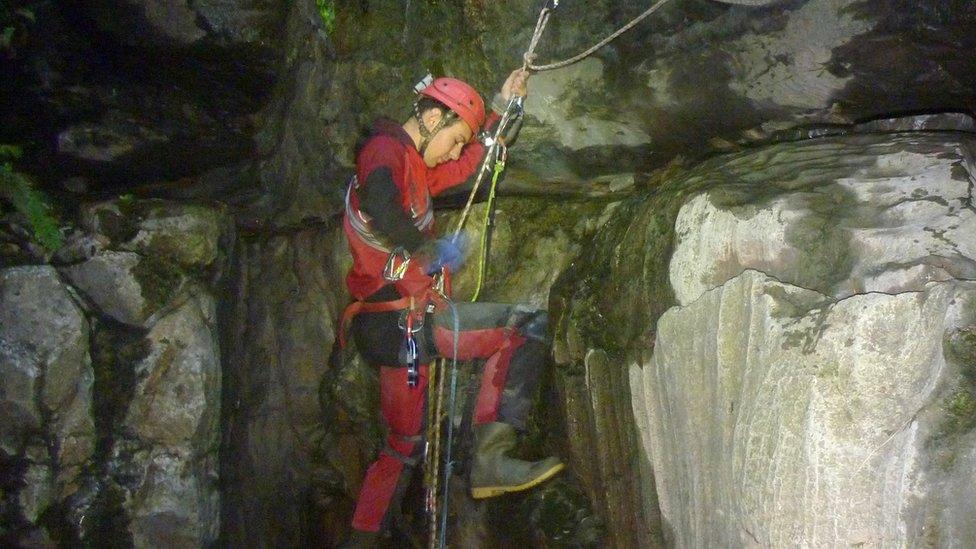

Caving can include hiking, climbing, bouldering, abseiling down an abyss, camping overnight and diving into icy-cold lakes.

For many people who have never tried it, the thought of going underground fills them with at best unease - and at worst, dread.

But Britain is rich in caves - the majority in the Yorkshire Dales, the Peak District in Derbyshire, the Brecon Beacons in south Wales and the Mendip Hills in Somerset.

Some caves have chambers large enough to fit a cathedral, while others are a narrow squeeze, the British Caving Association says

About 70,000 people go on instructor-led courses into caves in the Yorkshire Dales every year, says Tim Allen, of the British Caving Association.

And large swathes of the UK's caves remain unexplored.

"It's the only true area of exploration which is possible for anybody," says Andy Sewell, who has 40 years of caving experience.

Mr Sewell estimates there are around 60 miles of caves "which we know are there but we haven't found".

On the safety of caving, he adds: "You need to be cautious. You have to have respect for the environment."

The ability to be calm, "keep you head" and not panic is important, says Mr Sewell, who belongs to the Westminster Speleological Group (speleology is the scientific study of caves).

Mr Sewell, here discovering a cave in Northern Ireland in 1996, hails the "amazing" feeling when you are one of the first humans to step into a cave

According to the US-based National Speleological Society,, external the most common causes of caving accidents include falling, being struck by falling objects and hypothermia.

But accidents are mostly due to poor judgement, little or no caving experience and falls, the NSS adds.

UK website New to Caving, external says some caves are very safe while others may present serious dangers.

The Thai boys became trapped after walking into the cave and being cut off by heavy rains, which flooded their way back out.

The international team that rescued them included caving experts and specialist cave divers. One of the rescuers, a Thai navy diver, died on the way out of the flooded cave.

In the UK, most cave divers, external have many years of "dry" caving experience before starting to dive. The two British cavers belong to the South and Mid Wales Cave Rescue Team, which is made up of cavers who have undergone specialist rescue and diving training.

Exeter University Speleological Society runs day and weekend trips, often to nearby caves in Devon

Mr Allen, of the British Caving Association, says "clearly caving is hazardous" - but that accidents are uncommon.

Mr Allen, who has helped discover large river caves in Papua New Guinea and an underground system in Borneo, says it has become safer over the years thanks to advances in weather forecasting and synthetic clothing to keep warm.

The 57-year-old, who has caved since he was a teenager and continues to go twice a week, has only ever been involved in two incidents.

In one, when he was flooded into a cave overnight after a "weather bomb" of rain, the local rescue team was called and the group managed to get out without any problems.

"Accidents still occur but often through bad luck and judgement but on the whole it's not a very dangerous sport," he says.

'Portal to another world'

Mark Fox, an instructor at the Peak District Survival School, says people are often anxious and fearful when he leads them into a cave for the first time.

"Obviously there's no natural light, they are afraid the light source might fail," he says

But the reward? "Going into a cave, it's like entering a portal to a different world," explains Mr Fox, who started caving 20 years ago.

Mark Fox, who started caving 20 years ago, says the thrill comes from "the opportunity to see things not many people have"

He recalls seeing the remains of skeletons of prehistoric sabre-toothed tigers, rhinoceroses and bears during a caving trip to Scotland.

"To think that's been there for 65-70 million years is quite hard to get your mind around," he enthuses.

Student Mr Morgan, who is originally from Abergavenny, said there is "something humbling about seeing the guts of the Earth... while battling the irrational fear that they could change in an instant and come crashing down on you".

Ari Cooper-Davis, 22, from Cumbria, says it can be "therapeutic", but adds: "That's not to say that it's peaceful though.

"There's a lot to think about; where am I going, how will I get back out from here, how long do we have left to explore, do I have enough batteries to last the trip, do I need to use any equipment to make it safe?"

"In caves that are new to you there's also a distinct sense of exploration and adventure; excitement about what might be around the next corner."

Ari Cooper-Davis, from Exeter University's caving club, says he was "a little bit scared" before trying caving for the first time

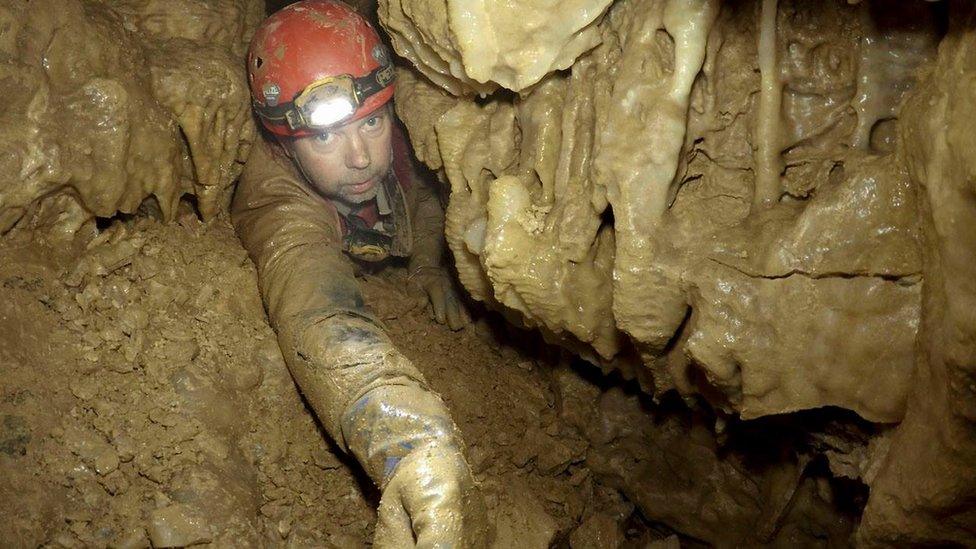

Chris Binding, a professional caver in the Mendip Hills in Somerset, describes caving as "the next best thing to being on another planet" and a "sensory overload".

"It's just like being in the reality of what you imagine as a child it is like to be in works of fiction with smugglers and dens."

But he insists that it is safer than most non-cavers tend to believe. "Really, it's not far dissimilar from going for a night-time mountain hike."

Chris Binding describes underground as "an unusual natural world" with "geology you don't normally see"

Mr Cooper-Davis admits that on paper, caving does not sound like much fun. "It's cold, and dark, and wet, and tiring. You get sore knees, bump your head on the roof, and have to crawl through thick mud.

"But together they make a varied and exciting adventure in a completely alien world. There are some magnificently beautiful things underground too, like chambers full of sparkling crystals, or spectacular waterfalls thundering down shafts of bright sunlight.

"We've got some of the best caves in Europe, here in the UK, and practically nobody even knows that they're there," he adds.

"Caves are one of the last true wildernesses in the UK, and you can really be someone exploring something new for the first time. It's a magical feeling."

- Published3 July 2018

- Published27 June 2018

- Published18 July 2018