Westminster attack: The issues raised at the inquests

- Published

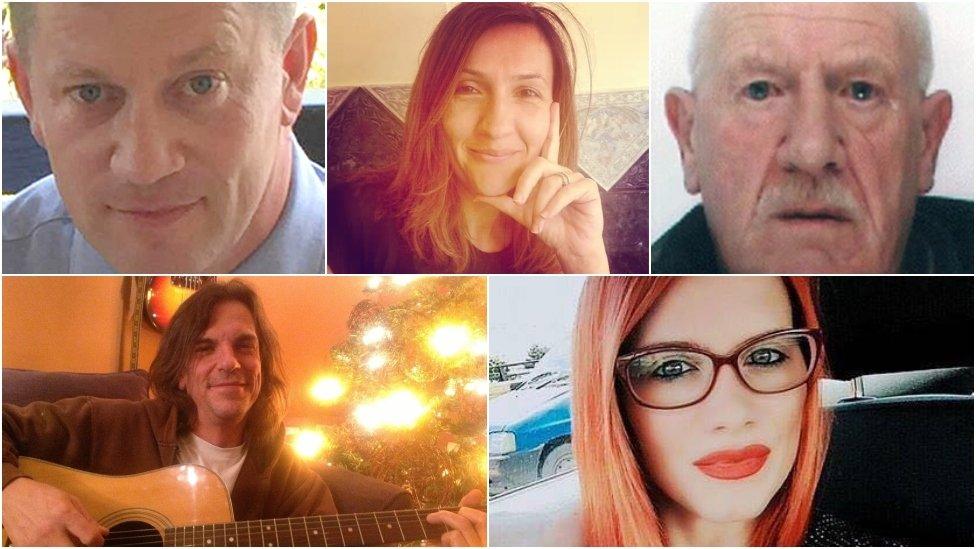

Clockwise from top left: PC Keith Palmer, Aysha Frade, Leslie Rhodes, Andreea Cristea and Kurt Cochran all lost their lives

The Westminster terror attack of 22 March 2017 resulted in the greatest loss of life in a UK terrorist incident since the 7/7 bombings 12 years earlier.

Over the past month, inquests have been taking place for the five victims of attacker Khalid Masood, who drove into people on Westminster Bridge before stabbing a policeman.

PC Keith Palmer, Aysha Frade, Leslie Rhodes, Andreea Cristea and Kurt Cochran all lost their lives.

During the inquests, several issues emerged, including armed policing at Parliament, security on the bridge and what the security service MI5 knew about Masood prior to his attack.

1. Armed policing

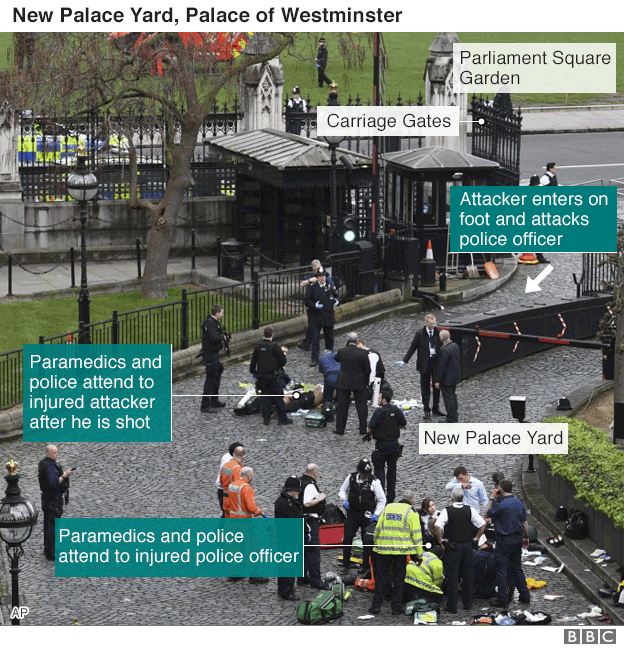

The "inadequacies of the security arrangements at the Palace of Westminster have been laid bare", the court was told by Dominic Adamson, representing the widow of PC Palmer, who was stabbed to death by Masood while guarding Parliament's Carriage Gates.

Masood was stopped after an armed close protection officer, in the area by chance, confronted him and then shot him dead.

At the time of the attack, two armed officers - PC Lee Ashby and PC Nicholas Sanders - were on duty in New Palace Yard, the "secure" courtyard area between the gates and the members' entrance to Parliament.

The pair had been near the members' entrance, which was busy that day because of Prime Minister's Questions, and then moved towards an area close to where Masood had crashed his vehicle rather than to the gates.

However, CCTV showed the officers had been away from Carriage Gates for almost an hour when Masood attacked.

The officers said their positioning on the day was in line with regular instructions they received on the ground and that their patrol was an unpredictable "roving" one around the courtyard, which meant often being away from the gates when they were open.

Both said they and other armed officers had not been told to patrol in any other way.

However, official instructions for the post, shown to the inquests, said armed officers should be "positioned in close proximity to the gates when they are open".

The inquests heard the Carriage Gates, which were old and hard to manoeuvre, were typically kept open throughout the day.

An official assessment found the gates to be vulnerable and that uniformed officers like PC Palmer, who were in direct contact with the public, needed armed support stationed behind them when the gates were open.

PC Ashby and PC Sanders said they were unaware of these instructions.

Senior Met figures said they were surprised by what had been said by the two officers.

Chief Supt Nick Aldworth said the officers "should have been" at the gates that day.

But senior police witnesses provided different accounts of how strictly the official instructions needed to be followed.

Inspector Stuart Rose, who supervised armed officers at the Palace of Westminster, told the inquests they were open to some interpretation.

But Commander Adrian Usher, who leads the Met's protection command, said: "There is no flexibility in the interpretation of post instructions."

Questions were also asked about how many officers had accessed instructions for patrolling the area in the months before the attack.

PC Keith Palmer was pronounced dead at 15:15 on the day of the attack

The court heard there was no evidence that PC Sanders had accessed the internal system containing the instructions, while PC Ashby had last done so in mid-2015.

An internal inquiry concluded that the failure to adhere to official instructions was "not unique to these officers, and that wider command practice was reflective of the same misunderstanding".

Commander Adrian Usher said 83% of armed officers had "recently" accessed the system prior to the attack.

But when he was called back to court, the claim was revealed to be false and documents showed only 13% had accessed the system between December 2015 and July 2016.

Mr Adamson submitted there was "no effective system" for ensuring that armed officers complied with official instructions and argued the Met had sought to "traduce" PC Ashby rather than "investigate fully and take responsibility for its own failings".

Susannah Stevens, representing PC Palmer's parents and sisters, suggested that the police constables were being "hung out to dry" by senior officers in order to conceal broader "systemic failures."

2. Security on the bridge

Four of the victims - Kurt Cochran, Leslie Rhodes, Aysha Frade and Andreea Cristea - were murdered after Masood's vehicle mounted the pavement on the bridge and deliberately drove into pedestrians.

The inquests heard that no official consideration had been given to placing barriers on Westminster Bridge prior to the attack - or for some weeks after it.

Work to erect the current barriers began 73 days later on 3 June 2017 - the day after the London Bridge terror attack.

Lawyers for the victims' families said that, in light of the Nice and Berlin vehicle attacks in 2016, the authorities should have taken measures to protect pedestrians in such a sensitive location.

The court was told that Westminster Bridge had not been officially defined as a "crowded place" - the Home Office classification of places or events requiring greater security for pedestrians.

Four victims died after being struck on Westminster Bridge, many more were injured

Chief Supt Nick Aldworth said Westminster Bridge was not "seen as a location that we needed to erect barriers on".

He said counter terrorism officials were there to advise, but the "responsibility for protection rests" with the owners or users of locations.

Siwan Hayward, a senior official at Transport for London, which was responsible for Westminster Bridge, said it had received "no advice, guidance or input from the police or any of the wider Home Office or security services to suggest that there was a risk to the bridge".

She said "no-one was engaging systematically with us about vulnerable locations".

3. Masood and MI5

The inquests heard MI5 had closed its file on Masood in 2012 after judging he was not of national security significance.

A senior official - referred to as Witness L - gave evidence anonymously and said decision-making in relation to Masood was "sound" given the information available to investigators, which never included intelligence about attack planning.

Witness L said MI5 monitors 3,000 of subjects of interest and it would not have been proportionate to devote resources to someone fitting Masood's profile.

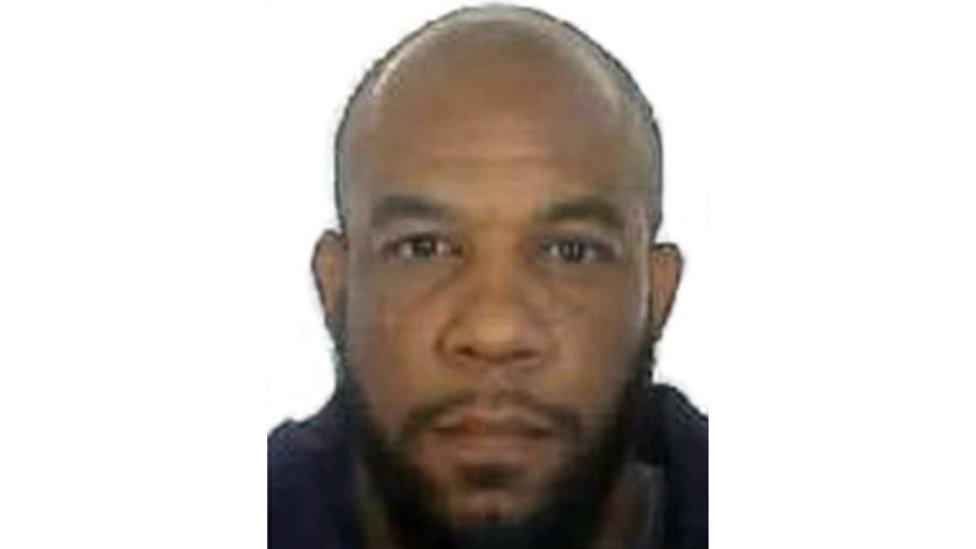

Khalid Masood was shot dead outside Parliament

Masood, instead, fell into the 20,000 former subjects of interest, meaning people who have previously been investigated before being discounted as a threat.

Salman Abedi, the Manchester Arena bomber, was also in this category. In contrast, the leader of the London Bridge attackers - Khuram Butt - was a live subject of interest.

Witness L said Masood had engaged in very limited attack planning and acted entirely alone, meaning there was no real opportunity to stop him.

In summary, MI5 knew the following about Masood at the following times:

In 2004, a mobile number for Masood was found within the phone of Waheed Mahmood, an al-Qaeda fanatic who was a prime mover in what was then the UK's biggest bomb plot.

From 2004-2009 contact details for Masood appeared several times during a series of MI5 investigations into one of his longstanding associates, whom Witness L refused to name in court. The details included Masood's then home address, more than one email address, and more than one phone number.

In 2010, MI5 received intelligence that Masood, then temporarily based in Saudi Arabia, was an extremist. MI5 opened a file on Masood and investigated the possibility that he was a Saudi-based facilitator for a group of men who were seeking to travel to Pakistan from the UK for terrorist training. This was ruled out after the genuine facilitator was identified. In December 2010, a decision was taken to close MI5's active investigations into Masood.

From 2010-2012 Masood appeared as an associate of people who were being actively investigated by MI5.

In 2012, Masood was formally downgraded to a former subject of interest. It is unclear why there was such a long delay in closing the file.

From 2012-2016 Masood appeared as an associate of members of the banned terrorist group Al Muhajiroun, which has been linked numerous terror attacks and plots. During the same period, the service had information that Masood was consuming extremist material and, in 2013, it received specific intelligence he had expressed satisfaction that the 9/11 terror attacks attracted some people to Islam.

Lawyers for the victims' families argued that the investigation into Masood should have been reopened given the accumulation of intelligence about him.

They also argued that Masood's propensity for violence - he had a string of convictions and was once charged with attempted murder - meant the service should have looked at him again after the advent of the Islamic State group and its calls for knife and vehicle attacks by lone actors.