EU migration: How has it changed the UK?

- Published

When almost 17.5 million people voted for Brexit, concerns about immigration were at the forefront of many of their minds. As the referendum campaign kicked off, official statistics revealed near-record levels of net migration, undermining David Cameron's attempts to show that his policies to control it were working.

But despite almost everyone having a view about EU migration, the evidence for how it really affects the UK was thin on the ground.

A chunky report by the Migration Advisory Committee, an independent public body that advises the government, is a serious attempt to try to explain all the effects of European Economic Area (EEA) immigration.

So let's go through the key facts.

1. The UK has undeniably become more European

There's no disputing this one.

The UK has seen more people arriving to live here than leave for other shores and the population has been rising for two decades.

Going back to the late 1990s, although freedom of movement was already in place, there wasn't substantial concern about EU migration.

Things changed when eastern and central European nations joined in 2004 and the UK (unlike Germany and others) chose not to exercise a seven-year block on workers from these poorer countries accessing the UK's labour market.

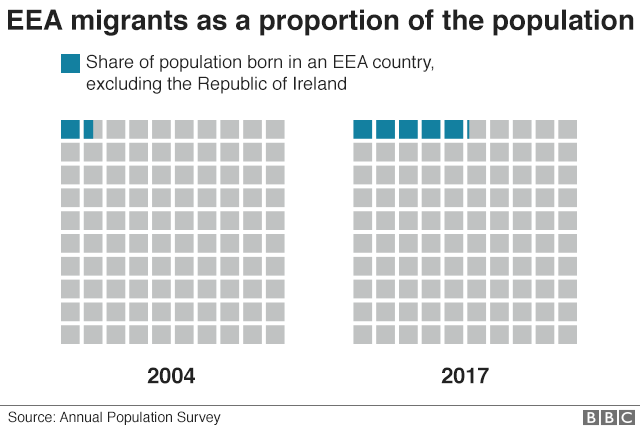

And the rest is history. Between 2004 and 2017, the share of the population who were from an EEA country rose from 1.5% to just over 5%.

But things are changing again.

The number of EU citizens moving to the UK has decreased since the Brexit vote.

Workers from the east now earn more at home than before. In 2004, the British pound bought more than seven Polish Zlotys, external, while now it is less than five.

So for potential eastern European migrants, moving to Britain looks less and less attractive.

2. EEA migrants tend to have more skills than British workers

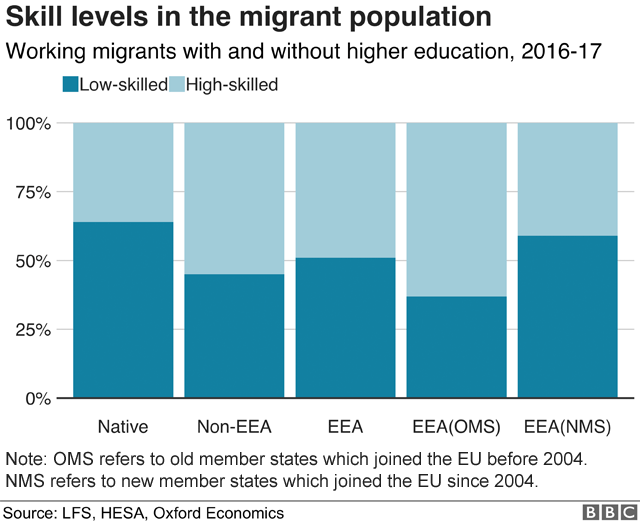

This stands to reason - the most skilled are the most likely to have the get-up-and-go to move countries - and that's been seen in economic migration the world over.

But that average figure masks a more complex picture.

The most highly skilled EEA migrants to the UK are likely to be from the "old member states" - including the original founding nations such as France, Germany and Italy.

The figures also show that workers from the "new member states" are better qualified than their British peers. But they're not always using those skills to maximise how much they can earn in the UK.

3. There's a big difference in how much European workers earn (*national average)

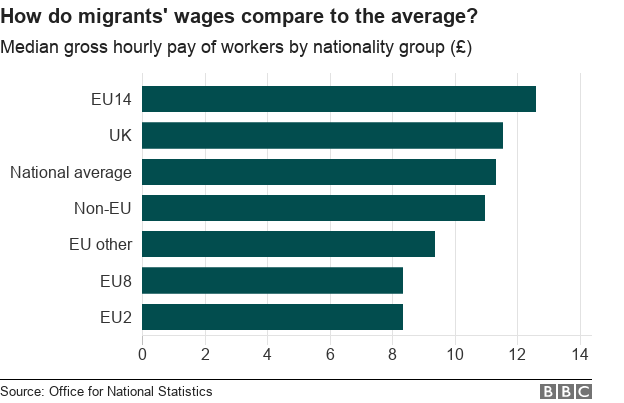

If you look at the range of hourly rates paid to European workers, those from the east are likely to earn less than those from the old member states.

They also tend to be in jobs earning less than British workers.

In the early days of eastern European migration, there were no end of anecdotal stories of highly qualified people coming to the UK to do very basic jobs because they could earn so much more than at home.

But the all-important question is what effect does this have on the national coffers?

4. EEA workers are paying more in tax than they are taking out in benefits

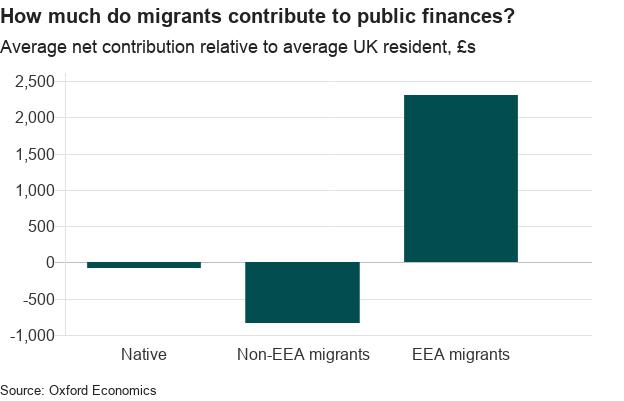

Figures calculated for the Migration Advisory Committee show that the average adult migrant from the EEA contributes £2,300 more to the UK public purse than the average UK resident.

Old member state citizens contribute the most - but even the lower-paid eastern European workers are making a net public contribution. In all, say the MAC, EEA migrants paid £4.7bn more in taxes than they took out in benefits and public services.

It's a big number - but the MAC says it's small beer. Averaged out over the whole of the UK-born population, it amounts to an extra £1.70 a week, per person.

5. Migration can lead to new jobs - rather than competition for existing ones

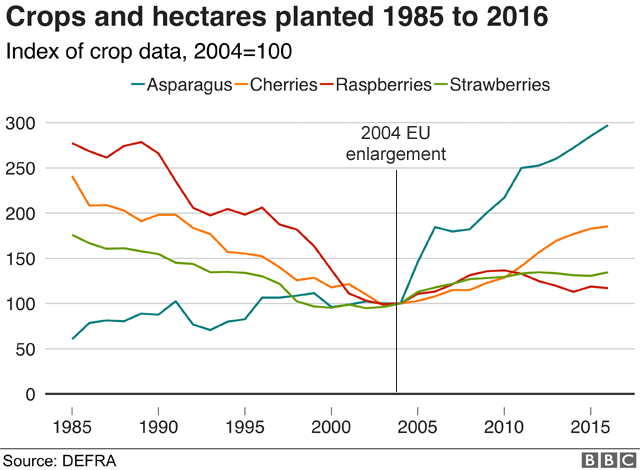

Take one example, in the agriculture sector: the graph clearly shows that there had been a long-term decline in British production of asparagus, cherries, raspberries and strawberries. But all four crops have grown or stabilised since 2004 when new workers from the east became available.

Farmers, quite simply, saw an opportunity to expand thanks to a massive supply of cheap labour they didn't have before. They say that British workers, by and large, don't want the jobs, with long hours and not-so-fantastic pay.

What's not remotely clear is how employers would respond if the ready supply of EEA labour dried up, should free movement end.

Critics of the current system say they would inevitably have to offer better terms and conditions to existing workers in the UK and invest more in productivity and technology - think strawberry-picking machine, rather than strawberry picker. That, say critics of free movement, would be a good thing for the UK.

And that brings us to the other big topic - is the disruption caused by mass migration affecting the UK in other ways?

6. There's no evidence that EEA migrants are draining public services.

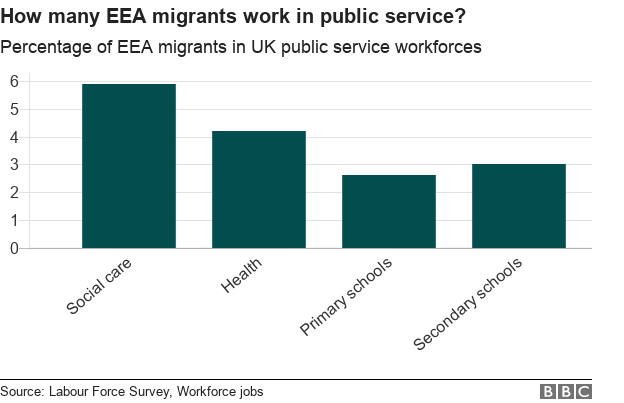

The MAC report looked at a number of key public services - starting with health - and found EEA migrants contribute more to the NHS and social care than they use.

EEA workers make up an increasing share of the workforce in this sector, although historically the UK has relied more on nurses and doctors born in Commonwealth countries.

The NHS doesn't record the country of birth of patients. So the report used the fact that EEA migrants to the UK tend to be younger - and we know that more is spent on caring for elderly than young people - to conclude that they're contributing more through their taxes than they are taking out.

The MAC did find an effect in both private and social housing, though.

Its analysis suggests that migration has increased house prices and added to the demand for social housing, "inevitably at the expense" of others.

Although migrants are a small fraction of people in social housing, they are a rising number.

However, the report concludes that the reduction in stock - because too few homes for social rent are being built - has a part to play too.

And it adds that the impact of migration on house prices cannot be seen "in isolation from other government policies".

All of which leaves one final question: what has been the effect on communities?

7. It's hard to measure the impact of migration on communities

The MAC says this is the hardest question to answer. Anecdotally, people are concerned about change - and the committee says ministers need to do more to monitor and manage how migration affects local communities.

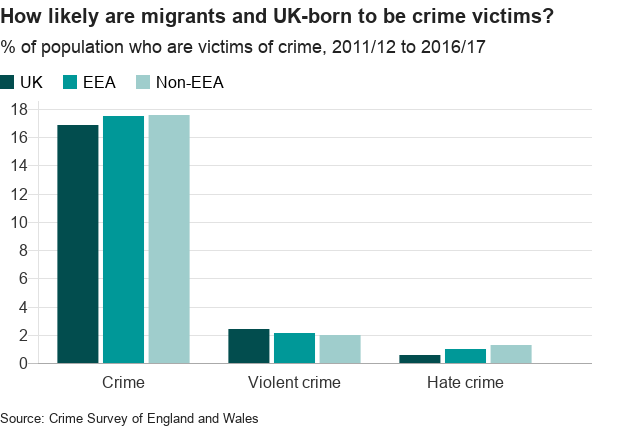

But it also said it found no evidence that migration had damaged communities through crime.

Citizens of new member states were more likely to receive a caution or conviction, than UK-born people, but there are also disproportionately more younger men among migrant workers - and young men of any background are the most likely to break the law.

The MAC found no evidence that migration, despite all the apparent concern, had damaged people's sense of belonging.

Two academic studies, the British Household Panel Survey and the UK Household Longitudinal study found that people like their neighbourhoods more now than ever.

The government's own annual study of how involved people are in their community has found no alarm bells ringing because of increased migration. However, some critics say the pace of change to the character of some communities, brought on by migration, can't be fully measured by these nationwide studies.