What can we take from President Trump's UK visit?

- Published

This is how it works in Trump world. The US president arrives at a party, causes a fuss, breaks some crockery, and leaves everyone stunned.

Then as the dust settles, he declares what a good time he has had, how it's all been a great success, while offering a few words of apology for the disruption caused. So it was at the Nato summit, and so it was during his visit to Britain.

Mr Trump used his interview in the Sun to throw a few plates at Theresa May, criticising her Brexit strategy, threatening to block a trade deal with the US, praising Boris Johnson. Cue outrage and much gnashing of teeth.

Then came the news conference at Chequers where the president revealed he had apologised to the prime minister, praising Mrs May as an "incredible woman... doing a fantastic job... a terrific woman", insisting the UK-US relationship was "the highest level of special", all the while accepting that a trade deal might be possible just so long as there were no "restrictions" on US firms.

And so it goes: the UK-US relationship settles back on to an even keel and life returns to normal. That, at least, is the hope of British officials.

President Trump dined at Blenheim Palace, the birthplace of Sir Winston Churchill

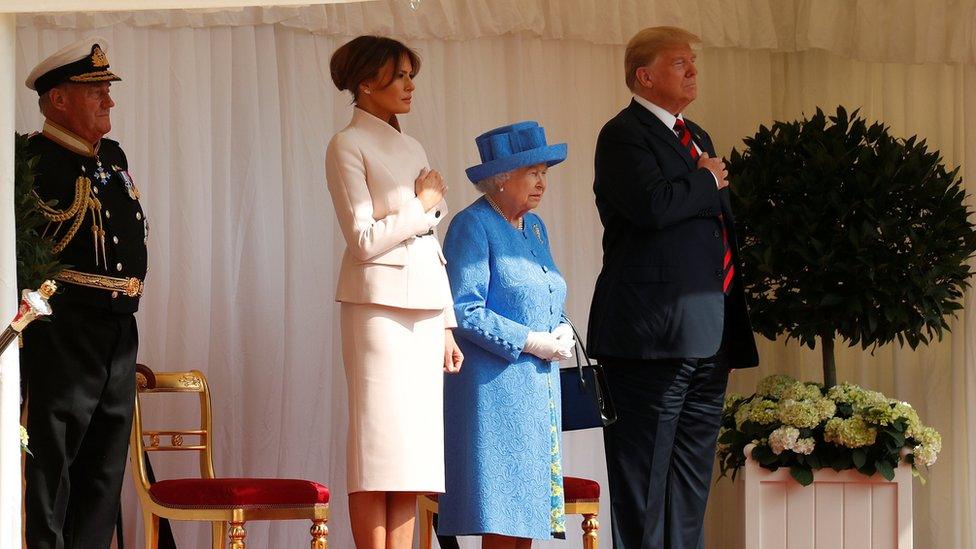

They designed this trip to show Mr Trump the depth of the relationship between the UK and the US: the history of Blenheim and Churchill, the dinner with business leaders who create jobs in America, the special forces who co-operate in the fight against terrorism, the Queen who has met 11 of Mr Trump's predecessors.

The symbolism was clear: the ties that bind Britain to the US are long and deep.

And government sources said the talks with Mr Trump at Chequers were good. They said the fallout from the Sun interview shaped the mood.

Any discussion that began with Donald J Trump apologising put the other side in a stronger position. The conversation, I am told, was relaxed, detailed and covered all the issues from the Middle East to North Korea. "It was good, solid, substantive stuff," said one source.

"We landed some messages." In other words, so they hope, the special relationship continues, Mr Trump's apology and recantation on trade enough to correct the damage of the interview in the Sun.

But is that really true? The president's words cannot be unspoken. He has described the UK as being in "turmoil", a "hotspot with lots of resignations".

He intervened directly in domestic UK politics, a gross breach of diplomatic etiquette. And even worse, he intervened in favour of the prime minister's opponents.

This was more than being undiplomatic to one's host: this was a hostile act that handed ammunition to those Brexiteers wishing to undermine the prime minister's Brexit strategy.

And what is more, the president was plain rude: to Mrs May whom he criticised for ignoring his advice.

And for good measure, Mr Trump said Britain was "losing its culture" because of immigration.

Until now, many British politicians tend to say things like "focus on what Donald Trump does, not what he says", "ignore the tweets, stick to the substance."

They also say the special relationship is about more than how well the Oval Office gets on with Number 10: the core of the relationship, they insist, is the military, security and intelligence nexus.

They like to quote Winston Churchill's speech in Fulton, Missouri in 1946 when he popularised the phrase "the special relationship" which he described as "not only the growing friendship and mutual understanding between our two vast but kindred systems of society, but the continuance of the intimate relationship between our military advisers".

Winston Churchill's 1946 speech at Fulton, Missouri, helped popularise the term "special relationship"

In her prepared statement at Chequers, the first point Theresa May made was to highlight the importance of UK-US military co-operation around the world.

My question is this: how long can this security relationship continue when the political tensions are so great?

How long is it before the policy differences between the Trump White House and the May Downing Street begin to infect the institutional relationships - the diplomats, the soldiers, the spies - that normally stay immune from the poison of day-to-day politics?

Can the two relationships really continue to exist in isolation?

Note this: since Donald Trump took office, Theresa May has had to disagree with him publicly over his decision to impose trade tariffs on EU steel, abandon the Iran nuclear deal, move the US embassy to Jerusalem, order a travel ban on Muslims from some countries and retweet anti-Muslim messages from a British far-right group.

Mr Trump has also questioned the multilateral, liberal rules-based order that Britain defends, while embracing the regimes of authoritarian "strong men".

President Trump's visit has prompted big public demonstrations

Mr Trump wants to approach the world not through alliances but individual bilateral deals, a series of transactional relationships with other countries that balance short-term national interests.

In his mind, the UK may be just another country with which to deal. But at Chequers, Mrs May deliberately warned Mr Trump not only that it was their responsibility to ensure the transatlantic relationship endured, but also that it was based on the shared values of democracy and justice.

So there are two fundamentally opposed positions: Donald Trump's belief in an interest-based transactional relationship with the UK, where access to US markets is determined by how detached the UK is from EU markets, and Theresa May's view of a transatlantic relationship based on shared values.

And the question remains: as the US and the UK drift further apart between these positions, how long can the institutional relationship between the soldiers and the spies survive the tensions of their political masters?