Brexit: What would 'no deal' mean for food and medicine?

- Published

The government has been urged to speed up the publication of its guidance for a 'no deal' Brexit, after a survey of 800 businesses by the Institute of Directors found that fewer than a third of them have carried out any Brexit contingency planning.

Recently, the Brexit debate has been dominated by the potential implications of the UK leaving the EU without any kind of deal in place next March.

Some of the details have been pretty alarming, but the whole point about contingency planning is that it has to take account of the worst-case scenario.

So what could 'no deal' mean for two essentials of daily life - food and medicines?

Food

The UK produces roughly 60% of the food it consumes. Of the remaining 40%, about three-quarters is imported directly from the European Union, including a lot of fresh fruit and vegetables like citrus fruits, grapes and lettuces.

In other words, the food industry is highly dependent on just-in-time supply chains, and while the UK has more supermarkets per head than anywhere else in the world, those supermarkets keep very little in stock. It all comes in overnight, much of it through Dover.

That is why the idea of gridlock at UK borders - in the event of a 'no deal' Brexit - is such a worry.

Strike action which closed the port of Calais in 2015 led to queues of lorries on the M20 in Kent stretching back for 30 miles. The logistics industry, and Dover District Council, fear that the disruption caused by a 'no deal' Brexit could last for far longer.

"If there were to be no deal there would be many, many months of disruption to existing choices," said Ian Wright, of the Food and Drink Federation, "frankly until some kind of deal was reached."

So what has the government said?

Not a lot in public, and pressure on the government from supporters of Brexit to highlight 'no deal' planning (as a means of putting pressure on the European Union) has now been replaced by accusations that their opponents are selectively leaking scare stories.

The government is planning to publish, in two tranches in late August and early September, about 70 technical notices on how businesses and consumers should prepare for no deal. I understand that about 20 of them will impact directly on the food industry.

Lettuces are extremely sensitive to any disruption in the supply chain

Brexit Secretary Dominic Raab was reluctant to give MPs many details when he appeared before the Exiting the EU Select Committee, insisting that he wanted to wait until he could "set it out in a responsible and full fashion".

But when Mr Raab was asked directly if the government was considering stockpiling food, he said: "It would be wrong to describe it as the government doing the stockpiling.

"Of course, the idea that we only get food imports into this country from one continent is not appropriate, but we will look at this issue in the round and make sure that there is adequate food supply."

The implication that it was businesses rather than the government that should be doing any stockpiling has not gone down well within the food industry.

"If they are expecting the industry to be stockpiling things, they will be in for a surprise," said one executive working for a major supermarket chain.

"It's nonsense. There is absolutely no capacity in the UK supply chain for extra food to just sit around."

For one thing, you cannot stockpile perishable food. That's obvious. And a huge amount of fresh produce arrives from the EU on a daily basis.

"The problem is the government doesn't appreciate what that means in practice," said Andrew Opie, of the British Retail Consortium (BRC).

"For example, in the run-up to last Christmas 130 lorry-loads of citrus fruit came through Dover from Spain every single day. That's the sort of volumes we're talking."

The BRC estimates that, on average, more than 50,000 tonnes of food passes through British ports every single day from the EU.

Stockpiling is simply not an option for many food retailers

So border delays, caused by sudden customs and regulatory checks, could very quickly lead the distribution system to break down. For fresh produce that could mean shorter shelf lives, and rising costs in the system.

Industry sources say the government has suggested that it would keep regulatory checks at borders to a minimum in the event of no deal, in an effort to keep traffic moving. But that wouldn't help much if robust checks were being carried out on the EU side.

"If there were big border hold-ups, after three days there would be gaps on the shelves in fairly short order," said Chris Sturman, chief executive of the Food Storage and Distribution Federation (FSDF).

What about chilled or frozen food?

The trouble is there is very little spare storage capacity. According to the FSDF, there are 385 refrigerated warehouses around the country, but more than 90% of refrigerated warehousing is in constant use and margins are extremely tight.

Supermarkets are certainly making contingency plans. But rather than involving stockpiling food, which one executive described as a "non-starter", they revolve around how they might be able to source produce from other countries if European supply chains are seriously disrupted.

They have done that before. For example, bad weather in Spain last year meant lettuces were temporarily imported by air (and therefore more expensively) from Latin America, and supplies were rationed. The 2015 industrial action in Calais also promoted retailers to diversify their supply chains.

But these are short-term fixes and at the moment the whole industry is trying to plan for an outcome that is impossible to predict.

"We're not going to run out of food if there is no deal," said Ian Wright from the FDF. "There is a way to increase capacity, to grow more of particular vegetables, to cut out the waste that occurs at the moment.

"But the short-term disruption could be severe. The government needs to understand that."

A spokesperson for the Department for Exiting the European Union said the government was preparing for all eventualities but had no plans to stockpile food.

"The government has well-established ways of working with the food industry to prevent disruption - and we will be using these to support preparations for leaving the EU. Consumers will continue to have access to a range of different products."

Medicines

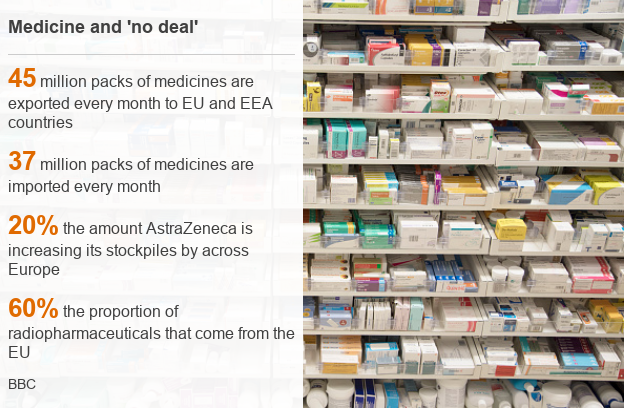

Another big issue is medicines. Every month the UK exports 45 million packs of medicines to the EU and EEA countries, and imports more than 37 million. Again, prolonged disruption at borders could threaten supplies of drugs and other vital healthcare products - both in the UK and elsewhere in Europe.

There is more scope with medicines than with food to increase stocks of things like tablets, but other imported drugs such as insulin often need to be refrigerated and may therefore pose bigger logistical challenges.

So what has the government said?

Health Secretary Matt Hancock told the House of Commons Health Select Committee recently that "we are working with industry to prepare for the potential need for stockpiling in the event of a 'no-deal' Brexit".

"This includes the chain of medical supplies," he said, "vaccines, medical devices, clinical consumables and blood products."

Industry sources confirm that they are in close contact with the government to make sure it understands their plans, and that it knows what the practical implications of leaving without a deal could be.

The UK-based pharmaceutical company AstraZeneca told the BBC on 17 July that "as a safety net" it was increasing its drugs stockpiles across Europe by about 20% in preparation for a no-deal Brexit.

AstraZeneca's chief executive, Pascal Soriot, has subsequently said the company is doing everything it can to be prepared, and to make sure patients do not run out of their medicines.

"We typically run about three months of inventory for our medicines," he said. "We are increasing this by one month so that we have additional inventory to protect against a disorderly Brexit, if you will."

The company is not increasing its global stock, but it is locating more of it in the UK and Europe to be available if necessary.

Two other big companies, France's Sanofi and Switzerland's Novartis, have also confirmed plans to increase stockpiles.

But I understand that the other big UK-based pharmaceutical company, GlaxoSmithKline, has decided for the moment not to increase the additional stocks of drugs that it holds in the UK.

GSK was not able to say why it has taken such a decision, citing commercial confidentiality.

The focus of its stocks is mostly on medicines that are not necessarily readily available from competitors or generic alternatives.

GSK is certainly preparing for Brexit though. It has already started the process of moving the EU-wide marketing authorisation for more than 1,000 drugs registered in the UK to other EU countries, mostly to Germany.

And GSK's annual report released in March 2018 reveals that the company is spending £70m in one-off costs connected to Brexit, with additional ongoing costs of up to £50m per year depending on what arrangements are made in the future.

The UK imports more than 37 million packets of medicines each month

But perhaps the biggest challenge in the health sector is faced by those who rely on products which are only of medical use for a few days or sometimes a few hours.

In particular, this means radio isotopes that are essential for things like cancer scans.

"A 'no deal' scenario will be difficult for the nuclear medicine community," said John Buscombe, of the British Nuclear Medicine Society. "We calculate that 60% of the radiopharmaceuticals we use come from the EU, affecting as many as 600,000 patients per year."

At the moment they arrive by road and rail across the Channel.

"If they arrive too late," Mr Buscombe said, "they may not be useable because they will have decayed too much.

"They could be flown in, but that will result in increased costs that the NHS will have to pay."

When asked about the supply of medical radio isotopes by the Health Select Committee, Mr Hancock said: "We are working with industry to ensure that exactly that sort of medicine, or rather diagnostic need, is taken care of… it is incredibly important for me, as Secretary of State, to ensure that people will have access to the medicines they need."

- Published17 July 2018