Brexit: How would a second EU referendum be held?

- Published

A former Conservative cabinet minister has called for a second Brexit referendum. Writing in the Times, Justine Greening, who used to be education secretary, argued that another vote would be "the only way to end deadlock".

But how, in practice, could a second vote happen?

Parliamentary approval

The government has ruled out a new Brexit referendum and the Labour party says it's unlikely - although its Shadow Brexit Secretary, Sir Keir Starmer, says it is sensible to keep "all our options on the table" - in the event of Parliament voting down a Brexit deal or in the case of a "no deal" scenario.

Downing Street said, in response to Ms Greening, that a referendum will not happen "in any circumstances".

So unless there is a dramatic change in party policy, it's highly unlikely a referendum would be called in the first place.

That's because a referendum requires an Act of Parliament, which needs to be voted through by the majority of MPs.

And while there are vocal supporters on all sides, currently there are not enough MPs who support the idea of a second referendum.

Timing

Even if MPs and peers agreed in principle to hold a second referendum, the legislative process can be drawn out.

Parliament would need to pass detailed rules for the conduct of the poll and the regulation of campaigners.

It took seven months, external before Parliament signed off the previous referendum legislation in 2015. Further time was also needed to pass secondary legislation on areas such as voting registration.

In theory, Parliament could copy over some of the legislation from the 2015 Act in order to try to speed the process up.

But according to David Jeffery, a politics lecturer at Liverpool University, this might not save a lot of time because issues would still need to be debated and scrutinised by MPs and Lords.

Aside from the time to pass the legislation, there's also the length of the campaign to consider.

Last time around there was a four-month period between the then Prime Minister David Cameron announcing the referendum in February 2016, and the vote taking place on 23 June.

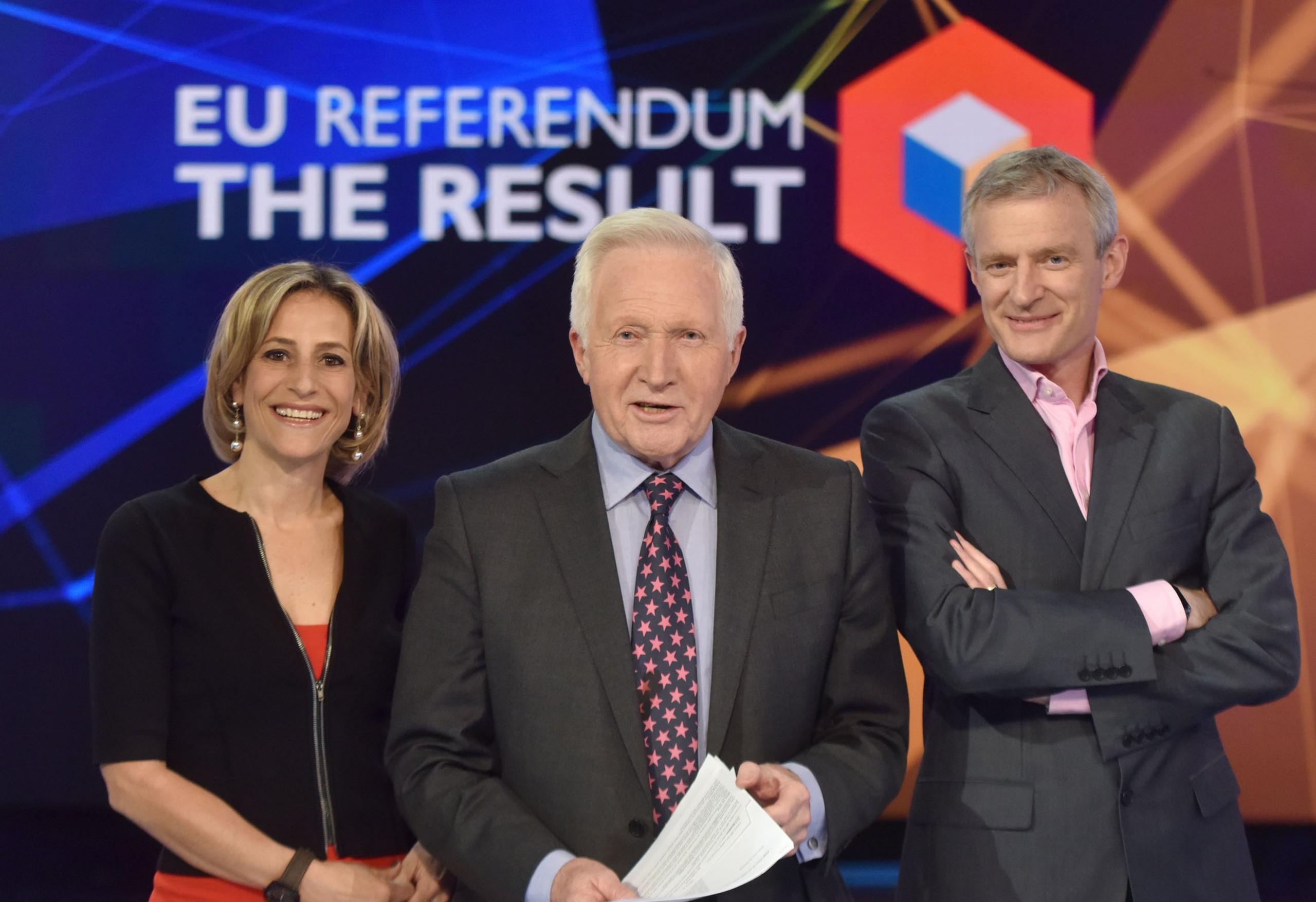

Justine Greening claims a new Brexit referendum would "end deadlock"

Furthermore, the Electoral Commission has recommended, external that in future there should be at least a six-month gap between legislation being passed and a referendum being held.

That's to allow enough time to register campaigns, put counting officers in place and give people information on how to vote.

So combining the time to pass the legislation and allowing for a campaign, it might not be possible to hold a second referendum before the UK is scheduled to leave the EU in March 2019 (i.e. when the Article 50 process is due to expire).

And holding a referendum after the Article 50 process could cause a number of practical problems.

For one, what if the country voted to remain in the EU, but had already left by the time the vote was held?

This could be avoided if the EU agreed to extend the Article 50 deadline - but this would need to be unanimously agreed by all EU member states.

The question

There's also the referendum question itself and the options on the ballot paper to consider.

These need to be presented "clearly, simply and neutrally", according to the Electoral Commission.

Justine Greening argues for three options: accept a negotiated Brexit deal, stay in the EU, or leave with no deal.

David Jeffery says having more than a yes/no option could complicate the process:

"With three options you could have a situation where just 34% decide the winning option.

"And that leads to questions about the type of voting system you want - like choosing the options by preference order," he says.

"But then you need to ask 'do the public understand the system and how might it work in such a short period of time?'"

In the end it would be up to the Electoral Commission to assess that question.